Docx files for personal book: Verbum 9 part 1; Verbum 9 part 2; Verbum 9 part 3; Verbum 9 part 4; How to use the Verbum Lectionary and Missal; Verbum 8 tips 1-30; Verbum 8 tips 31-49

Reading lists: Catholic Bible Interpretation

Please be generous with your additional details, corrections, suggestions, and other feedback. This is being built in a .docx file for a PBB which will be shared periodically.

Previous post: Verbum Tip 6p Next post: Aside: Traditional Literary Criticism part 1

Aside: Traditional Literary Criticism

Questions Typically Asked

From Felix Just, S.J.:

- What words are used, and what range of meanings do they have?

- What images and symbols are used, and what do they signify?

- What characters appear in the story? What do we know about them? How are the characters related to one another in the story?

From Williamson, Peter. Catholic Principles for Interpreting Scripture: A Study of the Pontifical Biblical Commission’s The Interpretation of the Bible in the Church. Vol. 22. Subsidia Biblica. Roma: Pontificio Istituto Biblico, 2001.:

[quote]Principle #4

Because Scripture is the word of God that has been expressed in writing, philological and literary analysis are necessary in order to understand all the means biblical authors employed to communicate their message.

Philological and literary analysis contributes to determining authentic readings, understanding vocabulary and syntax, distinguishing textual units, identifying genres, analyzing sources, and recognizing internal coherence in texts (I.A.3.c). Often they make clear what the human author intended to communicate.

Literary analysis underscores the importance of reading the Bible synchronically (I.A.3.c; Conclusion c-d), of reading texts in their literary contexts, and of recognizing plurality of meaning in written texts (II.B.d)1.

Just as it makes use of history, Catholic exegesis makes use of the literary disciplines normally employed in the interpretation of written texts. This study refers to the totality of these disciplines under the heading, “philological and literary analysis”. Philological and literary analysis include morphology, syntax, historical philology, semantic analysis, and literary criticism2.[1]

From Tate, W. Randolph. Handbook for Biblical Interpretation: An Essential Guide to Methods, Terms, and Concepts. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2012.:

[quote]LITERARY CRITICISM

Criticism generally understood in three ways: (1) as source criticism, (2) as an explication of a text that attempts to understand the intention and accomplishment of the author by analyzing the compositional and structural elements of the text (see historical-critical method), and (3) as an approach that interprets the biblical texts as literature. The last approach is grounded in the assumption that the biblical authors were imaginative, creative crafters of art, employing structural elements and literary devices usually associated with the poetics of literature (i.e., the creation of literature) and genre.

Structural elements. Structural elements include the three basic components of literary texts: first, plot, with its five components of exposition, complication/rising action, climax, crisis, and resolution/denouement/falling action; second, setting, the time, the place, and all the objects included in the time and place; and third, characterization, the manner in which the various characters populating a text are portrayed either as rounded, static, dynamic, flat, full-fledged, or stereotypical. Other elements of structure are style, tone, atmosphere, point of view, syntax, and diction.

Literary devices. Literary devices at the disposal of authors are used to enhance the reading experience by engaging the reader in a variety of ways. Some of these devices will create informational gaps, or gaps of indeterminacy, that the reader must fill. For example, a metaphor asks the reader to make a comparison between two items (sometimes between two concrete items and sometimes between a concrete item and an abstract one). The author also creates a gap by alluding to another text, cultural object, or historical event or person (see allusion). By introducing a prior text, object, event, or person into a new context, the author expects the reader to glean the significance of the allusion. Other literary devices that authors regularly employ are simile, myth, hyperbole, symbol, understatement, synecdoche, parallelism, and personification. Rhetorical techniques usually fall under three general categories—ethos, pathos, and logos. (see rhetorical criticism for a discussion of these techniques.)

Genre. Another important issue within literary criticism is genre (see genre criticism). Literary critics generally assume that while texts may share common literary devices (listed in the previous paragraph), different types of texts operate according to different literary conventions. For example, readers generally do not expect to find complex plot development within poetry. Literary critics also claim that readers do not approach different types of texts in the same manner because they do not have the same expectations for every text. The readers of the bible do not approach a proverb with the same expectations as they would have for the book of Genesis. The literary critic approaches the pentateuch as theological history and the Proverbs as a collection of aphorisms. In the hebrew bible, the genres include theological history (e.g., the Pentateuch, deuteronomistic history, chronistic history), short story (e.g., Ruth, Jonah, Esther), prophecy (e.g., Isaiah, Jeremiah, Amos), and poetry (e.g., Psalms, Proverbs, Song of Songs). The latter genre, however, is complicated by the fact that there is poetry within most of the books of the Hebrew Bible, especially the prophetic books. Thus with the prophetic books, for example, the reader is faced with the responsibility of interfacing the genre conventions of both prophecy and poetry. The nt genres include gospel, apocalypse, and epistolary literature.

In addition to assumptions about structure, devices, and genre, literary critics also assume that any single text is a unified whole, in which the parts must be understood in terms of the whole and the whole in terms of the parts. This assumption is based on the prior assumption that authors select and arrange (see selection and arrangement) their materials according to a predetermined plan. Such a plan contributes to the possibility of the text’s being a unified whole and therefore its being read as an autonomous literary object. This is not to say that a literary text is univalent (see univalence), with a single determinant meaning. Indeed, the best pieces of literature are multivalent (see multivalence): they have the capacity to generate and legitimate a number of plausible understandings. Another way to put it is that great literature may have more than one theme and may encourage a number of inferences about those themes. Take the book of Jonah as an example. A reader might read the book of Jonah and see that God has done a supernatural thing in causing the great fish to swallow the prophet. From a modern scientific perspective, such a thing is impossible or at least improbable. Yet the reader might assume that this story teaches that natural laws and human possibilities do not bind God and that God will at times intervene in lives miraculously. This is a legitimate reading of Jonah. Reading the same book, another reader might notice that when Jonah decides to flee from God, he heads to Tarshish, which in ancient reckoning was a metaphor for paradise. This same reader might also notice that Jonah’s trek to what he thinks is paradise is actually a descent into death, denoted by a series of downward movements: Jonah goes down to Joppa, down into the belly of the ship, down into the belly of the fish, and down to Sheol. While Jonah thinks his flight is to paradise, his flight from God is actually a flight into death. Again, this reading is both suggested and legitimated by the text itself. Finally, a third reader may focus on Jonah’s actions at the end of the account. Jonah’s problem seems to be theological. Nineveh had perpetrated unspeakable atrocities on Jonah’s people and deserved judgment. But Jonah knows that a single act of repentance can erase a lifetime of sins. Jonah’s problem is that he does not want to live in a world where God’s grace is always poised to win out over justice. God is just, but God’s grace is always superabundant. Did the author intend for readers to arrive at all these possibilities? It is impossible to know for certain. The point is that a text such as Jonah and the others that we have looked at depend on readers to make sense of them, and this sense-making may be pluralistic.

Bibliography. John Hayes and Carl R. Holladay, Biblical Exegesis: A Beginner’s Handbook (Atlanta: John Knox, 1987); Richard N. Soulen and R. Kendall Soulen, Handbook of Biblical Criticism (3rd ed.; Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2001).[2]

While Verbum has some features that support literary criticism, its tools are more oriented to unambiguous equivalents rather than the fuzziness of similar to both.

Words

Verbum is strongly word oriented, to the point of providing disambiguation for parsing, words, antecedents, deixis, and senses. The primary tools are:

- Interlinears

- Bible sense lexicon

- Bible word study

The passage analysis tool contains two tools of use in word studies:

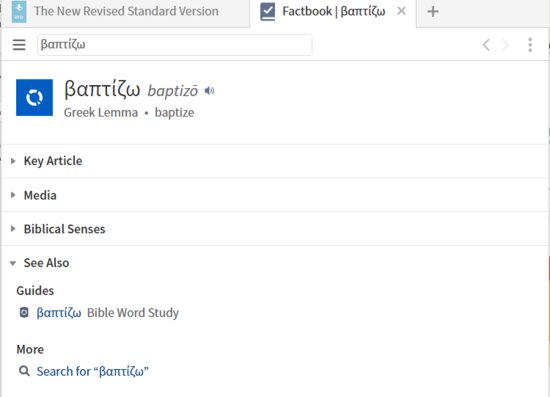

The new Factbook is adding some features of interest e.g.

- Lemma entries which rely on

- Brannan, Rick, ed. The Lexham Lexicon of the Aramaic Portions of the Hebrew Bible. Lexham Research Lexicons. Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2020.

- Brannan, Rick, ed. Lexham Research Lexicon of the Greek New Testament. Lexham Research Lexicons. Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2020.

- Brannan, Rick, ed. Lexham Research Lexicon of the Hebrew Bible. Lexham Research Lexicons. Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2020.

- Brannan, Rick, ed. Lexham Research Lexicon of the Septuagint. Lexham Research Lexicons. Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2020.

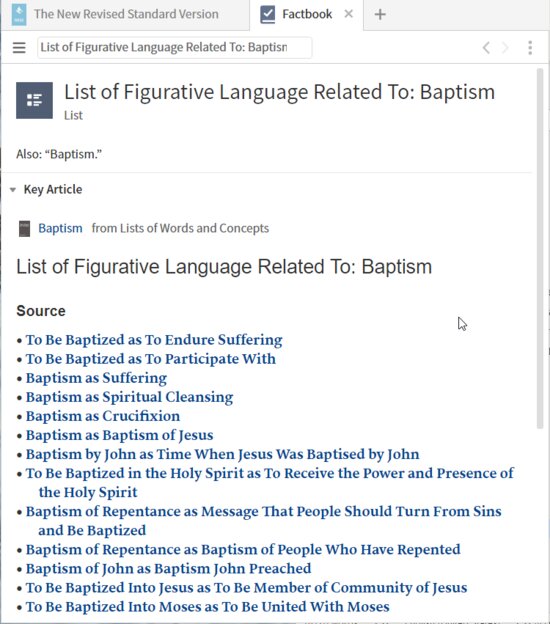

- Entries for List of Figurative Senses meaning <>

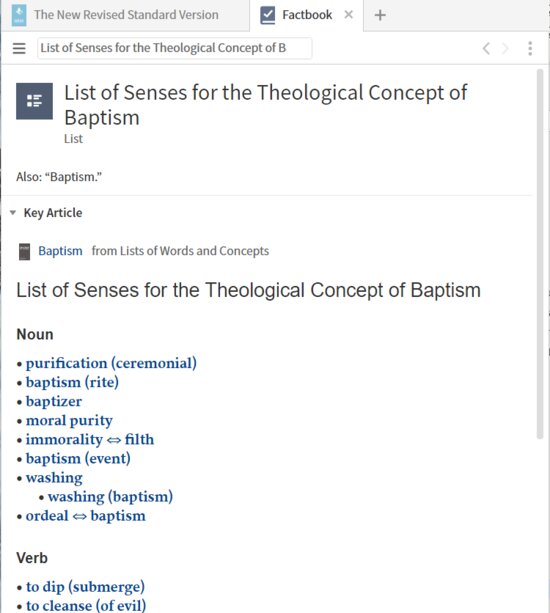

- Some entries for List of Senses for the Theological Concept of <>

- Entries for List of Biblical Things in the Domain of <>

Example for baptism:

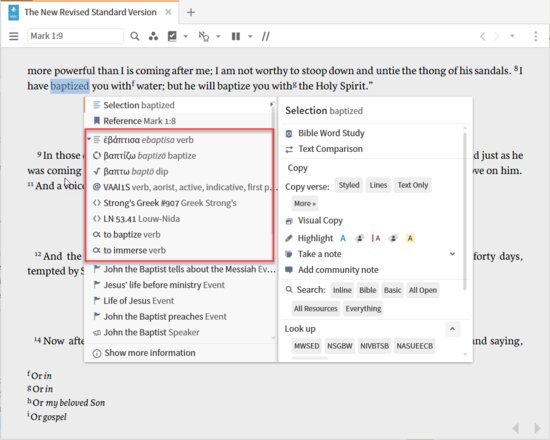

The word, its, morphology, lemma, sense, etc. all come through the interlinear. One can access, lexicons, Bible Sense Lexicon and Bible Word Study through the Context Menu.

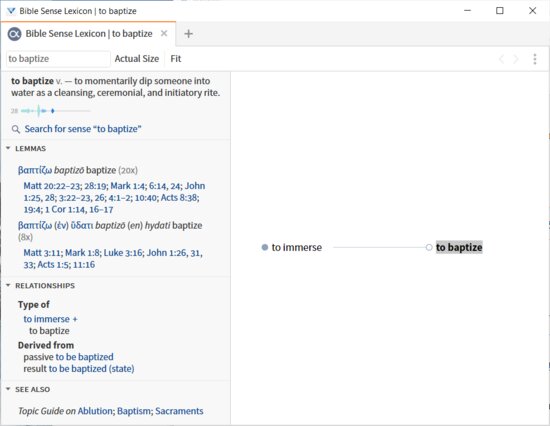

Bible Sense Lexicon

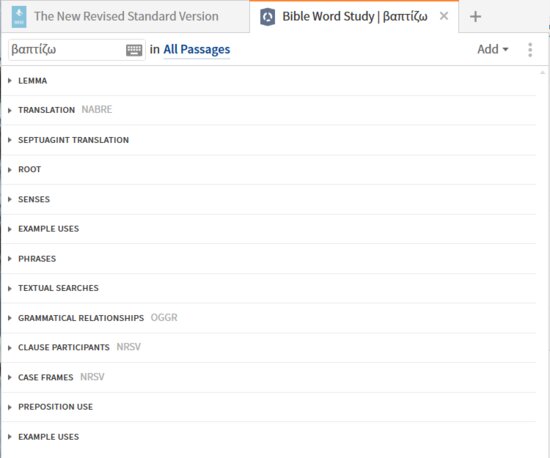

Bible Word Study

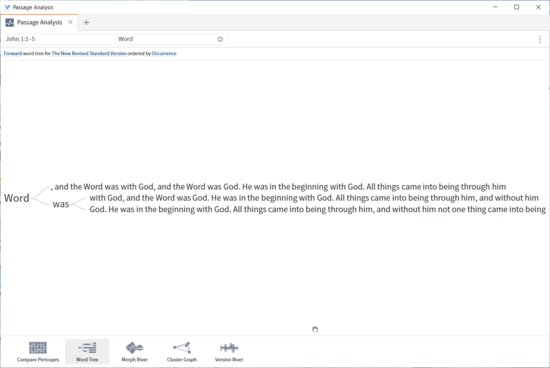

Word tree

Morph river

Factbook: lemma with key article from the Lexham Research Lexicon series provides the key articles.

Factbook: figurative senses

Factbook: senses

These tools should be used as the source of data and suggestions not as a definitive statement.

Images, symbols, types

On the figurative use of language – image, symbol, type, archetype, metaphor – Verbum has a Figurative Language data that is primarily oriented to contemporary linguistics and a Figure of Speech data that is based on Bullinger. Both of these are available through the Context Menu, the Information Panel, and a Search. Beyond that, Verbum simply provides access to relevant resources such as:

- Ryken, Leland, Jim Wilhoit, Tremper Longman, Colin Duriez, Douglas Penney, and Daniel G. Reid. Dictionary of Biblical Imagery. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2000.

- Ryken, Leland, Jim Wilhoit, Tremper Longman, Colin Duriez, Douglas Penney, and Daniel G. Reid. Dictionary of Biblical Imagery. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2000.

- Wilson, Neil, and Nancy Ryken Taylor. The A to Z Guide to Bible Signs and Symbols: Understanding Their Meaning and Significance. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 2015.

- Johnson, O. L. Bible Typology. James L. Fleming, 2005.

- Roza, Devin. Fulfilled in Christ: The Sacraments—A Guide to Symbols and Types in the Bible and Tradition. Bellingham, WA: Verbum, 2014.

- Bullinger, Ethelbert William. Figures of Speech Used in the Bible. London; New York: Eyre & Spottiswoode; E. & J. B. Young & Co., 1898.

I highly recommend this website be added to the shortcuts in the toolbar:

Conclusion “Conclusion” of The Interpretation of the biblic in the Church

1 The IBC indicates the importance of philological and literary analysis in its section on the historical-critical method (I.A), in a section devoted to literary methods (I.B), and in its discussion of the meanings of Scripture (II.B).

2 Here “literary criticism” is intended in the sense that term conveys in the study of “secular” literature; it now also describes an aspect of the literary analysis of the Bible. The problem is that in biblical studies “literary criticism” has referred to what is better named “source criticism”. This study will try to make clear by the context which of the two senses is intended.

[1] Peter Williamson, Catholic Principles for Interpreting Scripture: A Study of the Pontifical Biblical Commission’s The Interpretation of the Bible in the Church, vol. 22, Subsidia Biblica (Roma: Pontificio Istituto Biblico, 2001), 65–66.

[2] W. Randolph Tate, Handbook for Biblical Interpretation: An Essential Guide to Methods, Terms, and Concepts (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2012), 240–242.