Docx files for personal book: Verbum 9 part 1; Verbum 9 part 2; Verbum 9 part 3; Verbum 9 part 4; Verbum 9 part 5; How to use the Verbum Lectionary and Missal; Verbum 8 tips 1-30; Verbum 8 tips 31-49

Reading lists: Catholic Bible Interpretation

Please be generous with your additional details, corrections, suggestions, and other feedback. This is being built in a .docx file for a PBB which will be shared periodically.

Previous post: Verbum Tip 7x Next post: Aside: Comparison translations part 2

Aside: Comparison of Translations

Questions Typically Asked

From Felix Just, S.J.:[quote]

- Are there any significant differences between various modern translations?

- When were these translations done, using which translation philosophies?

- Which ancient Hebrew or Greek texts underlie the various translations?

- Has anything been lost or obscured in the process of translation?

To put a translation of scripture into the appropriate context, The Interpretation of the Bible in the Church addresses translations under the topic of inculturation:[quote]

While actualization allows the Bible to remain fruitful at different periods, inculturation in a corresponding way looks to the diversity of place: It ensures that the biblical message takes root in a great variety of terrains. This diversity is, to be sure, never total. Every authentic culture is, in fact, in its own way the bearer of universal values established by God.

The theological foundation of inculturation is the conviction of faith that the word of God transcends the cultures in which it has found expression and has the capability of being spread in other cultures, in such a way as to be able to reach all human beings in the cultural context in which they live. This conviction springs from the Bible itself, which, right from the book of Genesis, adopts a universalist stance (Gn. 1:27–28), maintains it subsequently in the blessing promised to all peoples through Abraham and his offspring (Gn. 12:3; 18:18) and confirms it definitively in extending to “all nations” the proclamation of the Christian Gospel (Mt. 28:18–20; Rom. 4:16–17; Eph. 3:6).

The first stage of inculturation consists in translating the inspired Scripture into another language. This step was taken already in the Old Testament period, when the Hebrew text of the Bible was translated orally into Aramaic (Neh. 8:8, 12) and later in written form into Greek. A translation, of course, is always more than a simple transcription of the original text. The passage from one language to another necessarily involves a change of cultural context: Concepts are not identical and symbols have a different meaning, for they come up against other traditions of thought and other ways of life.

Written in Greek, the New Testament is characterized in its entirety by a dynamic of inculturation. In its transposition of the Palestinian message of Jesus into Judeo-Hellenistic culture it displays its intention to transcend the limits of a single cultural world.

While it may constitute the basic step, the translation of biblical texts cannot, however, ensure by itself a thorough inculturation. Translation has to be followed by interpretation, which should set the biblical message in more explicit relationship with the ways of feeling, thinking, living and self-expression which are proper to the local culture. From interpretation, one passes then to other stages of inculturation, which lead to the formation of a local Christian culture, extending to all aspects of life (prayer, work, social life, customs, legislation, arts and sciences, philosophical and theological reflection). The word of God is, in effect, a seed, which extracts from the earth in which it is planted the elements which are useful for its growth and fruitfulness (cf. Ad Gentes, 22). As a consequence, Christians must try to discern “what riches God, in his generosity, has bestowed on the nations; at the same time they should try to shed the light of the Gospel on these treasures, to set them free and bring them under the dominion of God the Savior” (Ad Gentes, 11).

This is not, as is clear, a one-way process; it involves “mutual enrichment.” On the one hand, the treasures contained in diverse cultures allow the word of God to produce new fruits and on the other hand, the light of the word allows for a certain selectivity with respect to what cultures have to offer: Harmful elements can be left aside and the development of valuable ones encouraged. Total fidelity to the person of Christ, to the dynamic of his paschal mystery and to his love for the church make it possible to avoid two false solutions: a superficial “adaptation” of the message, on the one hand, and a syncretistic confusion, on the other (Ad Gentes, 22).

Inculturation of the Bible has been carried out from the first centuries, both in the Christian East and in the Christian West, and it has proved very fruitful. However, one can never consider it a task achieved. It must be taken up again and again, in relationship to the way in which cultures continue to evolve. In countries of more recent evangelization, the problem arises in somewhat different terms. Missionaries, in fact, cannot help bring the word of God in the form in which it has been inculturated in their own country of origin. New local churches have to make every effort to convert this foreign form of biblical inculturation into another form more closely corresponding to the culture of their own land.[1]

Many of us think of inculturation as applying to others – Africans, Asians, tribal groups – forgetting that our own culture is equally distance from the world of the Biblical authors.

The same source emphasizes the need for ecumenical versions of the Bible:[quote]

Since the Bible is the common basis of the rule of faith, the ecumenical imperative urgently summons all Christians to a rereading of the inspired text, in docility to the Holy Spirit, in charity, sincerity and humility; it calls upon all to meditate on these texts and to live them in such a way as to achieve conversion of heart and sanctity of life. These two qualities, when united with prayer for the unity of Christians, constitute the soul of the entire ecumenical movement (cf. Unitatis Redintegratio, No. 8). To achieve this goal, it is necessary to make the acquiring of a Bible something within the reach of as many Christians as possible, to encourage ecumenical translations--since having a common text greatly assists reading and understanding together--and also ecumenical prayer groups, in order to contribute, by an authentic and living witness, to the achievement of unity within diversity (cf. Rom. 12:4-5).

Verbum supports the comparison of version by providing a variety of translations in a variety of languages. It also provides a variety of tools to assist in the identification of differences in translations, identification of the cause of the differences, the identification of patterns of variation . . .

A small bit on Eugene Nida on translation from Wikipedia:[quote]

His most notable contribution to translation theory is Dynamic Equivalence, also known as Functional Equivalence. . . . Nida also developed the componential analysis technique, which split words into their components to help determine equivalence in translation (e.g. "bachelor" = male + unmarried). This is, perhaps, not the best example of the technique, though it is the most well-known.

. . .

Nida then sets forth three factors that must be taken into account in translating:

- The nature of the message: in some messages the content is of primary consideration, and in others the form must be given a higher priority.

- The purpose of the author and of the translator: to give information on both form and content; to aim at full intelligibility of the reader so he/she may understand the full implications of the message; for imperative purposes that aim at not just understanding the translation but also at ensuring no misunderstanding of the translation.

- The type of audience: prospective audiences differ both in decoding ability and in potential interest.

While reminding that while there are no such things as "identical equivalents" in translating, Nida asserts that a translator must find the "closest natural equivalent." Here he distinguishes between two approaches to the translation task and types of translation: Formal Equivalence (F-E) and Dynamic Equivalence (D-E).

F-E focuses attention on the message itself, in both form and content. Such translations then would be concerned with such correspondences as poetry to poetry, sentence to sentence, and concept to concept. Such a formal orientation that typifies this type of structural equivalence is called a "gloss translation" in which the translator aims at reproducing as literally and meaningfully as possible the form and content of the original.

The principles governing an F-E translation would then be: reproduction of grammatical units; consistency in word usage; and meanings in terms of the source context.

D-E on the other hand aims at complete "naturalness" of expression. A D-E translation is directed primarily towards equivalence of response rather than equivalence of form. The relationship between the target language receptor and message should be substantially the same as that which existed between the original (source language) receptors and the message.

The principles governing a D-E translation then would be: conformance of a translation to the receptor language and culture as a whole; and the translation must be in accordance with the context of the message which involves the stylistic selection and arrangement of message constituents.[2]

Bibliography on translation comparison

Multiple versions

Verbum offers many Bibles that may be read in parallel. Common sets to compare depend upon your interests and library. Suggestions to consider:

- Translations by manuscript traditions: one translation representing Masoretic, Targum, LXX, Peshitta, Vulgate, Textus Receptus, Patriarchal, and Critical

- Translations in English representing various periods in the development of the English language

- Translations approved by the appropriate ecclesial entity

- Translations approved for use in worship around the world

- Translations academics suggest for exegesis

- Translations used most in ecumenical settings

- Catholic translations – historical and current

- Personal favorites

Link set

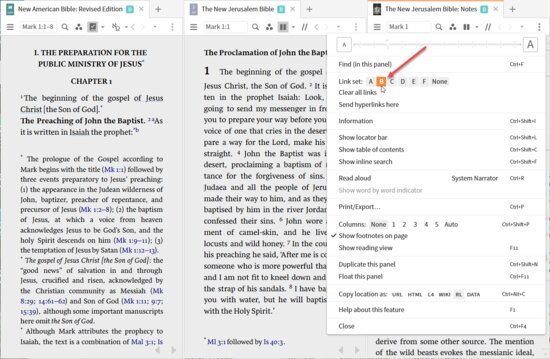

From Verbum Help’s discussion of the panel menu:[quote]

• Link set — Resources that are indexed by the same data type can be linked together, and set to navigate to the same reference at the same time.

• Clear all links — Clears all Link sets in the relevant resources at once.[3]

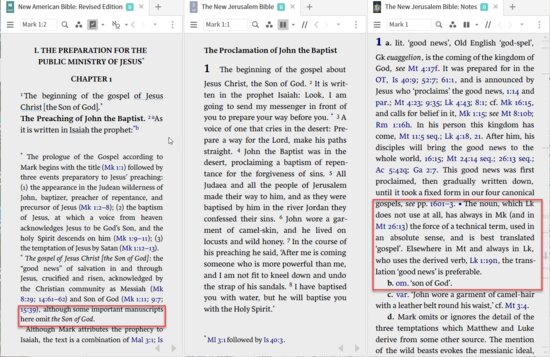

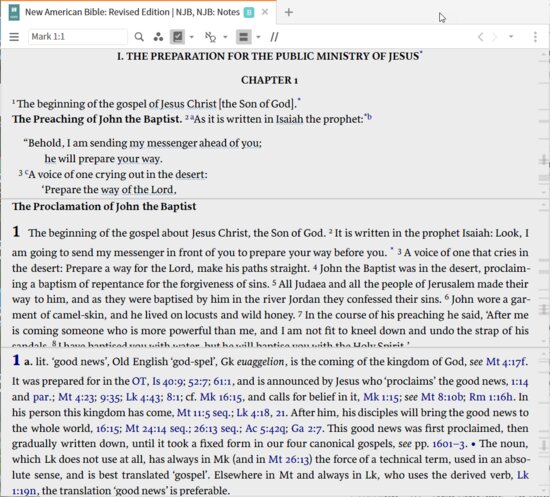

This screen illustrates:

- The use of a link-set (B) to keep the Bibles aligned with each other. Select link set B in the final resource to complete the linkage.

- The displaying of the footnotes at the bottom of the page.

- The unusual situation of the footnotes being an independent resource.

This approach places the responsibility for comparison directly on the reader. However, the footnotes often show alternative readings or explain the translator’s choice.

Multiple resources panel

From Verbum Help:[quote]

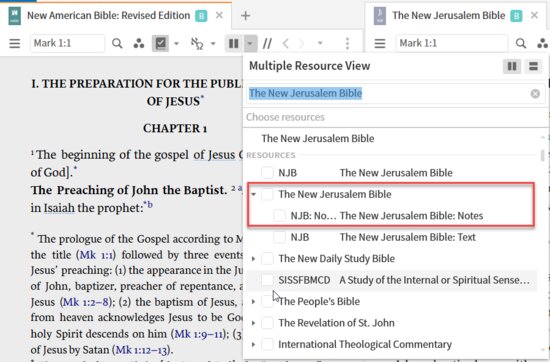

Multiple Resources

The Multiple Resources feature provides additional "guest" resources in the same panel as the main "host" resource. This functions similarly to having multiple resource panes open connected with a link set, with some differences and advantages.

Any number of resources can be added as guests, and guest resources share several of the traits of a host resource automatically. Visual Filters, Inline Interlinears, and Inline Searches will all be applied to applicable guest resources.

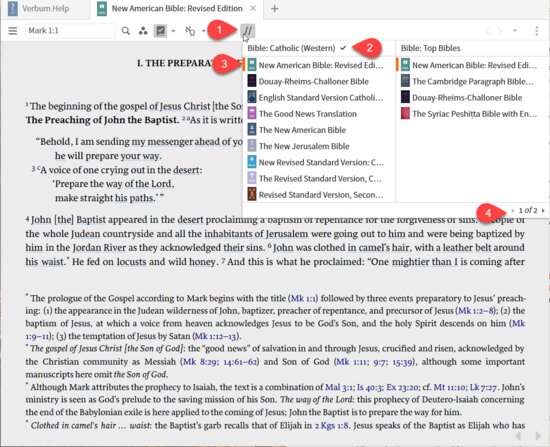

Accessing the Multiple Resources feature

The feature is only accessible in resources that contain Bible milestones; in general, this means Bibles, Bible Commentaries, original language fragments, etc. Add the Multiple Resources menu to a Bible by clicking the icon on the resource toolbar. The Multiple Resources option can be enabled and disabled after adding guest resources by clicking again, or by pressing Cmd+Shift+M (Mac) / Ctrl+Shift+M (Windows).

Adding guest resources

Click to open the Multiple Resources drop-down menu. Enter a book’s full title, or short title, and matches will be promoted to the top of the list for easy access. For example, to add the New International Version (2011) as a guest resource, type New International or NIV and that Bible will appear at the top of the list.

To add the desired resource to the panel, click the checkbox next to the resource name. It will go to the upper section of the menu, which will populate with all added resources.

At the very top of the Multiple Resources menu, click the checkbox next to Show multiple resources: to enable and disable the feature while maintaining the list of desired resources. This is the same behavior as using the above keyboard shortcuts for toggling the feature.[4]

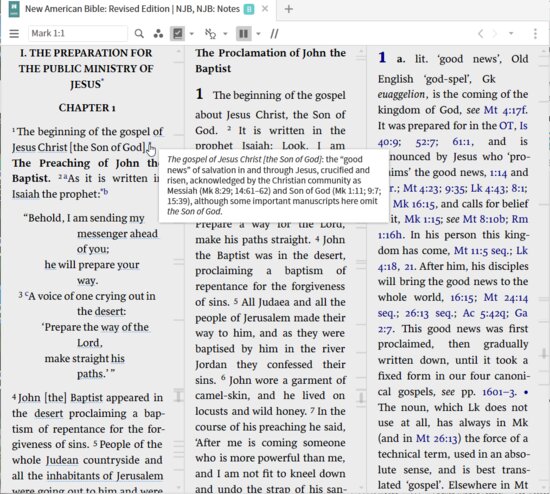

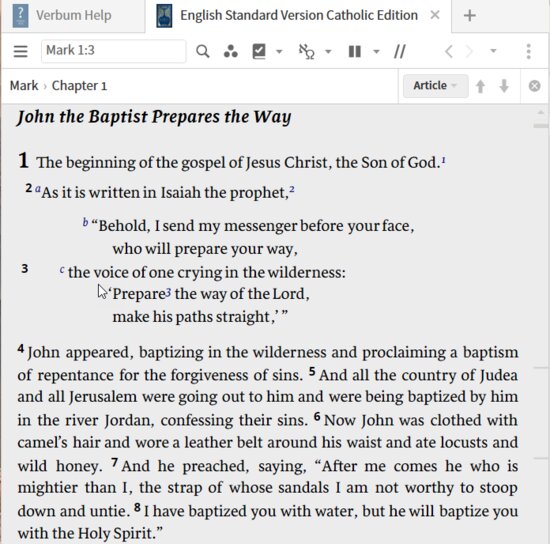

In this view you must navigate in the NABRE for the other resources to follow. This contrasts with the link set when navigating in any resource causes the other to follow.

Setting up the multiple resource panel:

The same three resources shown for a link set as a vertical multiple resource panel. Note that it is in scroll rather than page mode. Therefore, one must use the mouse to see the notes and footnotes in the NABRE.

The same limitations hold for the horizontal view:

Parallel resources

From Verbum Help:[quote]

Parallel Resource Sets

Choose which set of resources will be accessible when using left and right arrow buttons or keys to view Parallel esources.

To view Parallel Resource sets:

• Open the Parallel Resource sets dropdown by clicking on the resource toolbar.

• Select the pre-built All parallel sets, or a user-defined collection (see Note below), by clicking the corresponding column header. The checkmark will switch to the active collection

• Click a resource in the drop-down list to open that resource directly.

• To edit a collection, right-click the title and choose Edit [collection] to open it in the Collections panel.

• To remove a collection from the list of Parallel esource sets, right-click the title and choose Remove collection from list. The collection can be added again by checking the Show in Parallel esources box in the collection’s edit window.

Note: collections must have the Show in Parallel esources box checked to be listed on the dropdown.[5]

And for navigation:[quote]

• Ctrl+right arrow – Navigate to next parallel resource (use this if current resource has a horizontal scrollbar)

• Ctrl+left arrow – Navigate to previous parallel resource (use this if current resource has a horizontal scrollbar)

• Right arrow – Navigate to next parallel resource

• Left arrow – Navigate to previous parallel resource[7]

To set a resource up for parallel resources – a system generated list or a collection. As you use the arrows to navigate, the resources will stay aligned.

- Select the parallel resources icon

- Note the check mark beside the currently active parallel resources list. If you click on the title of another list, the active list checkmark will move to that list.

- Note the orange bar showing the currently active resource.

- Note the possibility of multiple pages.

Note that there is no indication on the tab that the resource has parallel resources set. Just try navigation via the arrow keys.

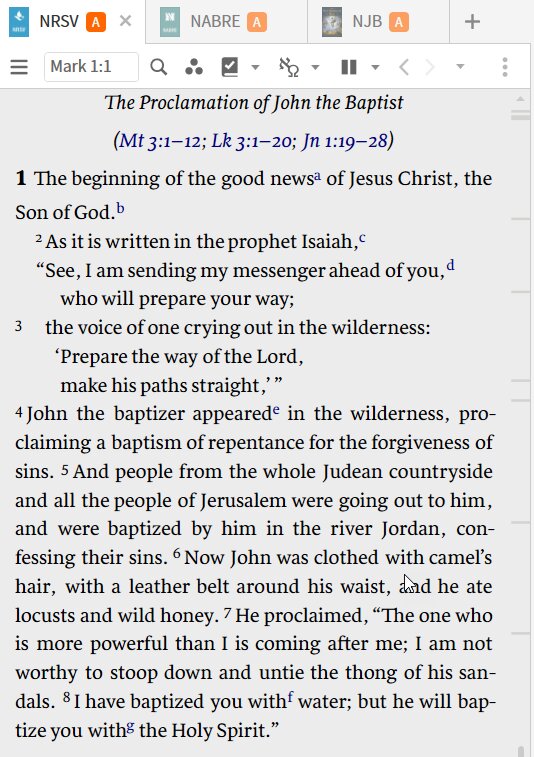

Multiple tabs

This option is often used in the predefined layouts. It combines a linked set contained within a single pane with keyboard navigation.

From Verbum Help:[quote]

• Ctrl+Page Up – Switch to previous tab

• Ctrl+Page Down – Switch to next tab

[1] Pontifical Biblical Commission, The Interpretation of the Bible in the Church (Vatican City: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 1993).

[2] Eugene Nida - Wikipedia accessed 4/10/2021 3:24 PM

[3] Verbum Help (Bellingham, WA: Faithlife, 2018).

[4] Verbum Help (Bellingham, WA: Faithlife, 2018).

[5] Verbum Help (Bellingham, WA: Faithlife, 2018).

Verbum Help (Bellingham, WA: Faithlife, 2018).

Verbum Help (Bellingham, WA: Faithlife, 2018).

[7] Verbum Help (Bellingham, WA: Faithlife, 2018).

Verbum Help (Bellingham, WA: Faithlife, 2018).

Verbum Help (Bellingham, WA: Faithlife, 2018).