See Wikipedia to distinguish between Biblia pauperum and the Poor Man's Bible.

Examples from the Internet Biblia Pauperum:

From The Warburg Institute Iconographic Database:

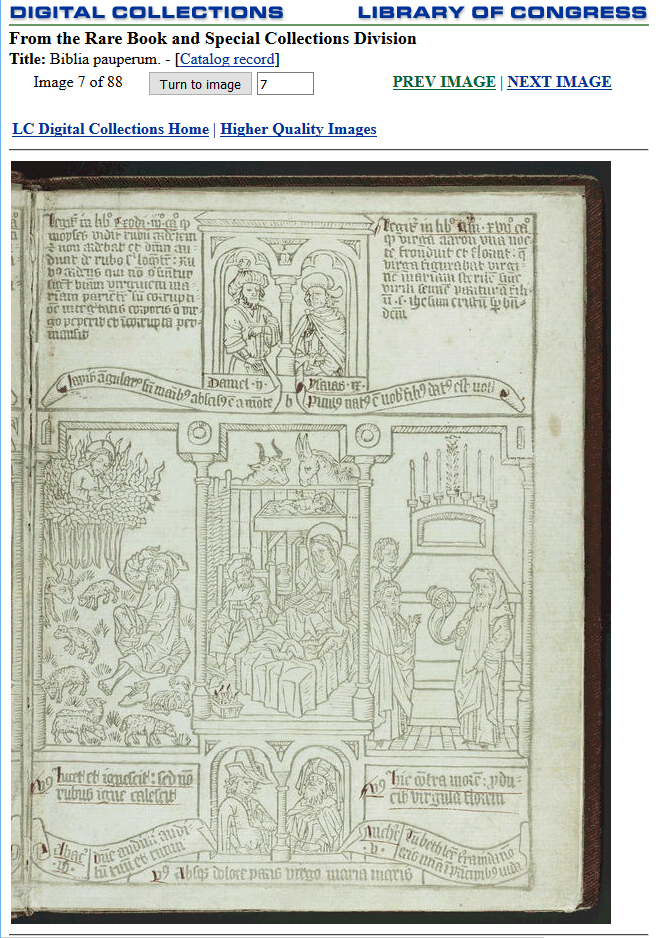

From the Library of Congress:

Final from a history of graphic design site:

[quote]

Biblia Pauperum

Technically, the Biblia Pauperum is a xylographic book, a blockbook whose pictures and text were produced by impressions from wooden blocks carved in relief. In fact, the paper was pressed onto the blocks after their carved surfaces, facing upward, had been moistened with dye. Though manuscripts of the Biblia Pauperum circulated in the Middle Ages, the blockbook editions, begun in the Netherlands where the art of woodcutting flourished, tended to proliferate between 1460-1490. In this period, the blockbook was a transitional form of publication between the production of manuscripts by hand and the printing of books by movable type. Most of the blockbooks in the fifteenth century, such as the Speculum Humanae Salvationis (Mirror of Human Salvation) and Ars Moriendi (Art of Dying), are religious in nature, but only the Biblia Pauperum is entirely Biblical in content.

Despite the popularity of the Biblia Pauperum, the origin and use of the blockbook, as well as the source of its title, particularly the appellation "poor man," are matters of conjecture. Perhaps the book was designed by friars and other clergymen who sought to educate the poor and illiterate folk in the unity of Scripture. Not only was the audience for such instruction certainly poor, but also the clergymen whose preaching was aided by the Biblia Pauperum were often mendicants or "poor men." Furthermore, the preaching and instruction influenced by the Biblia Pauperum may have been directed against one or more of the numerous heresies that were revived in the late Middle Ages. As a resource or reference work to combat heresy, the Biblia Pauperum affirms doctrinal orthodoxy, concerning the Trinity, the virgin birth of Jesus, the two natures of Jesus, his Resurrection, the Second Coming and Final Judgment, the damnation of the wicked, the salvation of the sanctified and their union with God in Heaven. To affirm doctrine, the Biblia Pauperum uses visual depictions, Biblical proof-texts, and interpretive commentary. Another use of the Biblia Pauperum may have been to assist in the conversion of the Jews. If anti-Judaism was characteristic of some segments of the medieval Church and society, other segments, overtly or covertly, sought to win the Jews to Christianity. Doing so was more expeditiously accomplished when the Jewish Old Testament was reconciled with the Christian New Testament.

Not to be discounted is the view that the Biblia Pauperum was reproduced rapidly and inexpensively because of the entrepreneurial instinct of printers and booksellers who found a market for their products. Because it was easily produced from engraved blocks, the Biblia Pauperum may have been the popular (or "poor man’s") counterpart of the illuminated manuscript. A single set of blocks was used indefinitely and even transported from one country to another, so that reproduction proliferated. Complicating the bibliographic history are numerous factors, some of which will be recounted below. When, for instance, blocks became chipped or cracked, replacements were carved. If in such cases an engraver intended to recreate the same images, there were still inevitable variations, though slight. More conspicuous variations resulted when an engraver used these opportunities for deliberate alteration, substituting one Biblical personage for another, adding or eliminating personages, or rearranging visual details. As a result, some of the printed images of the next impression were different. When, moreover, a copy of the book, rather than a set of blocks, was available, an engraver would use the printed images as models from which to carve blocks. His newly created blocks would then print pictures closely resembling though different from his models. Finally, the more popular forty-leaf blockbook is inevitably compared with the later fifty-leaf edition, fewer copies of which are extant. Both editions are essentially the same, the longer one having ten more pages interspersed through the shorter prototype, rather than added on at the beginning or the end.

The design of each leaf is both horizontal and vertical. The central horizontal arrangement is that of an iconographic triptych in which the three panels call attention to interrelationships of the Old and New Testaments. The panel in the middle is a scene from the New Testament, and the panels at the sides usually depict episodes from the Old Testament, though there are two notable exceptions: the left-hand panel of the twentieth triptych (v) depicts the five foolish virgins of Matthew 25:3, and the right-hand panel of the fortieth triptych (.v.) shows St. John and the angel from Revelation 21:9. The central vertical arrangement involves an upper scene of two prophets or patriarchs, each framed by an arch. A pillar separates the two figures, whose names are inscribed immediately below their busts. Each prophet or patriarch holds the end of a scroll bearing a verse from the Old Testament, a verse related typologically to the subject from the New Testament in the middle panel below. In the spaces alongside the figures are other passages from the Old Testament, usually paraphrases and interpretive commentary. The lowest scene in the vertical arrangement resembles the uppermost scene, though there are some differences. In the lowest scene the names of the Old Testament personages are inscribed on the scrolls with the scriptural passages. In the smaller spaces alongside the figures and below them are brief verses of interpretive commentary. By its interlocking horizontal and vertical design, crosslike in appearance, each leaf calls attention to the New Testament scene of the middle panel. This focus is reinforced by the positions of the four Old Testament personages, two above and two below the New Testament panel of each leaf. The personages, who become virtual witnesses of the fulfillment of their prophecies or of the episodes in which they participated, thus escape the temporal limitations of their own lives, develop a Christ-centered view of history, and acquire insight into the enigmas of the Old Testament.

The design of three panels and four figures on each leaf of the blockbook may be numerologically significant, for the sum and product, respectively seven and twelve, of the two numbers have mystical significance. Forty, the total number of triptychs, has various meanings, including the days in which Noah and his family were protected from the Deluge, the years that the Chosen People wandered in the wilderness, the days across which the Lord was tempted in the desert and the days that the risen Christ remained on earth before his Ascension.

The sequence of middle panels in the blockbook draws attention to Christ’s unfolding ministry of redemption and the offer of salvation to humankind. The first triptych depicts the Annunciation, after which Christ’s birth, infancy, childhood, and adulthood are depicted in the middle panels. The Passion, Death, and Resurrection of Christ — the events of the Paschal Mystery — are featured in almost a dozen triptychs. Doomsday is pictured in the middle panel of a later triptych, and the blockbook ends with the fortieth triptych, the middle panel of which is the crowning of the sanctified soul in Heaven, the reward of eternal bliss.

While the interaction of textual and visual elements is significant in the Biblia Pauperum, the separate consideration of these components is instructive. As a text, the Biblia Pauperum is a brief compendium of harmonies and concordances among Biblical texts and a guide to interpretations thereof. By its citation, juxtaposition, and interpretation of Biblical passages, the blockbook epitomizes the technique of medieval commentary compiled in monumental works such as the Glossa Ordinaria of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries and the Catena Aurea by St. Thomas Aquinas. Despite its relative brevity, the blockbook provides a frame of reference for understanding Biblical allusions in religious writing, including sermons, hymns, penitential literature, and devotional poetry as late as the seventeenth century.

As a work of visual art, the Biblia Pauperum reflects numerous typological details beyond what the Biblical texts and commentaries on each leaf explain. In line with this outlook, the 120 panels of the blockbook constitute a handbook of Biblical iconography and typology, useful in understanding the organizing principles of religious art, notably illuminated manuscripts, illustrated Bibles, frescoes, painting, sculptures, woodcuts, emblem books and stained glass windows in convents, churches and cathedrals. Even a kinetic art form such as medieval drama uses dialogue, action, scenery, and stage properties that may be interpreted in relation to the iconographic and typological details in the Biblia Pauperum. Thus, The Sacrifice of Isaac in the Corpus Christi Cycle dramatizes Isaac with a fagot on his back and in the company of his father as they travel to a mount, prefigurations of the way of the cross and the journey up the hill to Golgotha. Finally, the iconography and typology of the Biblia Pauperum enrich one’s outlook on the mimetic or imitative ritual of sacramental celebration. Accordingly, the triptych (i) that features the Baptism of the Lord — flanked, on the left, by the Red Sea deliverance and, on the right, by the carrying of the stalk of grapes across the Jordan River — presents an enriched interpretation of the baptismal experience. The triptych (s) showing the Last Supper, with Melchizedek at the left and the Israelites’ gathering of manna at the right, combines Eucharistic symbolism with suggestions of induction into the priesthood.

Because of its panoramic outlook — from the Annunciation to the Apocalyptic union of the blessed souls with the Lord — the Biblia Pauperum develops a view whereby history unfolds sub specie aeternitatis or under the eye of God and according to his plan. As such, the series of woodcuts in the blockbook may be likened to other encyclopedic affirmations of the Providential scheme in human history. Medieval plays — the York, Towneley, Coventry and Chester cycles — feature many of the same events, including the Baptism of the Lord, the Temptation of Jesus, and the Transfiguration, that are highlighted in the central panels of the Biblia Pauperum. Sequences in medieval stained glass (the windows of King’s College Chapel or the lancets under the west rose of Chartres, at times with stone sculptures of prophets nearby) resemble the architectonics of the Biblia Pauperum, whose pillars, arches, and onlooking Old Testament personages suggest the arcade or triforium of a Gothic Cathedral.

As a graphic manifestation of the Christian world view in the Middle Ages, the Biblia Pauperum is highly representative, if not commonplace, in its iconography, typology, selection of Biblical texts, and interpretive commentary. Little purpose is served by noting antecedents for particular verbal or visual elements in the blockbook. Such annotation would be voluminous, and its use and value questionable. Thus, for instance, the Biblical image of the cross as a fishhook (Job 40:20) in the twenty-fifth triptych (.e.) recurs in the commentary of the Church Fathers — Irenaeus, Origen, Gregory of Nyssa, Gregory of Nazianzen, Gregory the Great, Rupert Deutz, Honorius of Autun, Rabanus Maurus and others. The image suggests that Christ is the bait to lure Leviathan, while the cross is the means to hook and bridle him. The Old Testament image, its New Testament antitype, the relationship of the passage from Job to other Biblical texts that appear with it in the Biblia Pauperum, and the iconographic resemblances of the cross, not only to the fishhook, but to other images in the twenty-fifth triptych (.e.), emerge from an inveterate tradition that spans more than a thousand years. For us, the Biblia Pauperum is one example of a popular work in this tradition of visualizing and interpreting Scripture. To examine the origin and development of this tradition, as well as variations therein, is beyond the scope of our present enterprise.

In addition to its selective exposition of Scripture by typology and iconography, the Biblia Pauperum also aimed to edify its audience, concerning the life of Christ. Coupled with intellectual understanding, in other words, was an emotional response of devotion and gratitude for Christ’s ministry of Redemption, emphasized in scenes of the Passion and Crucifixion. This dual purpose of exposition and edification, effectively commingled and efficiently executed in the blockbook, was aptly suited to the "poor man," not simply to his level of understanding but to his threshold of emotional response.

If, therefore, one were to assess the thrust of the moral imagination reflected in the Biblia Pauperum, the dominant outlook was to depict humiliation and eventual triumph — what may be called, in effect, a theology of suffering. Christ’s suffering was the prototype after which one’s life and even death or martyrdom could be modeled. The effect of such living and dying could have twofold application — to energize the populace toward the revolutionary reform of an oppressive culture and government or to offer a transcendent outlook on one’s circumstances, whereby the reward of suffering is perceived as the heavenly kingdom, not the improvement of one’s circumstances in the present life. Either way, the heroism exemplified by Christ, involving faith, patience, and fortitude to withstand increasing adversity, is perhaps the foremost assertion of the Biblia Pauperum and the principal lesson to be derived from its art, Biblical texts and commentary.