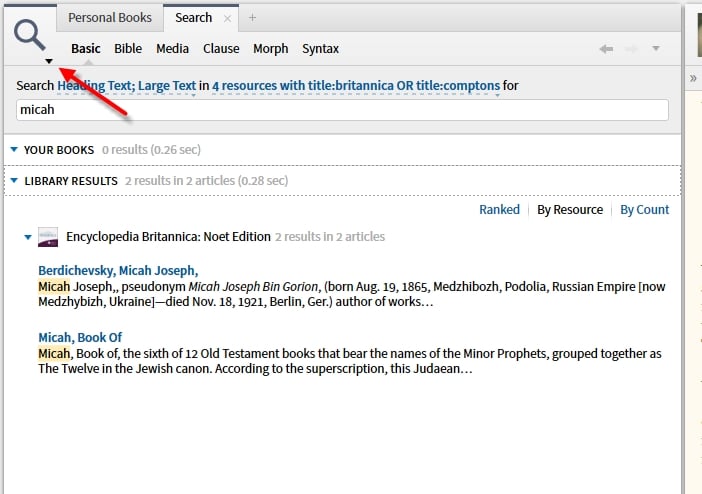

How do I search for particular verses in selected resources?

My suggestion would be to create collections of resources you might commonly seek search results from (e.g. commentaries, favorite commentaries, favorite bible dictionaries, etc)

https://wiki.logos.com/Collections

How to I get it to display the same verse in all Bibles?

However, I took a look and found a way to do what you want without much difficulty:

(1) Open Acts 3:21 in any version of the Bible.

(2) Right click on any word within Acts 3:21.

(3) In the context menu, click on "Acts 3:21" in the right-hand column.

(4) In the left hand column, click on "Power Lookup." This will show that verse in every version in your Bible, as well as other resources such as commentaries.

TIP: Power Lookup will reflect the prioritization of your resources. If you want to use it for comparing Bible translations first, then you will want all your English translations to be prioritized first in your prioritization list.

Another option is to use Text Comparison. If you are only comparing a few translations, the Horizontal Layout will work fine, but if you are going to compare every translation in your library, you'll want to use Vertical Layout.

Follow these steps:

(1) Click on Tools > Text Comparison.

(2) Add all the versions you want to see in the second box (first box is for the reference), separate each version with a comma (,). Example: KJV, NKJV, ESV, NASB95, NRSV . . .

(3) To change the layout to vertical, click the big square box with two arrows in it to the left of the reference box and select "Vertical Layout."

Now, with this open, you can type in any reference (or reference range) to get a comparison with all the versions you included. You can also use "Link Set" to have it update while reading the Bible.

Yet another thing you can do is with Acts 3:21 open and selected, press F7 (or FN+F7) on your keyboard and it will provide you with a pop-up comparison of your top five prioritized Bibles.

How do I use the Command Box to open Help?

I just discovered this today and am posting it for those who like me were not aware of or did not think of trying this before. Most of us would be familiar with the Open (resource) to (reference) command, esp. for Bibles as in typing open NASB95 to John 1:19 will in the command box will open the NASB95 at this reference.

But we can do this with the help file as well. Try open help to factbook.

Sadly, at this point, you have to put the exact header for this to work. So, if you put "advanced search" you will not get there, because the header is "advanced searching" and logos does not offer suggestions based on what you wrote (as they do with resource titles) and * or ? do not work as wildcards.

How does Logos determine where to open a resource?

This question comes up periodically.

Short answer: There's broad consensus that the tiled layout we have in L4/5/6 is great, except that panel opening is kind of mysterious. We'd like to fix that, too, but it's much more complicated than it might first seem.

Long answer:

L2 and L3 were what's called a multi document interface, or MDI. An MDI is basically windows-within-windows where can open multiple "document" (in our case document, resource, tool, and guide) windows inside of the main application. These child windows work like regular application windows in all respects, except that they are contained within their parent window (the app). They can be maximized, minimized, and most importantly, they can overlap.

The new window opening algorithm was simple: New resources on the right, new tools/reports on the left. This worked really well as long as you never deviated from the two vertical halves left and right layout.

When we did our user research for the L4 design, we found that many many users were experiencing frustration because their windows were overlapping and partially or wholly obscuring windows "behind." (L3 had a sort of rudimentary "tab" interface, but that would only work if you locked in two or more windows to exactly the same X,Y coordinates and size. So it failed easily and often.) Minimizing a window didn't really make it go away, it just made it tiny and shoved it to the bottom left corner, behind everything else.

We also asked users to send us screen shots of their favorite work setups. We found that every single one of them used all the empty space on the screen with no gaps. When we watched users creating these layouts, we also found that they spent a lot (and I mean A LOT) of wasted clicks and drags fiddling with the borders of child windows to cover the gaps. We found several people intentionally left a small strip of empty space in the lower-left corner of the screen. Puzzled, we asked those users why they set it up that way. It was so that minimized windows wouldn't get "lost" but would go into this little gap in the lower left.

Our design solution to both of these problems was to create a tiled layout system where every window is "docked" into a portion of the screen and all of the screen real estate is used (with the exception that we only use one half when there's only one tile). This solved all of the foregoing problems very elegantly. It's a very sophisticated docking/tiling system that (if I may say myself), I've never seen equaled. With the true tabbing system on top of the automatic space-filling tile layout system, it's really second to none.

In the L4/5/6 layout system, the screen is divided into tiles that a) must occupy all the available space, and b) cannot overlap.

But every design comes with trade-offs. In the old system, the panel opening logic was dead simple. In the new system, you could create any layout with impunity and be certain that no windows were lost. But the rule that tiles cannot overlap means that the panel opening algorithm has to choose which tile to open a new tab into.

Turns out, there isn't a right answer, because sometimes you want like panels stacked on top of each other (eg, all Bibles in the upper-right corner) but sometimes you don't (eg, you're reading these translations side-by-side to compare). We decided on this heuristic, which isn't perfect:

(1) Some panels should open in a new floating window because their content is large. For example, Timeline. Other panels we think should open in sidebars, for example, Favorites.

(2) Of the remaining panels, we first check for open empty space, and open there. If there's no empty space, we compare the metadata of all open tiles and open the new panel into the tile that most closely matches. So, if you stack a lot of Bible dictionaries into a corner, it's more likely (but not guaranteed) that opening another Bible dictionary will stack on top.

(3) HOWEVER, there's a final rule, and that is that if you open a new panel from a hyperlink, we try very hard not to open that new panel on top of the one you just clicked in (ie, the one you're working with). We originally didn't have this rule and found a lot of users weren't happen that clicking a Bible reference in a commentary was likely to open the Bible over top of the commentary they were reading (and other similar situations -- clicking anywhere in a Passage Guide pretty much assured that Passage Guide was going to get covered up).

This heuristic creates a certain unpredictability to panel opening that we don't particularly care for, either, but it's the least-worst alternative.

We have several ideas for how to give a panel a user-specified preference on where to open. Current thinking is that the simplest approach is to attack rule #1 in the heuristic above: Let people decide for new default locations (main layout, left sidebar, right sidebar, or new floating window) for whichever panels they feel most strongly about. Some people, for example, almost always drag Text Comparison out of the right sidebar into the main layout, because they want to see the comparisons side-by-side instead of stacked on top of one another. You should be able to tell Logos that's your style, and to stick to it.

Other ideas have users drawing out empty tiles in their preferred layout, with some sort of rule system to guide newly opened panels to those tiles, sort of like Collection rules. For example, you could draw a rectangle on the upper-right corner and declare that "type:bible" goes there, no questions asked. (Lots of corner cases here.)

Maybe one or the other. Maybe both. Maybe, maybe — someday.

One thing we won't do is go back to a classic MDI interface. Those have (thankfully) mostly died out.

I hope that's a helpful explanation of how we got where we are and were we might go from here. Happy hunting!

How do I create a collection of my resources omitting the fiction?

The identification of fiction resources would have to be based on subject tagging. I.e., this will give you a list of fiction books:

subject:fiction

and inversely, this should give a list of books that aren't fiction:

* -subject:fiction

But since most of the fiction books in my library are Vyrso or Personal Books, it's most likely they are not matched. Plus you can't really rely on the Library of Congress subject tagging to be consistent.

So I've taken to adding a personal tag of "fiction" to each fiction book I own to better identify them. And so I can use this rule:

* -subject:fiction -tag:fiction

This rule also takes advantage of community tags; so if others have tagged a book as fiction then it will be excluded.

Start by filtering Library with edition:ebook (Vyrso titles) and tag the fiction titles (select multiple titles to give them the same tag).

Your collection rule would then look like, for example type:monograph -mytag:fiction (non-fiction monographs)

EDIT: Based on Todd's response, my rule would become:-

type:monograph -mytag:fiction -subject:fiction

but you still have to tag personal books (edition:user) and some Faithlife books (edition:logos type:monograph) as fiction.

Start by filtering Library with edition:ebook (Vyrso titles) and tag the fiction titles (select multiple titles to give them the same tag).

Your collection rule would then look like, for example type:monograph -mytag:fiction (non-fiction monographs)

EDIT: Based on Todd's response, my rule would become:-

type:monograph -mytag:fiction -subject:fiction

but you still have to tag personal books (edition:user) and some Faithlife books (edition:logos type:monograph) as fiction.

How can I copy the text comparison keeping the column format?

Enter the reference range you want in the box at the top of the panel and hit enter. Then select the print option from the panel menu. Print to an RTF file and open the result in Word.

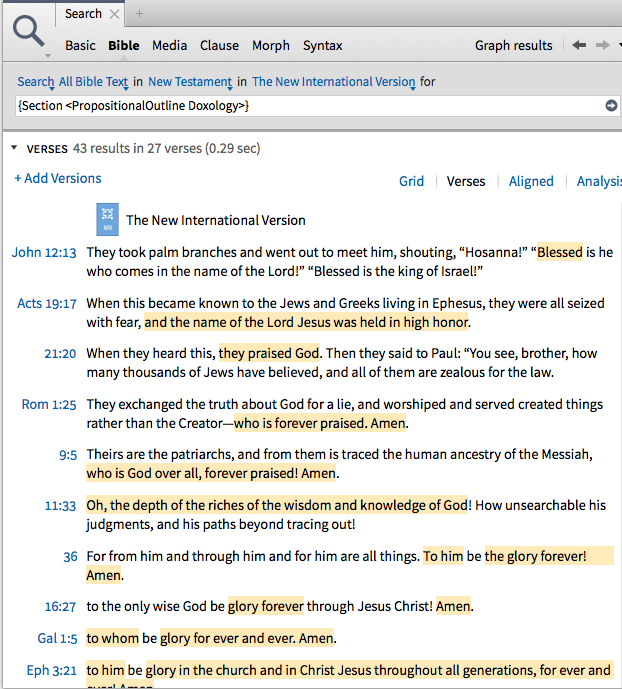

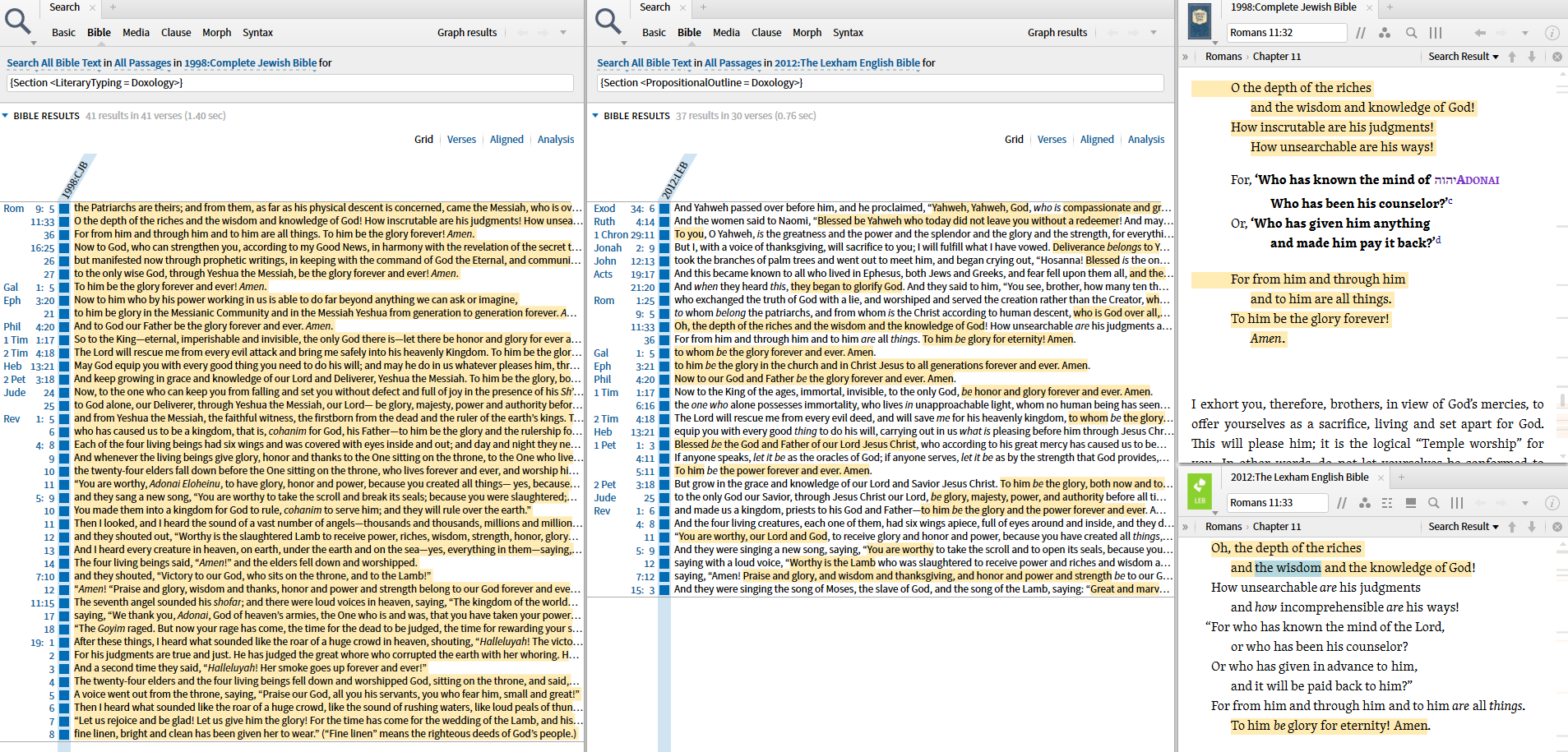

How do I find all the doxologies of the New Testament?

First, the answer: {Section <PropositionalOutline = Doxology>} in Bible search.

Second, the way I found it which can help you and others find this kind of answers in the future: (1) go to a passage that corresponds to what you are looking for (here a doxology); (2) explore the context menu to see how it is tagged (as it turns out, Rom 11:33 does have <> Doxology - Propositional Outline in its context menu); (3) if you find the tag you are looking for, search from it (from the context menu, search this resource) to get the right search syntax. (4) Use this syntax as a baseline from which you can formulate searches with more parameters.

NB: I did this from the ESV. Not all Bibles are necessarily all tagged for all the same things.

First, the answer: {Section <PropositionalOutline = Doxology>} in Bible search.

Another Bible Search is:

{Section <LiteraryTyping = Doxology>}

Keep Smiling

How do I search for all references to places in the Gospel of John?

Wow....and <Places ANY> or <Places *> seems like such a no brainer.....

Concordance tool, limit passages to John, then filter by the Entity:Place

Concordance does not include Jerusalem, Jordan, Bethany, Bethsaida, Nazareth (all in Jn 1), & Cana (in Jn 2) and others.

It also fails by including referents that are verbs, adverbs, pronouns.

Cities needs to be selected to to get the additional ones that Dave mentioned. I don't think you can select both places and cities in the Concordance Tool. Another approach is the Bible Browser (Logos Now)

Louw-Nida Semantic Domain 93 has Names of Persons (1-388) and Places (389-615) so can do a Bible Search for Names of Places in John:

<Louw Nida 93.389–93.615>

This is more accurate, but omits Israel (93.182) and includes adjectives like Judean.

(<Louw Nida 93.389–93.615>, <LN 93.182>) ANDEQUALS <LogosMorphGr ~ N????> is better, and helps diagnose where Concordance omits places.

Try the Explorer tool. It covers it all!

Am I missing something about how to export to a passage list?

after testing, it's not possible directly from Explorer, but if you run the same range through the passage guide, it works, after you select the "show all" option at the bottom of the Biblical Places section. (Also remember to collapse all sections of the guide when running such a long passage range)...

Well, first let me say that you are right, there should be an easy way to do this, it should be possible from the search panel with a simple <Place ANY> or something like that, it should be possible from the Bible Browser, etc.

That being said... here is a workaround solution until it is.

- In the Explorer, collapse all sections except for Biblical Places. Then run a search for John 1-21.

- Right click on the header, and select "Copy."

- Open up Microsoft Word, and paste the results into Word. You'll have one place on each line.

- Open up the Search and Replace dialog box. Run the following search and replace. In the "Find what", you are searching for "Paragraph Mark", which you can select from the "Special" button on the bottom left of the Find and Replace dialog. What we are doing is searching for carriage returns, and replacing them with the <Place> format Logos needs:

5. Fix the first and last one manually in Microsoft Word.

6. You'll end up with the following search string, which you can then search for in your preferred Bible, limiting yourself to the Gospel of John, with all the places reported by the Explorer:

<Place Galilee>, <Place Bethany (on the Mt. of Olives)>, <Place Sychar>, <Place Golgotha>, <Place Jerusalem>, <Place Judea>, <Place Sea of Galilee>, <Place Capernaum>, <Place Jordan>, <Place Samaria (city)>, <Place Cana>, <Place Nazareth>, <Place Siloam>, <Place Israel>, <Place Bethsaida>, <Place Kidron>, <Place Mount Gerizim>, <Place Bethany (Beyond the Jordan)>, <Place Jacob’s Well>, <Place Aenon>, <Place Bethlehem (of Judah)>, <Place Ophrah (of Benjamin)>, <Place Tiberias>, <Place Beth-Zatha>, <Place Salim>, <Place Places John the Baptist went>, <Place Any Place>, <Place Ramah (of Benjamin)>, <Place Mount of Olives>, <Place Places Jesus went>

7. From your Search Panel menu, select "Save as Passage List." Give it a new name if you like. FYI, I got 88 verses.

8. If you want your single, full list in canonical order to be usable in a document as a pure list of references: In the Passage List you just created, select Print/Export. Then, on the left hand pane, select "Print as minimized list". Finally, select "Copy to clipboard."

How do I print or save my search results?

click the resource panel menu, (in this case the magnifying glass) and select print/export...

How do I delete a Prayer List?

Right-click on it in the Documents menu.

How are <...>, {...}, ~ "..."used in Search syntax?

<...> is used for datatype searching - for searching within a dataset

{...} is used for extending regular search capabilities and do not require additional datsets

This is outlined at https://wiki.logos.com/Search_HELP#New_Datatypes

If you want a more general rule, generally datatypes (e.g. <>) will represent individual points of data, whilst the special searches (e.g. {}), will tend to identify longer sections.

You need to be thinking about what searches will return (as we're talking about search syntax).

If you search for <Bible John 1:1-19:1>, each result will be an individual point of data (e.g. John 3:3, John 18:1-25, John 19:1, etc.), and you'll see the search highlights dotted about resources. The same is true for almost any other datatype search.

On the other hand, special searches will tend to return long sections, often with whole paragraphs highlighted.

The <...> syntax was introduced in Logos 4 to differentiate textual queries from data type reference queries.

How are the following queries different?

The first finds articles that have both ‘John’ and ‘3:16’ somewhere in the article. The second finds those two terms, but requires them to be adjacent, i.e., an exact phrase. The third uses Logos’ data type reference technology to find text that has been tagged with the Bible reference Jn 3:16; this might include “John 3:16”, “Jn III. 16”, “see v.16”, “16”, etc. And by default, it also finds intersecting references, so it'll match John 3:16–18, John 3:1–16, etc. (This can be customised by specifying an operator, e.g., <=John 3:16>.)

For more on data type reference searching, see:

The {...} syntax was introduced in Logos 6 for “search extensions”. These are hard to describe briefly, because each one can be implemented quite differently; in fact, their purpose is to extend the search engine by finding data that isn't stored in the full text index. As a result, you probably have to learn each one individually; there isn't usually a general rule that applies to all of them. (FWIW, {...} was chosen because we needed a way to differentiate these from “regular” queries and those characters weren't already in use.)

- {Milestone <Reference>} — uses a resource’s milestone index (unrelated to the full text index) to find the portion of a resource that's tagged as a milestone for the given reference. Use normal data type reference syntax to specify the reference.

- {Speaker <Reference>} / {Addressee <Reference>} — uses the Reported Speech dataset to find original language or reverse-interlinear-aligned text tagged as reported speech. Use data type reference syntax to specify the person or thing that's speaking.

- {Highlight Palette/Style} — uses your notes to find text marked with the specified highlighting style

- {PassageList Name} — performs a data type reference search for all of the passages in a specified passage list

- {Label query} — provides a mini SQL-like language for finding label references; the matched references may come from supplemental data resources, label tagging inside resources themselves (this actually does come from the full text index), labels attached to your own highlights. Implemented as a search extension because it specifies a query for finding many matching label references.

- {Section ...} — perhaps one of the most “vague” extensions. Uses supplemental data resources to find results from datasets that can be purchased for Logos 7. Consult the corresponding dataset documentation for specific details.

I'll take a shot.

< > indicates that your are search for a reference to something. Rather than looking at the text in the resource, this search looks for special tags that Faithlife has added to the resource indicating that the text refers to a particular thing. The things that are tagged are extremely broad. The easiest way to learn about these are to right-click on some text in a resource. Selecting many of the items on the right side of the menu and then selecting "Search all resources" on the left side will generate a search using this syntax. The search syntax indicates the type of thing being looked for, an optional symbol you can ignore for now, and the exact reference you are searching for. By right clicking in a Bible, I can generate the following searches:

- <Place Midian (region)> is searching for text that has a "Place" tag indicating it is the region of Midian.

- <LogosMorphHeb = NP-SA> is search for text that has a "hebrew morphology" tag indicating singular absolute proper noun.

- <Lemma = lbs/he/מִדְיָן:2> is a search for text that has a "lemma" tag indicating that the word has a lemma of lbs/he/מִדְיָן:2

The problem with these is that you really can't manually build these searches until you are familiar with the type of data you are searching for, so unless it's a reference to a Bible passage you are looking for, just build them with the right click menu.

{ } doesn't really have any special meaning. What is significant is the first word you find after the opening {. This word indicates what kind of search is being made, and defines the parameters that need to be used. If you want to keep things simple, don't worry about it. Instead, build your search by right clicking on something that you want to search for, select the appropriate type of data on the right side of the menu, and then chose the search on the left side. This generates the search without having to worry about the syntax. More examples from the Bible:

- {Section <PreachingTheme = Clothing>} is searching for a Section of text that is marked with a PreachingTheme tag (note the similarity to the syntax above) indicating the theme of clothing.

- {Label Longacre Genre WHERE Primary ~ <LongacreGenre Expository: What things will be like>} is searching for text where a Longacre Genre Label has been added where the label has a primary... meh... it search for places that talk about what things will be like.

See how those really get to complicated to explain simply? Don't worry about them. Just right click and search.

If you rely on the right click menu technique to build your searches, then you only need to learn about how to connect multiple searches together to find places where tagging overlaps each other (for example, finding a certain morphology that is also in a section marked with the clothing preaching theme.

E.g. Why does Place use <> while Speaker / Addressee use {} just from a commonsense, non-techie point of view? They both seem to be invisible, human-curated tags Faithlife added to enrich the text.

From a more technical point of view, the tagging for datatypes (searched for using < >) are stored directly in the resource. So if you're searching for

{ } searches are much more powerful for several reasons.

First, they're stored in separate datasets, which means they can be applied to multiple resources. For example, {Section <Culture = Marriage>}, you'll get results from more than 350 resources. None of those 350 resources have been tagged for the Culture datatype. But there's a separate Cultural Concepts dataset that knows (for example), that Genesis 29:22 is a reference to marriage. When you search for {Section <Culture = Marriage>} Logos is looking at the Cultural Concepts dataset, finding all the references that match, then searching all your other resources for those references. It's a great way of extending search capabilities without the expense of tagging hundreds of resources. There are exceptions to this, {Milestone} being the most obvious example.

Second, you're usually able to search for datatypes as part of a search extension, so you can do things like:

- {Milestone <Bible Jn 3:16>}

- {Speaker <Person God>}

Third, they're expandable by the developers. Each search extension can support its own syntax:

- {Label Journal Article WHERE Author ~ "F. F. Bruce" AND Date ~ <Date 1980>}

- {Label Figure of Speech WHERE Description ~ "Exchange of Cases" AND Name ~ "Antiptosis"}

For those of us (users) who don't (and shouldn't need to) understand the underworkings of the software, the distinction between <> and {} seem rather arbitrary.

I agree with this, and the honest answer is you don't need to understand it all, just like you don't need to understand how your car works to drive it.

But if you want to do complex searches (and we all do), then we need a relatively complex syntax. Simplifying that syntax would be a big mistake, because we'd gain nothing, just lose the ability to perform complex queries. (And we wouldn't gain the ability to perform simple queries, because we already have that. You can ignore { }, and even < >, and you have simple queries.)

That doesn't mean that search shouldn't be made easier. It should. But the way to make it easier is to allow users to construct complex searches without understanding how they work. As the developers have said, the right-click menu is a good way to do that now. A better way, which I'm hoping for in the future, would be a system which would present options for { searches whenever you typed { on the keyboard (in exactly the same way as @ does in a morph search). That would allow people to construct complex queries without having to remember a complex syntax.

First, let's talk about datatypes and datatype references on their own merits — irrespective of search syntax. That way, we won't muddy the waters.

Datatypes

We usually write datatypes between angle brackets, because that's how we search for them. But datatypes are used in other contexts without angle brackets, for example in specifying locations. For example, this is a link to the AYBD that uses the VolumePage datatype: https://ref.ly/logosres/anch;ref=VolumePage.V_1,_p_342

The help file says that a datatype is "A kind or family of information as distinct from other kinds of information. Each data type has its own internal rules and structure." There are hundreds of datatypes, and there can significant differences between datatypes:

- Some datatypes can only support a single value <PreachingTheme Adultery>, whilst others can support ranges <LN 96-97>.

- Some datatypes can have a hierarchy of values <Bible John>, <Bible John 3>, <Bible John 3:16>

- Some datatypes work in a fairly generic way, whilst others are quite specific. For example, Morph datatypes allow you to specify wildcards in a search, which most datatypes don't (<LogosMorphHeb ~ Va?1?????>).

So if datatypes vary so much, what do they have in common? They're all a way of storing arbitrary pieces of structured data within a resource.

Datatype reference

If a datatype is a specification of structured data, a datatype reference is an instance of structured data. So "Bible" is a datatype. "John 3:16" (internally "bible.64.3.16") is a datatype reference.

Most datatype references are hyperlinked, so that when you click on them another resource that supports that reference opens, according to your prioritisation. (Datatype references are one of two types of hyperlinks. The other type are simple links that go directly to a specific resource.)

But datatype references can be used in other contexts. For example, they're used in milestone indexes to specify locations within resources. They're also generated by tools like Factbook, of course.

Searching for datatype references

When a datatype reference is attached to text, we can search for it using the syntax <DataType Reference>. This search will only ever find occasions where the datatype reference is attached to text. (So searching for John 3:16, will find places where John 3:16 is referred to, but it won't find John 3:16 itself.)

Search extensions

The issue noted above was a problem in Logos 4. We could only search for datatype references when they were attached to text. For example, we couldn't search for datatype references in a milestone index. A milestone index is the index of locations in most resources. The index could be of volume/page numbers, bible references, or any other datatype. It's the inability to search in a milestone index that meant we couldn't find John 3:16 itself.

Theoretically, it would have been possible for Logos to extend search so that <John 3:16> found both references to John 3:16 in the text, and references to John 3:16 in milestone indexes. But then there would be no distinction. Perhaps we only want to find references to John 3:16 in the text, and aren't interested in milestones. Or the other way around.

In addition, users were clamouring for other ways of searching. Some people wanted to search within highlights.Other datasets were being developed, which marked arbitrary sections of text, and we'd want to search those too.

So Faithlife decided to introduce a new category of search, which they called search extensions, and these were indicated with curly braces.

There's a lot of variety in search extensions, but there are also important differences between search extensions and datatypes. The primary purpose of datatypes is to store structured data in a resource. Search is secondary. The primary purpose of search extensions is to extend search capability. That means that you search for datatype references, you search using search extensions.

A search extension will often allow you to specify datatype references in a special way. So searches such as {Milestone <Bible John 3:16>} allows you to search for any datatype that occurs in a milestone index. But {Highlight Yellow} has a difference specification. Then you're not searching for datatypes at all.

Extensions from Help documentation

- Independent

- Addressee

- Highlight

- PassageList

- Speaker

- Label

- Biblical annotation datasets

- Figurative Language

- Longacre Genre

- Interactive dataset labels

- Intertext

- Miracles

- Proverbs

- Psalm

- Other datasets

- Bible Books Supplemental Dataset

- Bullinger's Figures of Speech

- Propositional Outline

- Resource labels

- Bible Outline

- Journal Article

- Lectionary Reading

- Personal Letter

- Sermon

- Milestone

- finds citations; use resource information to identify relevant datatypes

- Section

- Culture

- Event

- Figurative language (FigLangCat, FigLangTerrn, FigLangType)

- Grammatical Constructions

- Literary Typing

- Preaching Theme (when applied to the Bible text)

- Sentence

- Speech Act

The fact that the Morris Proctor materials only show how to initiate the search from the right click menu and do not show the search itself does not help in making these searches approachable.

The fact that there are datasets for Speaking to God and Sacrifices but no documentation of a Search function does not help in making these searches approachable.

The fact that Help is inconsistent in providing the link to potential values does not help in making these searches approachable.

However, it does appear to be true that the search terms for extensions are always either a datatype or an attribute of a label so In that sense they do form a cohesive unit that requires that the user know only two pieces of information both of which are widely used in the application.

- { } items for which one provides the values of one or more attributes / datatypes in contrast to

- < > datatypes for which one supplies a value of the datatype itself in contrast to

- " " text which is itself the value in contrast to

- fields for which one provides no values or value of the field itself

The {Section syntax is not needed because the data is stored in a different place. (The search engine would be quite capable of retrieving data from all sorts of different places and merging it together.)

The {Section syntax is used because we're talking about a different kind of annotation. There are three primary ways we can categorise the relationship of text to a data type reference:

- the content of that reference, e.g., "In the beginning was the Word..." is the content of John 1:1. When you look up John 1:1, that's where you go.

- a reference to that reference, e.g., "see John 1:1". This is the most common use of data type references in the system, and what the syntax <John 1:1> searches for

- text about that reference, e.g., a commentary on John 1:1

In the early days of the Logos search engine, the second kind of annotation (reference) was the only thing you could search for, and what the search syntax was designed to enable.

It became clear that searching for milestones would be a useful enhancement, so we introduced the {Milestone syntax.

At the same time, we began realising that the third kind of annotation wasn't supported well in the Logos format. (That's the root cause of <PreachingTheme Wealth> being added (incorrectly, in my view) as a reference in the example I cited earlier: the right kind of tagging wasn't available to the resource owners. In fact, if I could turn back time, I probably wouldn't have Bible Commentaries tagged with Bible milestones—which constantly causes problems when unwary users prioritise them above their Bibles—but tagged as being about that verse. But it's a little late for that now.)

So when we started making supplemental data resources searchable, we also introduced the {Section search extension. Consider the "PreachingTheme Wealth" example. The text isn't a definition of the preaching theme (that would be in the Preaching Themes Glossary resource). It's also not an explicit reference to the theme (e.g., "see Wealth"). Rather, it's a biblical text or a sermon that's topically related to that preaching theme, or is a discussion of it. All these "related" or "about" texts can be found through {Section (if the appropriate datasets are in your system).

If we need to make more fine-grained distinctions about the relationship of the text to the data type reference it's being annotated with, we will create labels with specific properties and then you would have to use a {Label search to find them.

I should emphasise that due to the way things have developed over time, you can probably find many counterexamples of data being tagged as a reference where it shouldn't be, or being used inappropriately as a milestone, etc. Our ability to change these and standardise everything according to our current taxonomy is limited.

That doesn't negate the fundamental concept that there are distinct kinds of relationships between a section of text and a data type reference. These are encoded differently inside Logos resources, and the search engine surfaces that difference.

You search for datatype references, you search using search extensions.

I think this is a very helpful distinction.

You can even think of each search extension as being a "mini search engine" embedded inside the main Logos search engine.

That's why I keep saying "there's not a simple way to summarise them", each one is used for "other things", "there is no simple answer", etc.

A fourth way is for a word (or phrase) in a tagged text to be an instance or example of a classification. Lemmas, morphs, roots, senses, etc. all fall into this category. These are currently tagged as "references" (group #2 in my earlier post) in Logos, but are not hyperlinks.

If I accidentally included any statements above that were later corrected, please let me know.

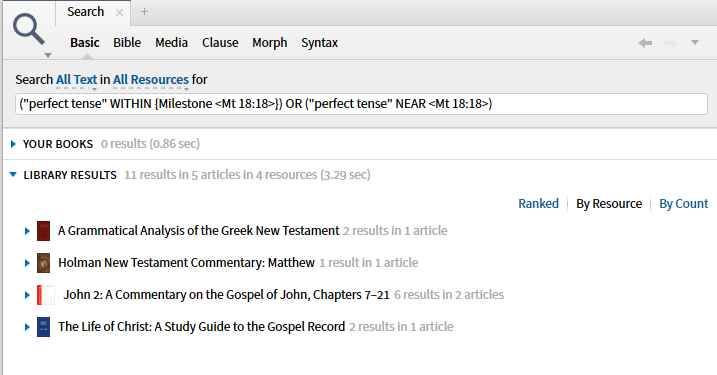

How do I search for discussions of the prefect tense in a particular verse?

Since Greek can be assumed with regards to that passage, and not all resources might use that full phrase, try the search: "perfect tense" WITHIN {Milestone <mt 18 18>}

You might also try the following search which may pick up a few additional relevant hits: "perfect tense" NEAR <mt 18 18>