From Open Bible Info blog: Archive for the ‘Visualizations’ Category: yes it is very long:

Saturday, July 18th, 2015

The images that come to mind when you think of heaven aren’t the same ones you would’ve conjured had you lived a hundred, five hundred, a thousand, or two thousand years ago. The word heaven accretes and shifts meaning over time–the cosmology of the Israelites who first heard the creation story in Genesis, for example, uses the metaphor of a “firmament” to explain the structure of the heavens, while your idea of the physical heavens probably involves outer space and Pluto.

Or take angels. Before the Renaissance, you wouldn’t have pictured a cherub as a chubby baby, yet today the first image that comes to mind when you think of angels might very well be this:

From Raphael’s Sistine Madonna, 1512

Linguists can pinpoint precisely when English speakers started to use cherub to refer to a child in this way: 1705. (The OED entry for cherub elaborates that this image developed further during the 1800s. Thank you, Victorians.)

Researchers from the University of Glasgow have created a website that explores how metaphors from different semantic domains (“angels” and “children,” for example) bleed into each other over time: Mapping Metaphor.

While the website lets you visualize the data in a number of ways, I thought it would be interesting to combine a couple of their visualizations to clarify (for myself) the historical cross-pollination of some Bible-related metaphors in English.

The first chart shows how metaphors have shifted over time for heaven and hell. The arrows indicate the direction of the metaphor. For example, an arrow points from height to heaven because linguistically we apply the real-world idea of height to the location of heaven: the metaphor points from the concrete to the abstract. Conversely, when the arrow goes the other direction, as from heaven to good, the metaphor points from the abstract to the concrete. When we say, “This tastes heavenly,” for example, we’re applying some qualities of heaven to whatever we’re eating.

The second chart explores the application of metaphors relating to angels and the devil. The Mapping Metaphor blog discusses this metaphorical angel/devil dichotomy in some detail.

There’s also data for Deity (i.e., God), but its historical connections overlap so much with other (mostly Greek) deities that it’s not so useful for my purpose here.

Finally, I want to mention that the source data for the Mapping Metaphor project, The Historical Thesaurus of English, is itself a fascinating resource. It arranges the whole of the English language throughout history into an ontology with the three root categories represented by color in the above images: the external world, the mental world, and the social world. Any hierarchical ontology raises the usual epistemological questions, but I think the approach is fascinating. The result is effectively a cultural ontology (at least to the extent that language encodes culture).

I compared a few Historical Thesaurus entries to the Lexham Cultural Ontology (designed for ancient literature) and found a surprising degree of correlation: all the entries I looked up in Lexham mapped to one or a combination of two entries in the Historical Thesaurus. Considering that we know (pdf, slide 33) that people who write linguistic notes in their Bibles are more interested in the meanings of English words than they are in the definitions of the original Hebrew and Greek words, I wonder whether an English-language-based ontology might prove a fruitful approach to indexing ancient literature–at least for English speakers.

Via PhD Mama.

Posted in Art, Linguistics, Visualizations | Comments Off on Visualizing historical English metaphors related to the Bible

Wednesday, May 13th, 2015

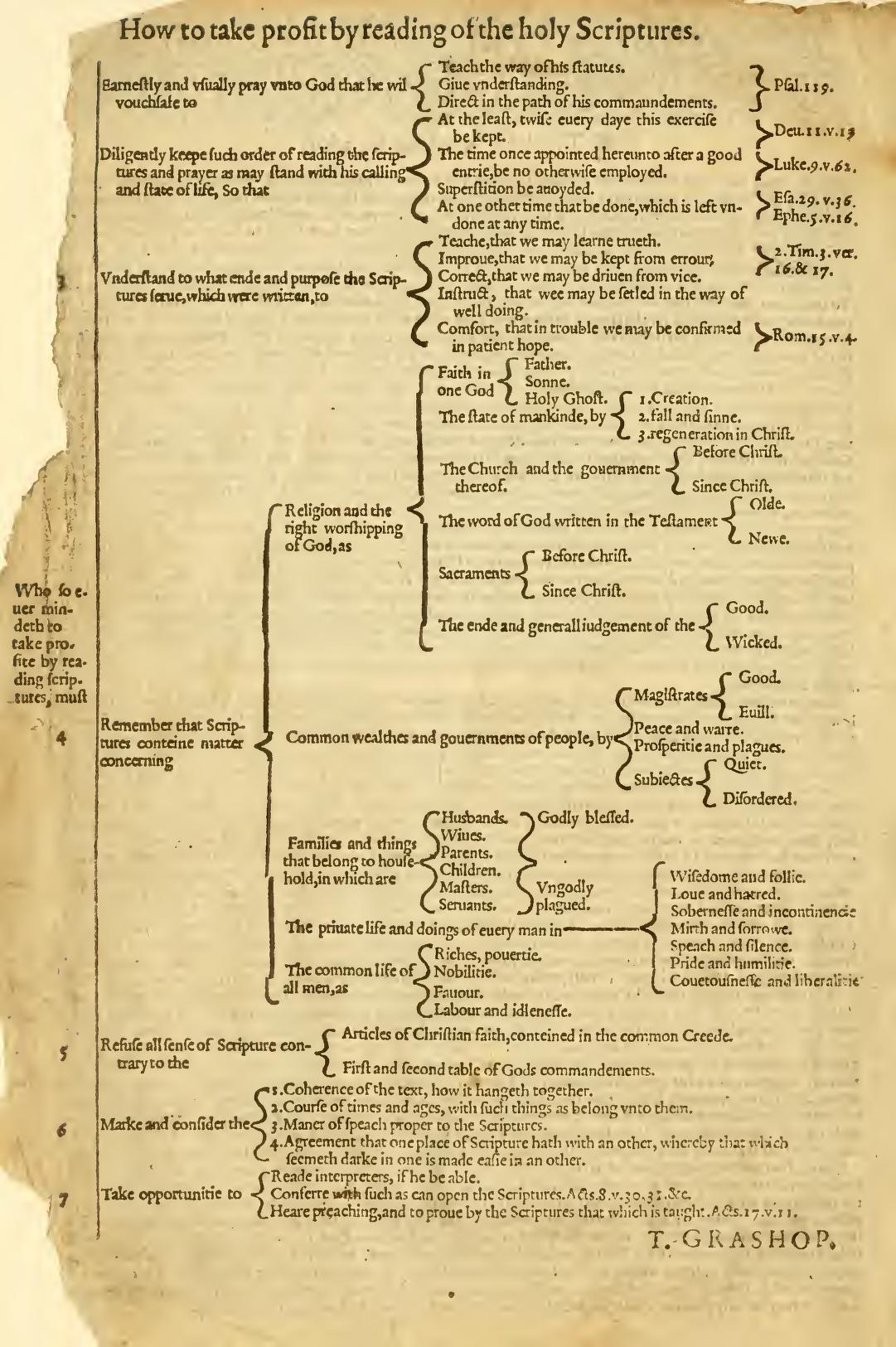

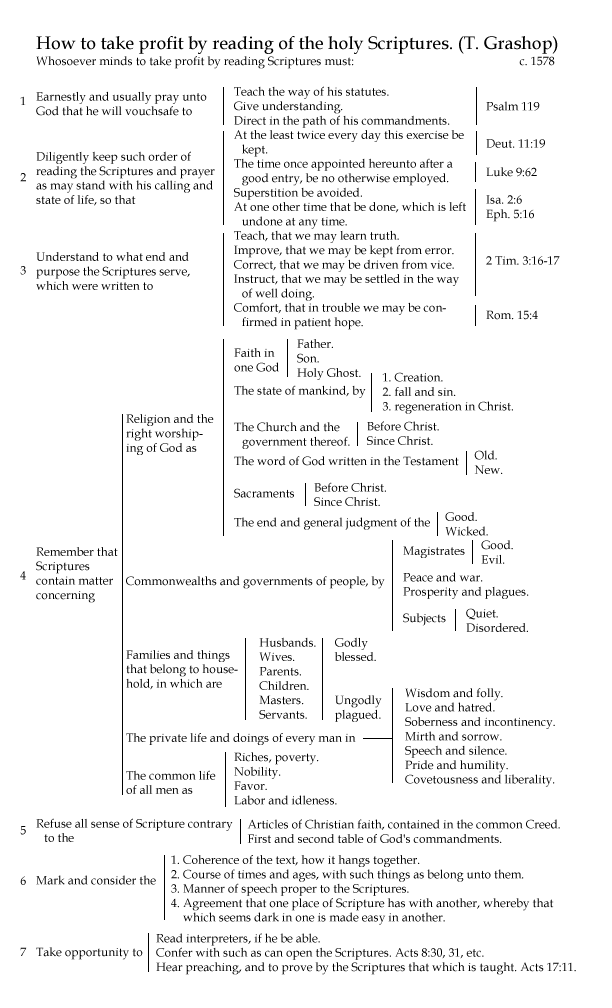

Many printings of the Geneva Bible after 1579 contain the following flowchart by T. Grashop. This flowchart reflects the Renaissance obsession with ordering the world using tree diagrams and presents a systematic approach to studying the Bible. I share it here to show that “mind-mapping” Bible study isn’t a new idea; it has extensive historical roots.

Credit: archive.org

Below is a reproduction I created with modernized spelling and design. I particularly want to note the reference to Isaiah 29:36 in this chart. This verse doesn’t exist. If anyone knows what verse Grashop might have meant, especially as it relates to “Superstition be avoided” when studying the Bible, I’d be interested in correcting this 400-year-old typo. Sean Boisen in the comments presents a plausible case that it should be Isaiah 2:6.

Also available in PDF: 8.5×11 inches or 8.5×14 inches (full size).

I consider all these Grashop-related files to be in the public domain; if you want to reuse them, you don’t need to credit anyone.

Posted in History, Visualizations | 2 Comments »

Thursday, January 1st, 2015

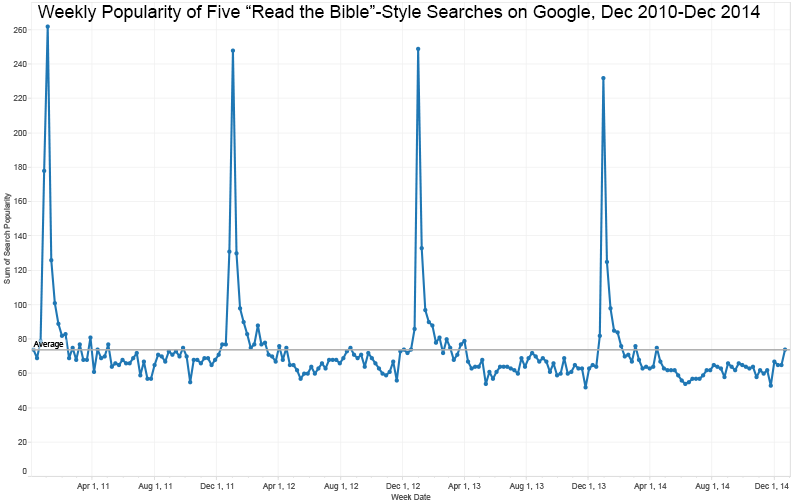

Just in case you wonder how seasonal people’s interest in reading the Bible is, here’s a chart from Google Trends showing five “read through the Bible”-related search terms. The peaks every January speak for themselves. You can see a secondary peak in August or September when classes get underway at many schools.

If we take some of the above data, plot it by week rather than by month, and add it together, the effect is even more vivid:

(This chart goes through December 27, 2014.)

You see huge peaks just before and after January 1 each year, along with a small bump around Easter and the aforementioned mellow spike in August or September. The interest related to the new year is almost entirely gone by February. You could interpret this drop as “Everyone who’s interested has already found their reading plan for the year,” or you could interpret it as, “Well, Genesis was interesting. Maybe I’ll read through the Bible next year.”

Inspired by Google Trends of Popular New Year’s Resolutions.

Posted in Reading, Visualizations | Comments Off on Seasonal Interest in Bible Reading Plans

Tuesday, December 30th, 2014

Bible Gateway recently shared their most-popular Bible verses of 2014, and I wanted to discuss this chart a little more:

The chart stems from the idea that if someone is equally likely to see a verse on any day of the year, each day should have 1/365, or 0.27%, of a verse’s yearly popularity. This chart shows days when there’s a spike in pageviews for each verse for a particular day (whenever it was over 0.4% of the annual total).

The theme of the chart is that people follow certain paths through the Bible during the year; I labeled a few of them on the chart. But there are definitely a few patterns I can’t explain:

- At the beginning of the year, two lines emanate from Genesis that look like they’re on track to read the full Bible in a year, but one of them is faster than the other. Why are there two?

- At the bottom right of the chart is a shallow line that looks like it involves reading Genesis and Exodus starting in May and ending in December. There’s a similar line in the New Testament running through Matthew from June to November. What are those?

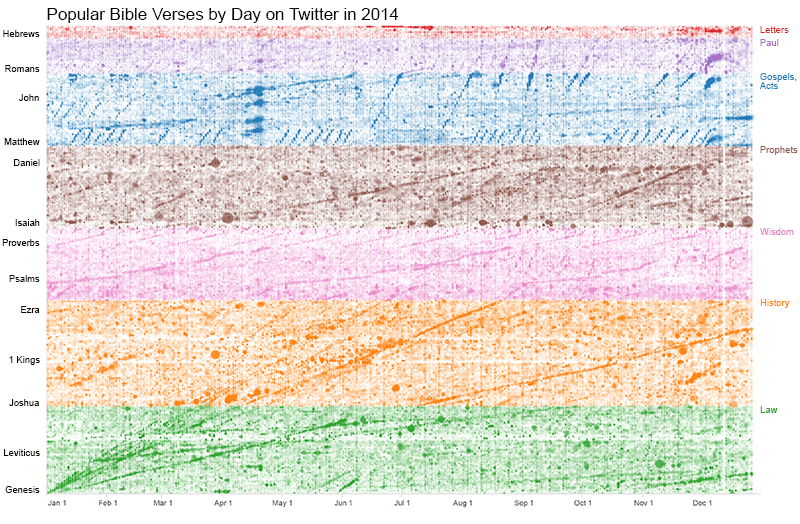

I was curious whether the same patterns would appear in Twitter for the year, so I ran a similar analysis on the 43 million tweets this year that mentioned Bible verses. The answer is that, yes, you can see many of the same paths in both charts:

They even include the same two (or three or four) fast readings of the Bible at the beginning of the year and the slow reading of Genesis and Exodus in the second half of the year. You can see similar peaks around the Passion stories leading to Easter and the Nativity story leading to Christmas. (Christmas is the last day that appears on this chart.) The Twitter chart more clearly shows the weekly rhythms of the devotional life, with vertical lines just barely visible every Sunday. The main difference is that there’s not as clear a path through the New Testament.

The Twitter chart also shows some horizontal bands where sharing is pretty light. These “sharing shadows” appear in the opening chapters of Numbers, 1 Kings, and 1 Chronicles.

Prolific Verse Sharers

A quirk of the Twitter chart is that some Twitterers tweet (and are retweeted) a lot. I suspect many of them are bots, but it’s hard to say whether they constitute “Bible spam”–many people do appear to find them helpful by retweeting them. The top fifty or so Twitterers are responsible for 16 million of the 43 million tweets this year. The chart doesn’t look too different if you remove them (mostly, the frequent repetition of Matthew disappears), but that just could be because I didn’t remove enough users to affect the results meaningfully. For all I know, this chart mostly just shows how Twitter bots share the Bible during the year. The consistency with the Bible Gateway data (in which I have more confidence), however, leads me to think that this picture is reasonably accurate.

Here are the top non-bot (as far as I can tell) sharers of Bible verses–these people tweeted the most Bible verses (and, more importantly, were retweeted most) throughout the year. Some of these people I recognize, and others… not so much. The “tweet” numbers reflect only tweets containing Bible verses and include others’ retweets of their tweets.

- JohnPiper (105,836 tweets)

- DangeRussWilson (87,382 tweets)

- WeLiftYourName (52,638 tweets)

- JosephPrince (50,889 tweets)

- BishopJakes (49,109 tweets)

- siwon407 (48,994 tweets)

- RickWarren (42,637 tweets)

- JoyceMeyer (39,703 tweets)

- jeremycamp (32,003 tweets)

- DaveRamsey (28,173 tweets)

- RCCGworldwide (26,731 tweets)

- AdamCappa (25,976 tweets)

- Creflo_Dollar (24,422 tweets)

- sadierob (20,068 tweets)

- Carson_Case (19,846 tweets)

- TimTebow (18,303 tweets)

- Kevinwoo91 (17,230 tweets)

- levimitchell (16,355 tweets)

- jesse_duplantis (15,755 tweets)

- kutless (14,806 tweets)

Most-Popular Verses

Here are the most-popular verses shared on Twitter in 2014:

- Phil 4:13 (613,161 tweets)

- 1Pet 5:7 (261,417 tweets)

- Prov 3:5 (218,019 tweets)

- John 14:6 (212,883 tweets)

- John 13:7 (207,084 tweets)

- 1Cor 13:4 (197,379 tweets)

- Matt 28:20 (187,407 tweets)

- Ps 118:24 (183,475 tweets)

- 2Tim 1:7 (182,758 tweets)

- Ps 56:3 (180,139 tweets)

You can also download a text file (411 KB) with the complete list of 2014’s popular verses.

John 13:7 (“Jesus replied, ‘You do not realize now what I am doing, but later you will understand.'”) is the oddball here, but it turns out that it’s mostly from over 100,000 retweets of a single tweet in April. (Since it was a one-off, I omitted him from the list of top sharers above, although his tweet count of 163,497 would put him in first place.)

How do the year’s most-popular verses compare among Bible Gateway, YouVersion, and Twitter? The answer: there’s a good deal of variation. Below are the top ten from each service; only Proverbs 3:5 appears in all three lists, and YouVersion and Twitter only have one verse that overlaps, which surprises me (given that they’re both based on sharing).

If we look only at Bible Gateway and Twitter, the average verse differs in its ranking by about 3,000 places, or nearly 10% of the Bible. The largest differences in rank: 1 Kings 20:14 is much more popular on Twitter (rank 4,380) than on Bible Gateway (rank 27,119), while Ezra 5:14 is way more popular on Bible Gateway (rank 13,995) than Twitter (rank 30,018).

Bold entries appear in at least two lists.

Data Source

The Twitter data is from Bible Verses on Twitter. A program connects to the Twitter Streaming API with a query for every chapter of the Bible (“Gen 1”, “Genesis 1”, and so on). I run a Bible reference parser on the tweet to pull out all the references. Then an SVM algorithm tries to guess whether the tweet is actually talking about a Bible verse or just happens to contain a string that looks like a Bible reference (“Gen 1 XBox for sale,” where “Gen” is short for “Generation”).

Sidenote: How I Calculate Verse Views

A note on methodology: I’ve never documented how I determine a particular verse’s popularity; now’s a good time, because you can do it a number of ways to reach different answers. Let’s say that someone is looking at Genesis 1, which has 31 verses. That counts as one pageview, but if you’re looking for the number of pageviews that, say, Genesis 1:1 receives, how do attribute a chapter-length view like this? You could give each verse credit for a full pageview, but then verses in long chapters will appear to have a disproportionately high number of pageviews. Instead, I prefer to divide the pageview into the number of verses in the passage: in this case, each verse in Genesis 1 will receive 1/31, or 0.032 pageviews.

Now, what if someone is looking at, say, Genesis 1:1 and Matthew 1 (25 verses) on the same page? In this case, I divide the pageview by the number of separate passages: Genesis 1:1 receives credit for a full 0.5 pageviews, as does Matthew 1. Each verse in Matthew 1 therefore receives 0.5/25, or 0.02 pageviews.

I feel that this approach best respects people’s intentions whether they want to look at multiple verses, several independent passages, or just individual verses.

Posted in Bible, Twitter, Visualizations | Comments Off on The Bible on Twitter in 2014

Tuesday, December 24th, 2013

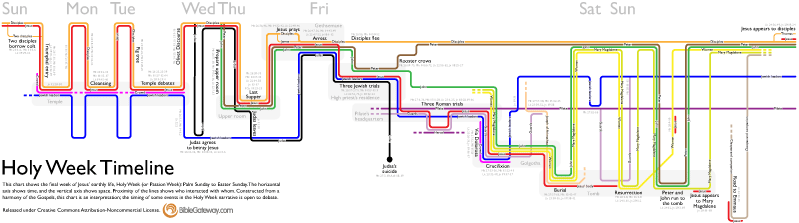

Over at the Bible Gateway Blog, I have a post discussing the above Christmas Timeline Visualization, which uses the same xkcd-inspired format as the Holy Week Timeline from 2011.

Sequencing the events of the Christmas story in the Bible to produce this visualization raises a few questions I’d never considered before (not that they’re unique to me):

- When does Mary conceive Jesus? Everyone (including several commentaries) says that it happens before Mary goes to visit Elizabeth. John the Baptist’s leap for joy in the womb is generally thought of as a response to Jesus’ proximity, but the text says that Mary’s voice prompts it. Even Elizabeth’s blessing doesn’t necessarily imply that Mary is already carrying Jesus.

- Did any of the shepherds who visited Jesus on the night of his birth have children whom Herod would later kill in the “Slaughter of the Innocents?” If so, that adds a chilling undertone to the story.

- Did the magi stay in the same inn at Bethlehem that didn’t have room for Mary and Joseph?

- Why do angels always inspire movement? Every time they show up in the story, someone heads off somewhere.

Thanks to my assistant for putting together the spreadsheet (CSV) containing all the data used in the visualization.

Posted in Visualizations | Comments Off on Christmas Timeline Visualization

Tuesday, February 7th, 2012

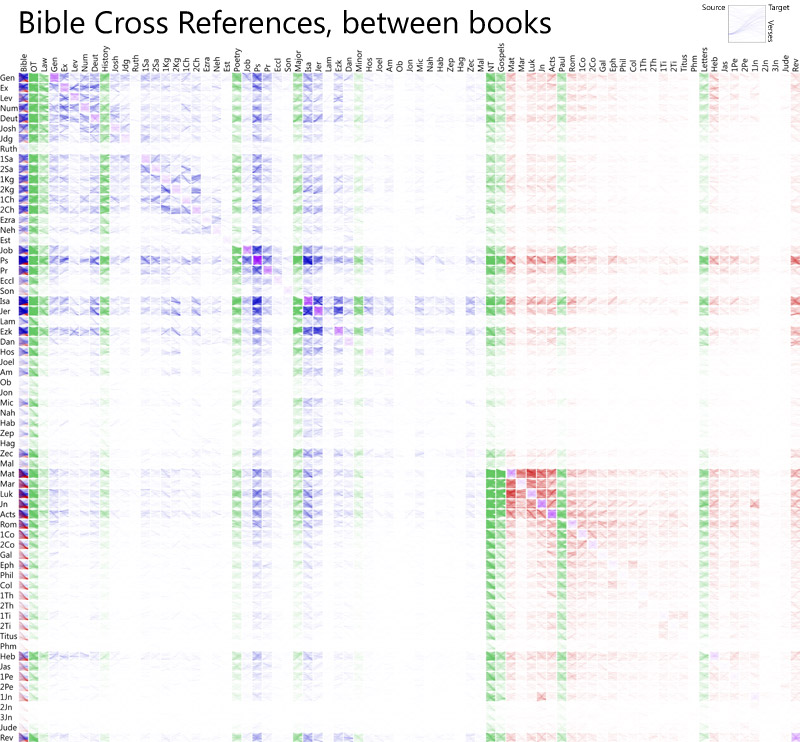

Browse this grid interactively.

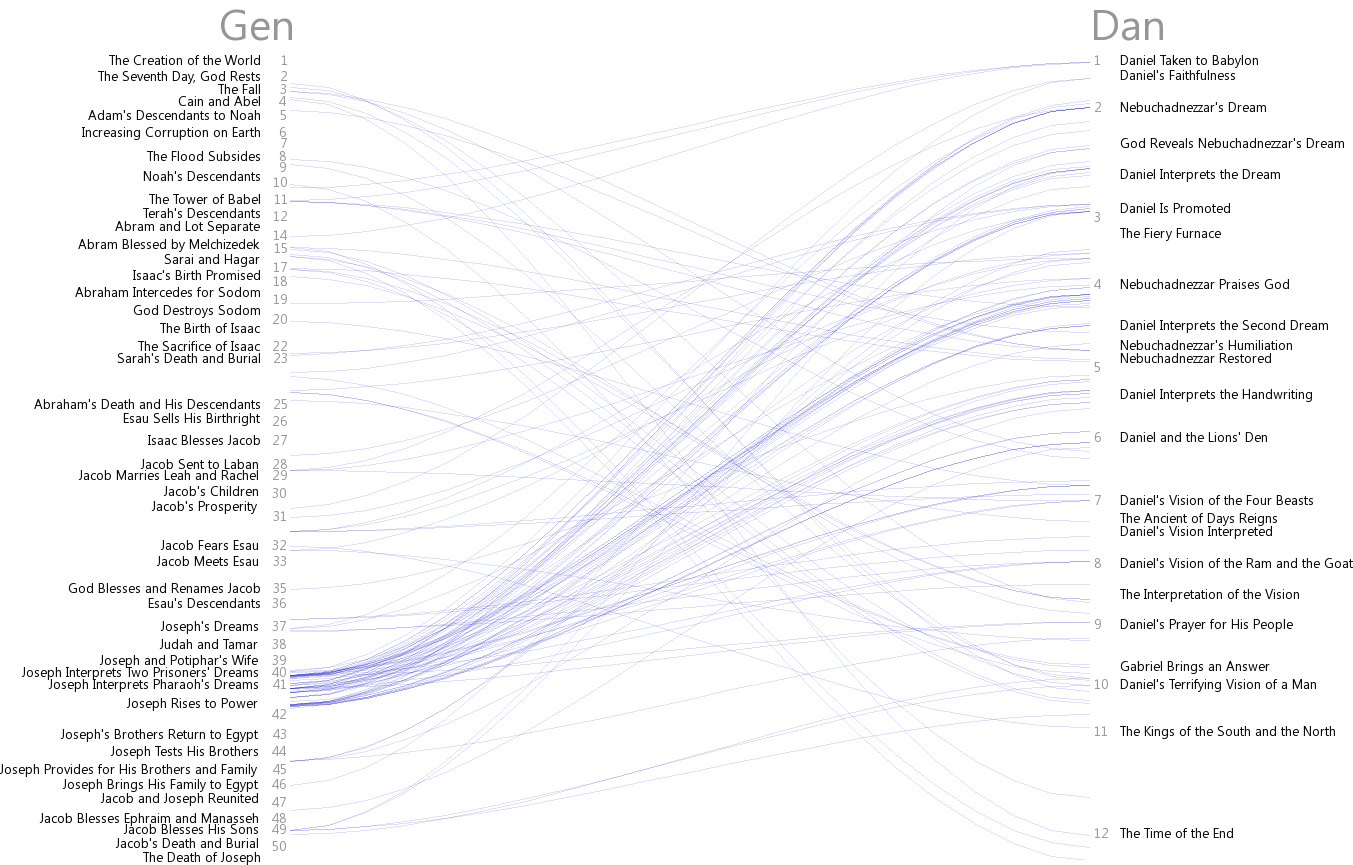

This visualization is arranged by book, showing cross-reference sources on the y-axis and targets on the x-axis. Within each square, the first verse in the book or section is at the top, and the last verse is at the bottom. Here’s what a detail of a square looks like:

Genesis 1 is at the top left; Genesis 50 is at the bottom left. Daniel 1 is at the top right; Daniel 12 is at the bottom right. The most-striking cross references between these two books, to me, involve Joseph’s interpretation of dreams in Genesis 40-41 and similar stories in Daniel.

Also see a previous cross reference visualization.

Posted in Cross References, Visualizations | 2 Comments »

Monday, October 10th, 2011

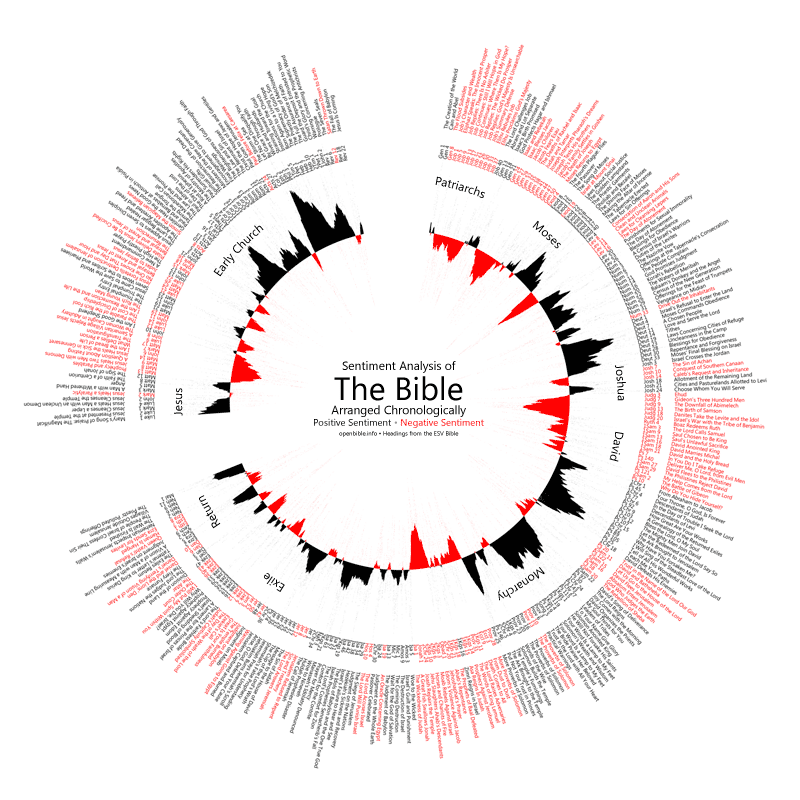

This visualization explores the ups and downs of the Bible narrative, using sentiment analysis to quantify when positive and negative events are happening:

Full size download (.png, 4000×4000 pixels).

Things start off well with creation, turn negative with Job and the patriarchs, improve again with Moses, dip with the period of the judges, recover with David, and have a mixed record (especially negative when Samaria is around) during the monarchy. The exilic period isn’t as negative as you might expect, nor the return period as positive. In the New Testament, things start off fine with Jesus, then quickly turn negative as opposition to his message grows. The story of the early church, especially in the epistles, is largely positive.

Methodology

Sentiment analysis involves algorithmically determining if a piece of text is positive (“I like cheese”) or negative (“I hate cheese”). Think of it as Kurt Vonnegut’s story shapes backed by quantitative data.

I ran the Viralheat Sentiment API over several Bible translations to produce a composite sentiment average for each verse. Strictly speaking, the Viralheat API only returns a probability that the given text is positive or negative, not the intensity of the sentiment. For this purpose, however, probability works as a decent proxy for intensity.

The visualization takes a moving average of the data to provide a coherent story; the raw data is more jittery. Download the raw data (400 KB .zip).

Update October 10, 2011

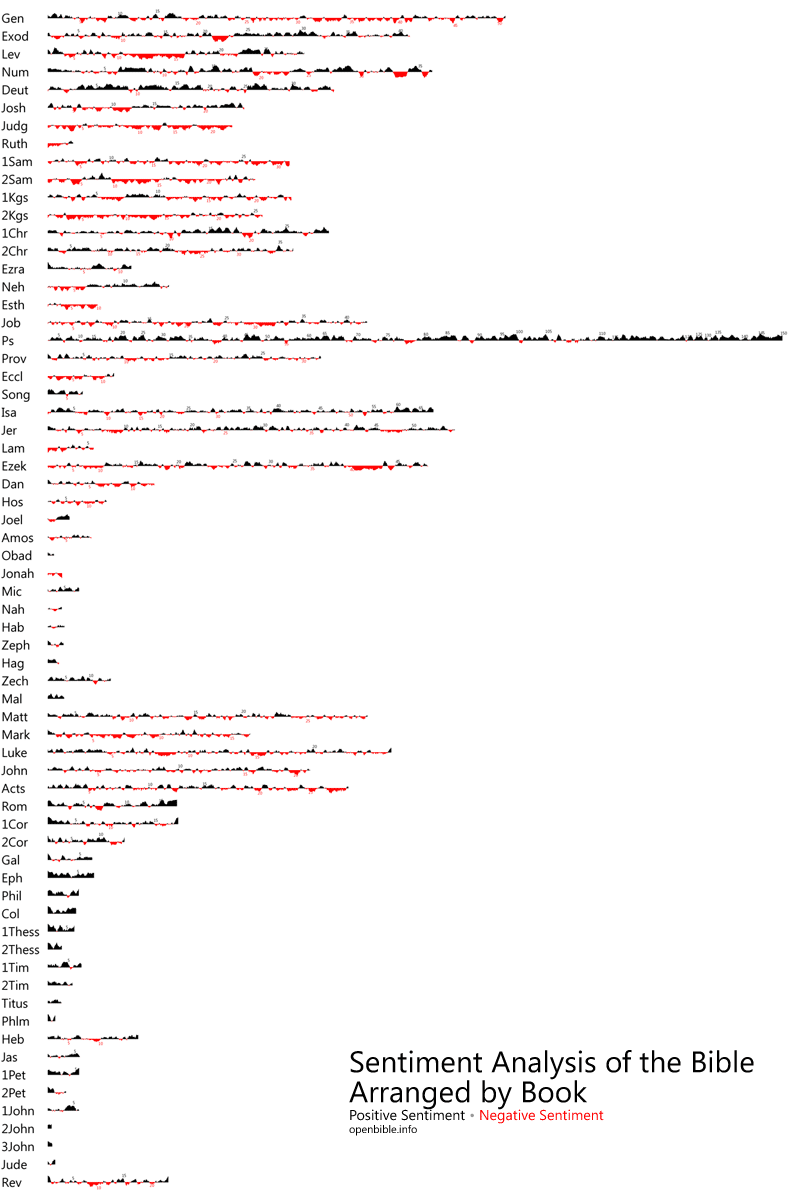

As requested in the comments, here’s the data arranged by book with a moving average of five verses on either side. (By comparison, the above visualization uses a moving average of 150 verses on either side.)

Full size download (.png, 2680×4000 pixels).

Update December 28, 2011: Christianity Today includes this visualization in their December issue (“How the Bible Feels”).

Posted in Sentiment, Visualizations | 41 Comments »

Thursday, September 1st, 2011

If you’re storing people’s Bible annotations (notes, bookmarks, highlights, etc.) digitally, you want to be able to retrieve them later. Let’s look at some strategies for how to store and look up these annotations.

Know What You’re Modeling

First you need to understand the shape of the data. I don’t have access to a large repository of Bible annotations, but the Twitter and Facebook Bible citations from the Realtime Bible Search section of this website provide a good approximation of how people cite the Bible. (Quite a few Facebook posts appear to involve people responding to their daily devotions.) These tweets and posts are public, and private annotations may take on a slightly different form, but the general shape of the data should be similar: nearly all (99%) refer to a chapter or less.

Compare Bible Gateway reading habits, which are much heavier on chapter-level usage, but 98% of accesses still involve a chapter or less.

The Numbers

The data consists of about 35 million total references.

| Percent of Total | Description | Example |

|---|

| 73.5 |

Single verse |

John 3:16 |

| 17.1 |

Verse range in a single chapter |

John 3:16-17 |

| 8.4 |

Exactly one chapter |

John 3 |

| 0.7 |

Two or more chapters (at chapter boundaries) |

John 3-4 |

| 0.1 |

Verses spanning two chapters (not at chapter boundaries) |

John 3:16-4:2 |

| 0.1 |

Verses spanning three or more chapters (not at chapter boundaries) |

John 3:16-5:2 |

About 92.9% of posts or tweets cited only one verse or verse range; 7.1% mentioned more than one verse range. Of the latter, 77% cited exactly two verse ranges; the highest had 323 independent verse ranges. Of Facebook posts, 9.1% contained multiple verse ranges, compared to 4.2% of tweets. When there were multiple ranges, 43% of the time they referred to verses in different books from the other ranges; 39% referred to verses in the same book (but not in the same chapter); and 18% referred to verses in the same chapter. (This distribution is a unusual—normally close verses stick together.)

The data, oddly, doesn’t contain any references that span multiple books. Less than 0.01% of passage accesses span multiple books on Bible Gateway, which is probably a useful upper bound for this type of data.

Key Points

- Nearly all citations involve verses in the same chapter; only 1% involve verses in multiple chapters.

- Of the 1% spanning two or more chapters, most refer to exact chapter boundaries.

- Multiple-book references are even more unusual (under 0.01%) but have outsize effects: an annotation that references Genesis 1 to Revelation 22 would be relevant for every verse in the Bible.

- Around 7% of notes contained multiple independent ranges of verses—the more text you allow for an annotation, the more likely someone is to mention multiple verses.

Download

Download the raw social data (1.4 MB zip) under the usual CC-Attribution license.

Data Modeling

A Bible annotation consists of arbitrary content (a highlight might have one kind of content, while a proper note might have a title, body, attachments, etc., but modeling the content itself isn’t the point of this piece) tied to one or more Bible references:

- A single verse (John 3:16).

- A single range (John 3:16-17).

- Multiple verses or ranges (John 3:16, John 3:18-19)

The Relational Model

One user can have many rows of annotations, and one annotation can have many rows of verses that it refers to. To model a Bible annotation relationally, we set up three tables that look something like this:

users

annotations

| user_id | annotation_id | content |

|---|

| 1 |

101 |

… |

| 1 |

102 |

… |

| 1 |

103 |

… |

annotation_verses

The verse references here are integers to allow for easy range searches: 43 = John (the 43rd book in the typical Protestant Bible); 003 = the third chapter; the last three digits = the verse number.

I like using this approach over others (sequential integer or separate columns for book, chapter, and verse) because it limits the need for a lookup table. (You just need to know that 43 = John, and then you can find any verse or range of verses in that book.) It also lets you find all the annotations for a particular chapter without having to know how many verses are in the chapter. (The longest chapter in the Bible has 176 verses, so you know that all the verses in John 3, for example, fall between 43003001 and 43003176.) This main disadvantage is that you don’t necessarily know how many verses you’re selecting until after you’ve selected them. And using individual columns, unlike here, does allow you to run group by queries to get easy counts.

| annotation_id | start_verse | end_verse |

|---|

| 101 |

43003016 |

43003016 |

| 102 |

43003016 |

43003017 |

| 103 |

43003016 |

43003016 |

| 103 |

43003019 |

43003020 |

Querying

In a Bible application, the usual mode of accessing annotations is by passage: if you’re looking at John 3:16-18, you want to see all your annotations that apply to that passage.

Querying MySQL

In SQL terms:

select distinct(annotations.annotation_id)<br /> from annotations, annotation_verses<br /> where annotation_verses.start_verse <= 43003018 and<br /> annotation_verses.end_verse >= 43003016 and<br /> annotations.user_id = 1 and<br /> annotations.annotation_id = annotation_verses.annotation_id<br /> order by annotation_verses.start_verse asc, annotation_verses.end_verse desc

The quirkiest part of the SQL is the first part of the “where” clause, which at first glance looks backward: why is the last verse in the start_verse field and the first verse in the end_verse field? Because the start_verse and end_verse can span any range of verses, you need to make sure that you get any range that overlaps the verses you’re looking for: in other words, the start_verse is before the end of the range, and the end_verse is after the start.

Visually, you can think of each start_verse and end_verse pair as a line: if the line overlaps the shaded area you’re looking for, then it’s a relevant annotation. If not, it’s not relevant. There are six cases:

The other trick in the SQL is the sort order: you generally want to see annotations in canonical order, starting with the longest range first. In other words, you start with an annotation about John 3, then to a section inside John 3, then to individual verses. In this way, you move from the broadest annotations to the narrowest annotations. You may want to switch up this order, but it makes a good default.

The relational approach works pretty well. If you worry about the performance implications of the SQL join, you can always put the user_id in annotation_verses or use a view or something.

Querying CouchDB

CouchDB is one of the oldest entrants in the NoSQL space and distinguishes itself by being both a key-value store and queryable using map-reduce: the usual way to access more than one document in a single query is to write Javascript to output the data you want. It lets you create complex keys to query by, so you might think that you can generate a key like [start_verse,end_verse] and query it like this: ?startkey=[0,43003016]&endkey=[43003018,99999999]

But no. Views are one-dimensional, meaning that CouchDB doesn’t even look at the second element in the key if the first one matches the query. For example, an annotation with both a start and end verse of 19001001 matches the above query, which isn’t useful for this purpose.

I can think of two ways to get around this limitation, both of which have drawbacks.

GeoCouch

CouchDB has a plugin called GeoCouch that lets you query geographic data, which actually maps well to this data model. (I didn’t come up with this approach on my own: see Efficient Time-based Range Queries in CouchDB using GeoCouch for the background.)

The basic idea is to treat each start_verse,end_verse pair as a point on a two-dimensional grid. Here’s the above social data plotted this way:

The line bisects the grid diagonally since an end_verse never precedes a start_verse: the diagonal line where start_verse = end_verse indicates the lower bound of any reference. Here are some points indicating where ranges fall on the plot:

To find all the annotations relevant to John 3:16-18, we draw a region starting in the upper left and continuing to the point 43003018,43003016:

GeoCouch allows exactly this kind of bounding-box query: ?bbox=0,43003016,43003018,99999999

You can even support multiple users in this scheme: just give everyone their own, independent box. I might occupy 1×1 (with an annotation at 1.43003016,1.43003016), while you might occupy 2×2 (with an annotation at 2.43003016,2.43003016); queries for our annotations would never overlap. Each whole number to the left of the decimal acts as a namespace.

The drawbacks:

- The results aren’t sorted in a useful way. You’ll need to do sorting on the client side or in a show function.

- You don’t get pagination.

Repetition at Intervals

Given the shape of the data, which is overwhelmingly chapter-bound (and lookups, which at least on Bible Gateway are chapter-based), you could simply repeat chapter-spanning annotations at the beginning of every chapter. In the worst case annotation (Genesis 1-Revelation 22), you end up with about 1200 repetitions.

For example, in the Genesis-Revelation case, for John 3 you might create a key like [43000000.01001001,66022021] so that it sorts at the beginning of the chapter—and if you have multiple annotations with different start verses, they stay sorted properly.

To get annotations for John 3:16-18, you’d query for ?startkey=[43003000]&endkey=[43003018,{}]

The drawbacks:

- You have to filter out all the irrelevant annotations: if you have a lot of annotations about John 3:14, you have to skip through them all before you get to the ones about John 3:16.

- You have to filter out duplicates when the range you’re querying for spans multiple chapters.

- You’re repeating yourself, though given how rarely a multi-chapter span (let alone a multi-book span) happens in the wild, it might not matter that much.

Other CouchDB Approaches

Both these approaches assume that you want to make only one query to retrieve the data. If you’re willing to make multiple queries, you could create different list functions and query them in parallel: for example, you could have one for single-chapter annotations and one for multi-chapter annotations. See interval trees and geohashes for additional ideas. You could also introduce a separate query layer, such as elasticsearch, to sit on top of CouchDB.

Posted in Data Modeling, Twitter, Visualizations | 2 Comments »

Saturday, April 16th, 2011

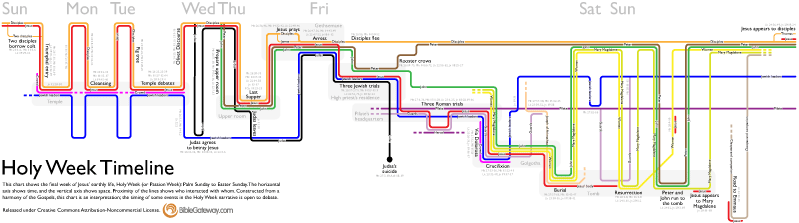

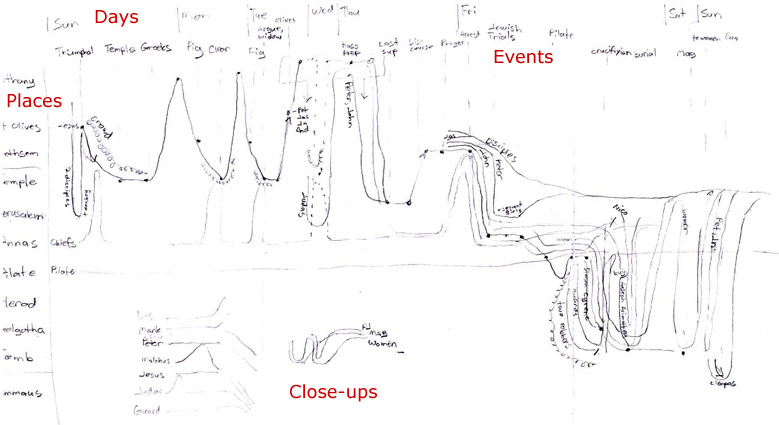

It’s always fun for me to learn the process people use to create visualizations, and especially why they made the decisions they did. So please forgive me if you find this post self-indulgent; I’m going to talk about the new Holy Week Timeline that’s on the Bible Gateway blog:

The idea for this visualization started in November 2009 when xkcd published its movie narrative charts comic, which bubbled up through the Internet and shortly thereafter became a meme. Although the charts are really just setting up a joke for the last two panels in the comic, they’re also a fantastic way of visualizing narratives, providing a quick way to see what’s going on in a story at any point in time. The format also forces you to consider what’s happening offstage—it’s not like the other characters cease to exist just because you’re not seeing them and hearing about them.

My first thought was to plot the book of Acts this way, but Acts presented too broad a scope to manage in a reasonable timeframe. Holy Week then came to mind—it involves a limited amount of time and space, it doesn’t feature too many characters, and the Gospels recount it in a good bit of detail: one Gospel often fills in gaps in another’s account.

Now I needed data. (Data is always the holdup in creating visualizations.) Fortunately, Gospel harmonies are prevalent, even free ones online. The version of Logos I have includes A. T. Robertson’s Harmony of the Gospels, so I started transcribing verse references from the pericopes listed there into a spreadsheet, identifying who’s in each one and when and where it takes place. I plowed halfway through, but then other priorities arose, and I had to abandon hopes of completing it in time for Holy Week 2010.

It lay dormant for a year (there’s not a lot of reason to publish something on Holy Week unless Holy Week is nigh). A few weeks ago, I finished itemizing the people, places, and times in Robertson. Justin Taylor last year published a harmony of Holy Week based on the ESV Study Bible, which had a slightly different take on the timeline (one that made more sense to me in certain areas), so I moved a few things around on my spreadsheet. I also consulted a couple of other study Bibles and books I had readily available to me.

With data in hand, it was time to put pencil to paper.

Version 1: Paper

I wanted to make four basic changes to the xkcd comic: use the vertical axis consistently to show spatial progression, provide close-ups for complex narrative sequences, include every character and event, and add the days of the week to orient the viewer in time. Only the last of these changes wound up in the final product, however.

The vertical axis in this version proceeded from Bethany at the top, through the Mount of Olives and various places in Jerusalem, and ended at Emmaus. On a map of Holy Week events, this axis approximates a line running from east (Bethany) to west (Emmaus). Using the vertical axis this way encodes more information into the chart, allowing you to see everything that happened in a single location simply by following an imaginary horizontal line across the chart. Unfortunately, it also leads to a lopsided chart that progresses down and to the right, creating huge amounts of whitespace on a rectangular canvas. I didn’t see that problem yet, however.

I did see that the right half of the chart (Friday to Sunday) was much denser than the left half—I’d need to space that out better when creating a digital version.

Version 2: Drawing Freehand in Illustrator

I have a confession: I’d never used Adobe Illustrator before this project. Most of my image work uses pixels; Photoshop is my constant companion. But this project would have to use vectors to allow for the constant fiddling necessary to produce a decent result at multiple sizes. So, Illustrator it was.

My first goal was to reproduce the pencil drawing with reasonable fidelity. I used my mouse to draw deliberately wobbly lines that mimicked the xkcd comic. Now, if I’d had more experience with Illustrator, the hand-drawn effect may have worked. But making changes was incredibly annoying; I had to delete sections, redraw them, and then join them to the existing lines. It took forever to make minor tweaks; what would I do when I needed to move whole lines around (as frequently happened later in the process)? After all, if you look closely, you’ll see entire swaths of the chart misplaced. (Why are the disciples hanging out in the Temple after Jesus’ arrest?) No, this hand-drawn approach was impractical for someone of my limited Illustrator experience. I needed straight lines and a grid.

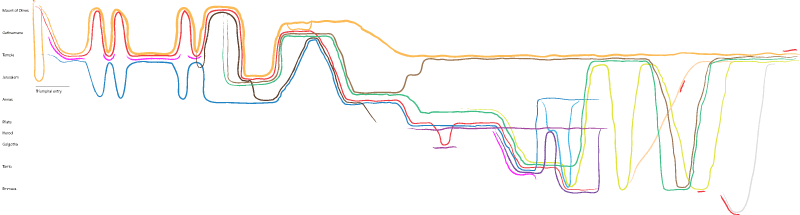

Version 3: The Grid

My wife says that this version reminds her of 1970s-style album covers. She’s right. Nevertheless, it formed the foundation of the final product.

So, what are the problems here? First, the lines weigh too much. Having given up a pure freehand approach, I wanted a more transit-style map (used for subways / the Underground) with straight lines and restricted angles. I’m most familiar with Chicago’s CTA map and thought I’d emulate their style of thick lines that almost touch. This approach leads to lots of heavy lines that don’t convey additional information—it’s also tricky to round the corners of such thick lines without unsightly gaps appearing (again, for someone of my limited Illustrator experience).

The second problem is the extreme weight in the upper left of the chart, far out of proportion to the gravity of events there. The green, brown, and black lines represent Peter, James, and Judas, who don’t play prominent roles until later in the story. They’re adding lots of “ink” to the chart and not conveying useful information. They had to go.

Why not simply lighten the colors–after all, why is Judas’s line black? Simple: black often represents evil. Similarly, Jesus’ line is red to represent his blood. The Jewish leaders are blue because it contrasts well with red, and most of the chart involves conflict between Jesus and the Jewish leaders (with the pink crowd usually acting as a buffer to prevent Jesus’ arrest). Pilate and Herod are imperial purple. Orange is similar in hue to Jesus’ red, so the disciples are orange. I tried not to get too heavy-handed with the symbolism, but there it is.

Most of the other colors are arbitrary (i.e., available in Illustrator’s default palette and of roughly the same saturation as the symbolic colors). John would be sharing a lot of space on the chart with Mary Magdalene and the other women, so I tried to give them colors (green, olive, yellow) that worked well together. The only future change from the color scheme in this version involves the guards, who change from cyan (too bright) to a light purple.

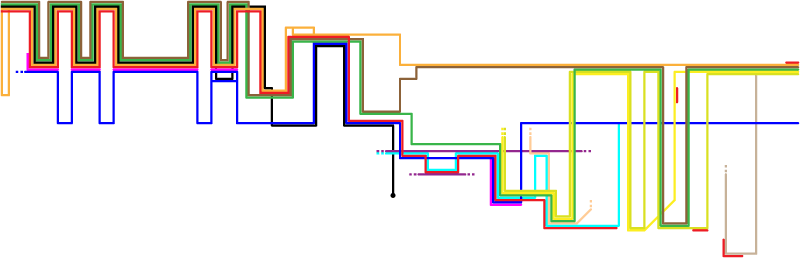

Version 4: Less Technicolor

This version reduced the line weight and introduced Peter, John, and Judas only when they needed to appear as independent entities in the story. It works better, but there are still two problems with it.

First, look at the giant areas of whitespace in the bottom left and top right (especially the top right). Using the vertical axis to indicate absolute travel through space is a nice idea, but I couldn’t figure out how to do it without creating these huge gaps. In the next version, I abandoned the vertical-axis-as-space idea—it now indicated travel between places, but you could no longer follow a horizontal line to see everything that happened in a single place.

Second, I realized that I wouldn’t be able to incorporate every event and person, as they added clutter. I could have added close-ups to illustrate these details—obviously there was enough space for them. However, I felt that including them would distract from the main point: to show Holy Week at a glance. I’m still a bit torn over omitting them, but I think it was a better decision to reduce the total space used by the chart.

I also abandoned the idea that Jesus went to the Temple on Wednesday. Some commentators think he did; others disagree. From a story-structure standpoint, I like the idea that Judas slipped away from the other disciples to bargain for his thirty pieces of silver while Jesus was teaching in the Temple. However, the text is ambiguous on when exactly Judas agreed to betray Jesus and what Jesus was doing on Wednesday.

Version 5: Text

This is the final version. It condenses a lot of vertical and horizontal space; moves some lines around so they overlap less; and, most importantly, adds text: titles for major events; shading and place names for major locations; verse references; line labels; and a short explanation.

The xkcd chart is brilliant in that it doesn’t need a key: following recent trends in UI design, all the labels are inline. I definitely wanted to keep that approach, which meant making lots of labels and placing them on the lines. Again, my lack of experience with Illustrator showed up: I couldn’t get the text to center on the lines automatically, and I had trouble creating an outer glow on the text to provide some contrast with the background and make sure that the text was legible. (Black text on a bright blue background is an unpleasant combination.) But the glow always ate into the letters. Thus, I ended up creating lots of pixel-perfect, partially transparent rectangles as backgrounds for the labels. Some of the person lines had somehow slipped out of alignment with the grid, so I had to do a lot of clicking to get things back into order. In retrospect, it was good that I had to make the rectangles; I might not otherwise have noticed that the lines weren’t all where they were supposed to be.

The shaded boxes to indicate places are straight-up rounded rectangles (though I’m not sure why the corner radius is a global application preference in Illustrator). These boxes, borrowed from xkcd, replace the vertical-axis idea I earlier toyed with.

Finally, I added event titles and verse references. Here I tried to be comprehensive, including references even when I didn’t have a title to put with them. For example, there are two fig tree stories in the Gospels, but I only titled one of them. The references are available to you if you want to read both, though.

Conclusion

This project was fun, if time-consuming. In total, it took somewhere between forty and sixty hours (much of it spent climbing Illustrator’s learning curve). The chart ended up looking less like the xkcd comic and more like a transit map than I was expecting at the outset, but that’s OK. I’m now a whole lot more familiar with the Holy Week timeline, and I hope that others find the chart useful, too. If it helps improve Bible literacy even a little bit, then I consider it a success.

Posted in Visualizations | 2 Comments »

Thursday, March 10th, 2011

Congratulations, I guess, go this year to Charlie Sheen, who came in at both #23 and, with “tiger blood,” at #90. Justin Bieber is up several spots this year, so he hasn’t quite crested yet. The next-highest celebrity, who didn’t make the top 100, is British boy band One Direction.

“Trophies,” at #69, refers to the English soccer club Arsenal‘s recent defeat, or something.

The later start to Lent this year means that “snow” doesn’t appear on the list–last year, it was #48. Myspace hangs on at #99, dropping 48 places.

This list draws from 85,000 tweets from March 7-10, 2011, and excludes retweets.

| Rank | Word | Count | Change from last year’s rank |

|---|

| 1. |

Twitter |

4297 |

0 |

| 2. |

Facebook |

4060 |

0 |

| 3. |

Chocolate |

3185 |

0 |

| 4. |

Swearing |

2527 |

+1 |

| 5. |

Alcohol |

2347 |

-1 |

| 6. |

Sex |

2093 |

+3 |

| 7. |

Soda |

1959 |

-1 |

| 8. |

Lent |

1493 |

-1 |

| 9. |

Meat |

1352 |

-1 |

| 10. |

Fast food |

1303 |

0 |

| 11. |

Sweets |

1252 |

0 |

| 12. |

Giving up things |

778 |

+7 |

| 13. |

School |

768 |

+27 |

| 14. |

Religion |

745 |

+1 |

| 15. |

Coffee |

707 |

-3 |

| 16. |

You |

675 |

+6 |

| 17. |

Social networking |

665 |

+15 |

| 18. |

Chips |

664 |

+3 |

| 19. |

Junk food |

594 |

-1 |

| 20. |

Bread |

<t