Docx files for personal book: Verbum 9 part 1; Verbum 9 part 2; Verbum 9 part 3; Verbum 9 part 4; Verbum 9 part 5; Verbum 9 part 6; How to use the Verbum Lectionary and Missal; Verbum 8 tips 1-30; Verbum 8 tips 31-49

Reading lists: Catholic Bible Interpretation

Please be generous with your additional details, corrections, suggestions, and other feedback. This is being built in a .docx file for a PBB which will be shared periodically.

Previous post: Verbum Tip 8al Next post: Aside: Forum tidbits

Aside: Catholic Bible Interpretation - Textual Criticism

Questions Typically Asked

From Felix Just, S.J.:

- Are there any variant readings in the ancient manuscripts?

- Are the variants negligible (mere spelling) or significant (affecting meaning)?

- Can the variants be explained as intentional changes, or as accidental ones?

- How do the literary or historical contexts help explain the variant readings?

Textual criticism is a specialty that requires fluency in the language of the text, knowledge of the development/history of the scripts used to write the text, familiarity with writing materials as another element to date the text . . . and access to the original manuscripts or high definition facsimiles of them.

[quote]TEXTUAL CRITICISM

A criticism whose primary task is to compare the many biblical manuscripts and manuscript families in order to produce a Greek or hebrew version that most closely approximates the original. Its aim is threefold: (1) to determine the transmission process of a text and the reason it exists in variant forms; (2) to determine the original wording if possible; and (3) to produce a reliable Greek or Hebrew text.

None of the autographs of the biblical texts survive, only copies of copies, the earliest for the hebrew bible dating from the seventh century bce (if one includes some short fragments of text) and, for the nt, from the second century ce. Since the available copies were handwritten by scribes and because there exists a gap between the originals and the earliest copies, textual critics cannot assume with complete certainty that they have recovered the original wording of the biblical texts.

Since the thousands of manuscripts (from complete texts to fragments) exist in various translations (Greek, Latin, Syriac, Coptic) and in quotations in other kinds of texts, there are four broad categories of variants: (1) between manuscripts in the original languages; (2) between manuscripts in early translations; (3) between ancient manuscripts in the original languages and early translations; and (4) between quotations in early Jewish and Christian writings. But variants may also be intentional or unintentional. Intentional variants appear when scribes changed the wording of the text. The wording could be changed in order to correct a perceived spelling or grammatical error. Scribes also made changes in syntax, rearranging the word order and sentence and paragraph structure. Additions, omissions, changes, transpositions, and glosses were made in order to improve the text. Scribes also introduced theological and doctrinal changes to make the text conform to a more orthodox position. Substitutions were sometimes made to remove what might seem to a scribe to be offensive material. Regardless of the type of intentional changes made, textual critics usually assume that the intention of the scribes was to improve the text.

Unintentional variants are usually those resulting from sight or hearing. Copying errors occurred when the scribe would look at the manuscript and then attempt to copy from it. For example, the scribe might skip a word or line, write a word or line twice, misspell a word, reverse the order of letters within a word, or confuse the order of words within a sentence. When a number of scribes were making copies while listening to a reader of a manuscript, errors of hearing were possible. A scribe might not hear the word or group of sentences correctly or might not write correctly what he did hear. Sometimes scribes would make notes or glosses in the margins of texts, and then years later these might be taken as part of the texts and incorporated into new manuscripts by copyists. However, many ot textual critics doubt the “errors of hearing” problem.

With all the possible variants, how do textual critics determine the most plausible version? Generally, critics rely on two types of evidence: internal and external. As the term suggests, internal evidence arises from within the text itself. Since textual critics are familiar with the process by which ancient texts were composed, copied, preserved, and transmitted, they have identified the types of variants and the reasons they occur. Consequently, in trying to establish the most plausible version, textual critics simply work backward from the variants toward the original. First, on the assumption that scribes tended to correct or smooth out difficulties, textual critics claim that when one is choosing between variants, the more difficult reading is to be preferred. Second, because scribes tended to expand texts rather than delete elements from them, the shorter reading is probably closer to the original. Third, since copyists tended to harmonize different versions of the same text, versions that seem to be harmonistic are rejected in favor of a more dissonant one. Fourth, when variant readings seem not to conform to an author’s style, tone, or vocabulary within the same document or in other texts, textual critics generally reject these as inauthentic.

External evidence includes considerations outside the text, such as the date and nature of the manuscripts, the geographical locations of the manuscripts, and the relationship between families of texts. As the biblical writings began to spread throughout the Mediterranean world, certain cities became what critics call “homes” of versions of texts and textual traditions. In other words, in places such as Rome, Alexandria, and Constantinople, certain definable textual traditions arose. Textual critics have assigned the various nt and lxx versions to families or recensions based on their similarities and identification with geographical areas. Furthermore, textual critics have discovered that some families of texts tend to expand the material when compared with other groups. So if the critic is weighing the external evidence between a version where one group of manuscript witnesses reveals an expansionist tendency while another one does not, the textual critic will generally choose the latter reading. A second external piece of evidence is the date of the manuscript witnesses. Generally, the critic will assume that the earlier version is more likely to be authentic. A third point of external evidence is that manuscript witnesses are weighed rather than counted. For example, it is possible for one reading to be found in a number of fifth-century witnesses but another reading in a single tenth-century witness that better satisfies the components of internal evidence. Therefore, the textual critic would choose the single tenth-century witness as the more authentic one.

Critical editions of the nt and the Hebrew Bible are in the original languages and contain a critical apparatus, an extensive set of footnotes that list variants and the ancient sources (manuscripts, translations, versions, commentaries, quotations) in which the variants occur. Some critical editions include only some of the variants; others list every variant within a text. Although modern translations do not have a critical apparatus, those that are committee translations are based on serious attention to the apparatus of the critical editions. They sometimes offer footnotes that indicate the most crucial variants and include abbreviated information on the type of variant (addition, omission, etc.).

Once the critic has accumulated both internal and external evidence, the critic makes a decision as to which reading best approximates the original. Since no originals are extant, textual criticism depends on the available evidence and the informed judgment of the critic. For an excellent introduction to textual criticism, see Voelz.

Bibliography. J. Harold Greenlee, Introduction to New Testament Textual Criticism (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1964; rev. ed., Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1995); John H. Hayes and Carl R. Holladay, Biblical Exegesis: A Beginner’s Handbook (Atlanta: John Knox, 1987); Ralph W. Klein, Textual Criticism of the Old Testament (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1974); Charles B. Puskas, An Introduction to the New Testament (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1989); Emanuel Tov, Textual Criticism of the Hebrew Bible (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1992); James W. Voelz, What Does This Mean? Principles of Biblical Interpretation in the Post-modern World (St. Louis: Concordia, 1995).[1]

Note that computer analysis of texts is quickly changing the field through the increased ability to compare large numbers of the available texts.

For the rest of us, Verbum supplies access to the manuscripts either within Verbum as transcriptions or externally on the internet through the Manuscript Explorer Interactives. Verbum also provides several apparatuses that expand on the critical texts. Apparatuses are:

[quote]CRITICAL APPARATUS

In Hebrew and Greek editions of the hebrew bible and the nt, an extensive set of footnotes listing variant readings and the ancient sources (manuscripts, translations, versions, commentaries [see commentary], quotations, lectionaries [see lectionary], and church fathers) in which the variants occur. Most critical editions include only some of the variant readings, while a few others list every variant within a text. Although modern translations do not have a critical apparatus, those that are committee translations are based on serious attention to the critical apparatuses of the critical editions. They offer footnotes that indicate the most crucial variants and include abbreviated information on the type of variant (addition, omission, etc.). See critical text.[2]

Our commentaries are dependent upon the results of textual criticism leaving most of us very familiar with textual criticism without knowing the standard name for the discipline behind it (marked in bold.)

[quote]

Verse 1*, beginning “The words of Jeremiah,” followed by his lineage, matches most closely Amos 1:1*, “The words of Amos, who was among the shepherds of Tekoa….” Verse 2*, however, is a different matter. The sequence is אֲשֶׁר הָיָה דְבַר־יהוה אֵלָיו בִּימֵי…; its syntax is unclear. It is closely analogous to the headings of 14:1*; 46:1*; 47:1*; and 49:34*: all of these read אֲשֶׁר הָיָה דְבַר־יהוה אֶל־יִרְמְיָהוּ, and these are independent clauses, evidently to be translated “What has come as the word of Yahweh to Jeremiah”—peculiar as the syntax is, it is evidently not a reading due to scribal error2 but a form peculiar to the Book of Jer. [3]

The Greek nouns theos and kyrios are both without the article. This has led some scholars to see the phrase as referring solely to Jesus: “Jesus Christ, God and Lord” (e.g., Vouga, “Jésus-Christ, Dieu et Seigneur,” 35). For Jesus to be described in such an unequivocal way as God would be extremely unusual in the context of the New Testament writings, especially if the letter of James is judged to be a relatively early writing (see the Introduction). Some manuscripts try to remove the ambiguity by identifying God as “Father” (patēr). This is clearly not the original text, but an interpretation. James is a slave both of God (as Father) and Jesus (as Lord), which implies an equality between God (as Father) and Jesus (as Lord), but their exact relationship is not discussed in any depth. In calling Jesus “Lord” James reflects a practice found in very early Christian liturgical texts: “Come, Lord Jesus!” (Rev 22:20) and “Our Lord, come!” (1 Cor 16:22). [4]

Psalms 9–10 show traces of an acrostic scheme of ascending letters of the Hebrew alphabet,7 and the fact that Psalm 10 has no caption argues in favor of this. Psalms 3–9 and 11–32 all have captions, which make the void in Psalm 10 stand out. The text is badly preserved, which accounts for the conjectured translations particularly in the l, m, n, s, and ṣ lines, around the juncture of the two psalms. The general call for help changes to an urgent personal appeal at the center (the middle letter lāmed), with the plaintive tone, “Why, O Lord, do you stand far off? Why do you hide yourself in times of trouble?” (10:1). Such a change of tone is not unusual in an acrostic (for example, Ps 34:11). The repeated invocation to “Rise up, O Lord” also unifies the composition (9:19; 10:12).[5]

What apparatus should I learn to read?

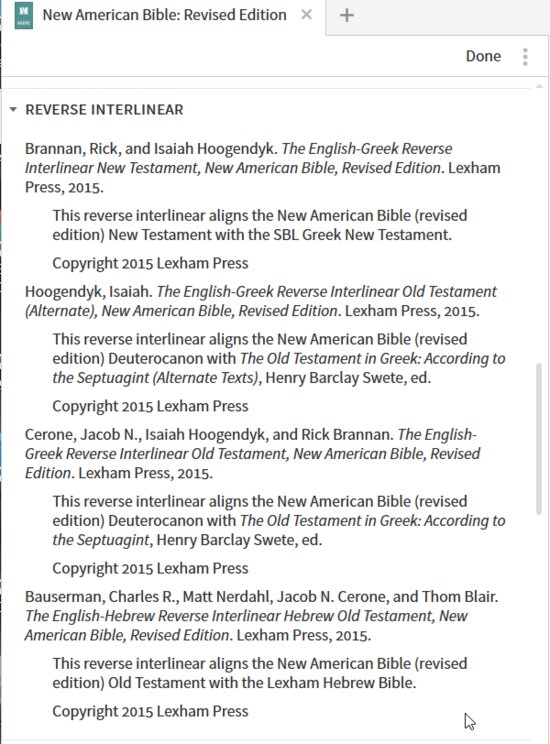

First, I will assume that if you are fluent in the original languages, you are already comfortable with critical editions, apparatuses, and notes. For the rest of us, we start with the reverse interlinear. To find the critical editions used for the NABRE reverse interlinear:

- Select the panel menu

- Select information

- Scroll down to expand reverse interlinear

|

|

Critical text

|

Apparatus

|

Notes

|

|

NABRE NT

|

Holmes, Michael W. The Greek New Testament: SBL Edition. Lexham Press; Society of Biblical Literature, 2011–2013.

|

Holmes, Michael W. Apparatus for the Greek New Testament: SBL Edition. Logos Bible Software, 2010.

|

Brannan, Rick, and Israel Loken. The Lexham Textual Notes on the Bible. Lexham Bible Reference Series. Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2014.

|

|

NABRE GK OT

|

Swete, Henry Barclay. The Old Testament in Greek: According to the Septuagint. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1909.

|

Swete, Henry Barclay. The Old Testament in Greek: According to the Septuagint (Apparatus). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1909.

|

n/a

|

|

NABRE GK OT ALT

|

Swete, Henry Barclay. The Old Testament in Greek: According to the Septuagint (Alternative Texts). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1909.

|

Swete, Henry Barclay. The Old Testament in Greek: According to the Septuagint (Apparatus Alternative). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1909.

|

n/a

|

|

NABRE HEB OT

|

The Lexham Hebrew Bible. Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2012.

|

n/a

(Weil, Gérard E., K. Elliger, and W. Rudolph, Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft. Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia. 5. Aufl., rev. Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 1997. Is likely the most useful).

|

Brannan, Rick, and Israel Loken. The Lexham Textual Notes on the Bible. Lexham Bible Reference Series. Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2014.

|

Unfortunately, the symbols and data tagged is inconsistent among apparatuses. You need to check the sigla, abbreviations and legend for each apparatus before using it.

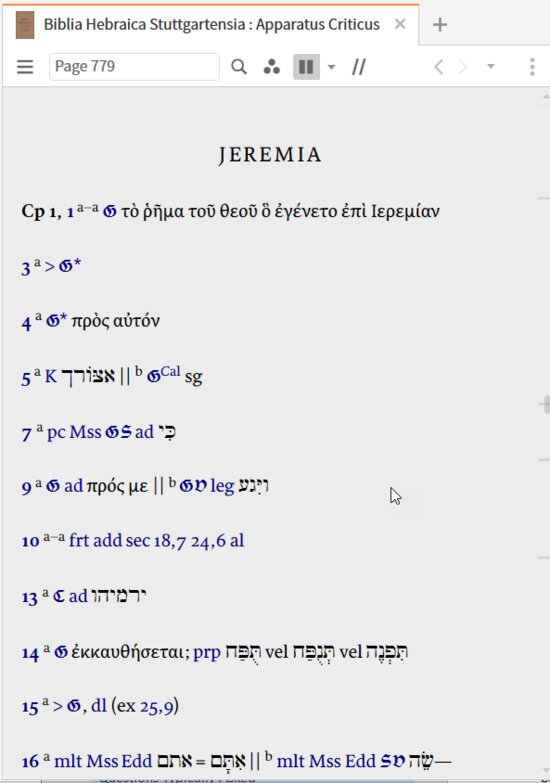

Example: BHS

The BHS offers two resources to learn to use the critical apparatus:

- HEBSTGD007.pdf (bethel.edu) which I have had for so long as a personal book that I keep forgetting that it is not a Verbum resource

- Wonneberger, Reinhard. Understanding BHS: A Manual for the Users of Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia. 2nd rev. ed. Vol. 8. Subsidia Biblica. Roma: Pontificio Istituto Biblico, 1990.

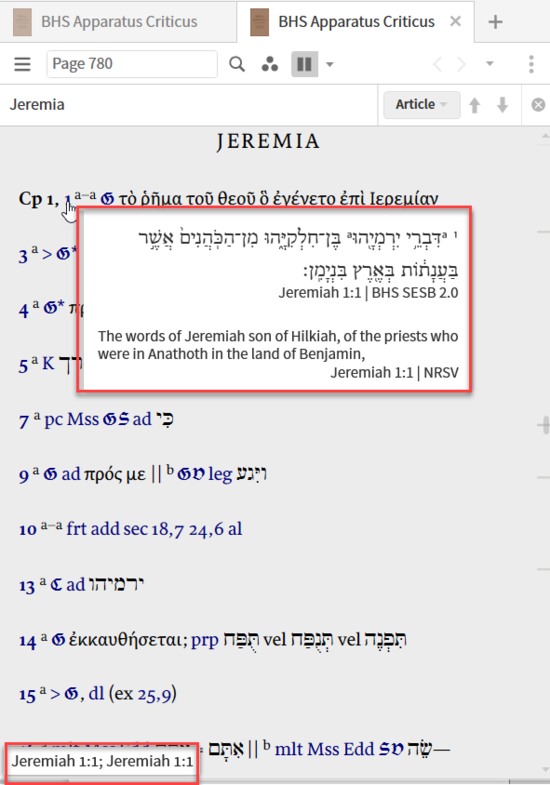

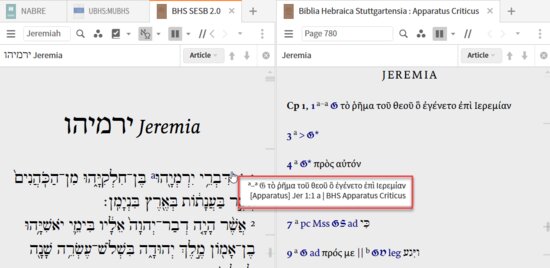

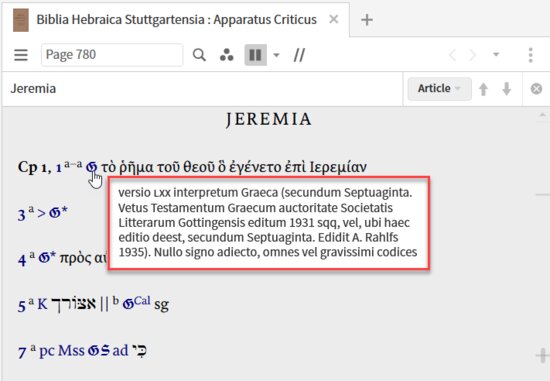

For the Jeremiah quoted above, the apparatus has:

Yes, it looks like obscure code and it refers to the Greek LXX as well as the Hebrew.

Cp has no mouse-over interpretation. I’ll assume caput i.e. chapter break

1,1 is the Bible reference as shown by the two popups

Superscript a-a – no tool tip translation but the BHS reveals a footnote marker to translate:

�� mouse over refers to Greek text of the Gottingen Septuagint. If it referred to a manuscript rather than a critical edition, this is where one would go to a Manuscript Explorer interactive to get details on the manuscript.

This is the only way I have found to work through an apparatus in a way to actual learn what data it provides and what all the sigla mean.

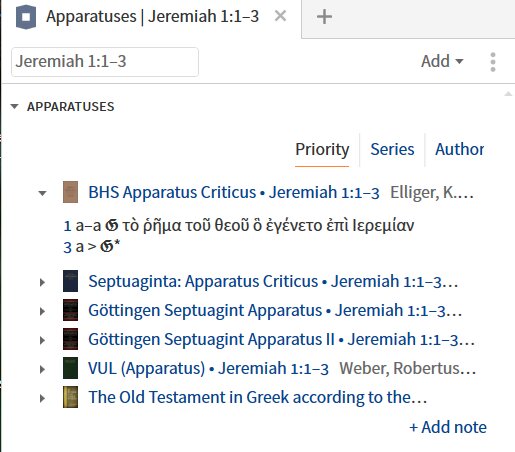

Apparatus in the Passage Guide

If one cares to extend one’s research beyond the BHS apparatus, open the Apparatuses Guide:

- Select Guides on toolbar

- Select Bible Reference Guides

- Select Apparatuses

Note there is one Hebrew, 1 Latin and 4 Greek apparatuses for this passage.

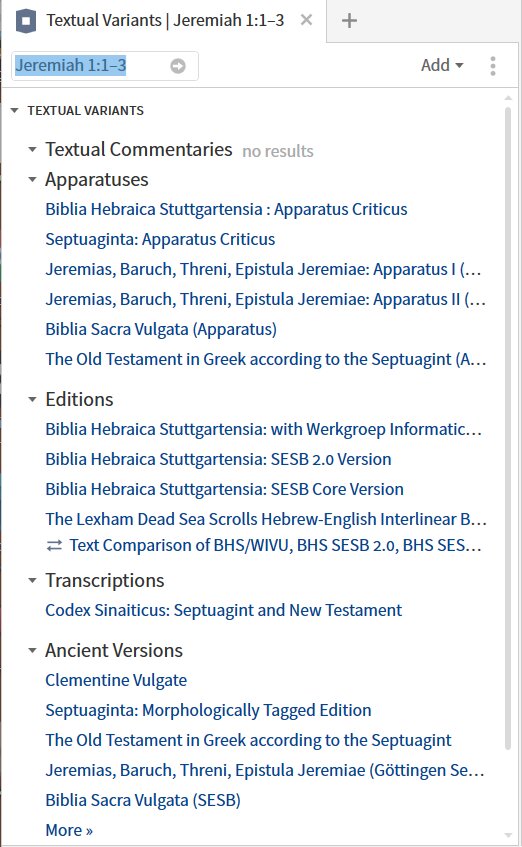

Textual Variants in the Passage Guide

The apparatus also appears in the bibliographic section Textual Variants. To open the Textual Variants Guide

- Select Guides on toolbar

- Select Bible Reference Guides

- Select Textual Variants

This section provides links to resources that include:

- Textual (Criticism) Commentaries

- Apparatuses

- (Critical) editions

- Transcriptions

- Ancient translation (critical) editions

In addition, there are interspersed options to initiate the Text Comparison tool with the resources shown preselected.

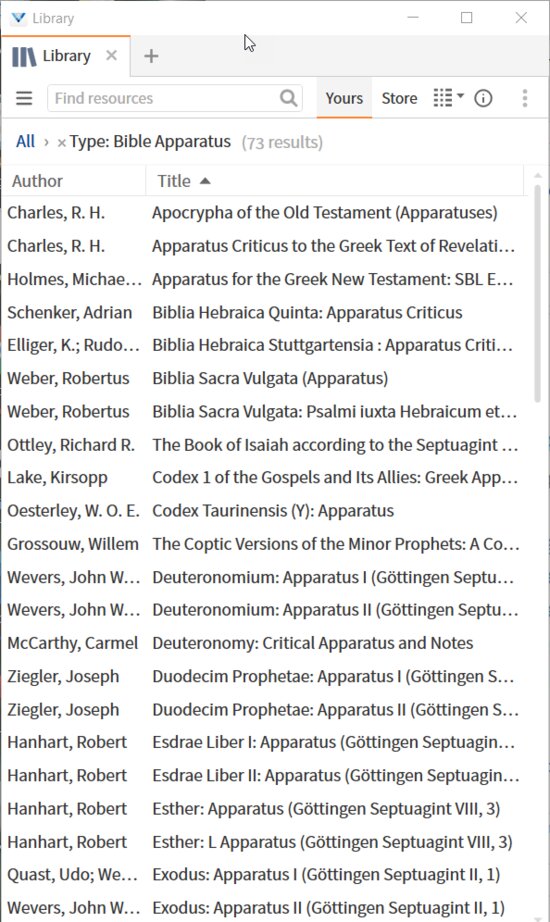

Library resource type

All Bible apparatuses are included under resource type:Bible Apparatus. You may also have apparatus for non-Biblical texts.

Reading lists: Catholic Bible Interpretation has been updated to include readings for text criticism. As always, I appreciate any additional recommendations.

Exercises beyond reading:

- Read a commentary highlighting the passages dependent upon textual criticsm

- Work through your top apparatuses for Hebrew OT, Greek OT, and Greek NT until you are comfortable that you understand how to use them

lxx Septuagint

[1] W. Randolph Tate, Handbook for Biblical Interpretation: An Essential Guide to Methods, Terms, and Concepts (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2012), 441–443.

[2] W. Randolph Tate, Handbook for Biblical Interpretation: An Essential Guide to Methods, Terms, and Concepts (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2012), 92–93.

* 1 The words of Jeremiah son of Hilkiah, of the priests who were in Anathoth in the land of Benjamin,

Jeremiah 1:1 (NRSV)

* 1 The words of Amos, who was among the shepherds of Tekoa, which he saw concerning Israel in the days of King Uzziah of Judah and in the days of King Jeroboam son of Joash of Israel, two years before the earthquake.

Amos 1:1 (NRSV)

* 2 to whom the word of the Lord came in the days of King Josiah son of Amon of Judah, in the thirteenth year of his reign.

Jeremiah 1:2 (NRSV)

* 1 The word of the Lord that came to Jeremiah concerning the drought:

Jeremiah 14:1 (NRSV)

* 1 The word of the Lord that came to the prophet Jeremiah concerning the nations.

Jeremiah 46:1 (NRSV)

* 1 The word of the Lord that came to the prophet Jeremiah concerning the Philistines, before Pharaoh attacked Gaza:

Jeremiah 47:1 (NRSV)

* 34 The word of the Lord that came to the prophet Jeremiah concerning Elam, at the beginning of the reign of King Zedekiah of Judah.

Jeremiah 49:34 (NRSV)

2 GKC, sec. 138e, note.

Jer The book of Jeremiah

[3] William Lee Holladay, Jeremiah 1: A Commentary on the Book of the Prophet Jeremiah, Chapters 1–25, ed. Paul D. Hanson, Hermeneia—a Critical and Historical Commentary on the Bible (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1986), 14.

[4] Patrick J. Hartin, James, ed. Daniel J. Harrington, vol. 14, Sacra Pagina Series (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2003), 50.

7 This breaks down with the absence of the fourth letter dālet and the missing letter lines of irregular meter between kap and peh (9:19–10:6).

[5] Konrad Schaefer, Psalms, ed. David W. Cotter, Jerome T. Walsh, and Chris Franke, Berit Olam Studies in Hebrew Narrative and Poetry (Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press, 2001), 26.

𝔊 versio lxx interpretum Graeca (secundum Septuaginta. Vetus Testamentum Graecum auctoritate Societatis Litterarum Gottingensis editum 1931 sqq, vel, ubi haec editio deest, secundum Septuaginta. Edidit A. Rahlfs 1935). Nullo signo adiecto, omnes vel gravissimi codices