Docx files for personal book: Verbum 9 part 1; Verbum 9 part 2; Verbum 9 part 3; Verbum 9 part 4; Verbum 9 part 5; Verbum 9 part 6; How to use the Verbum Lectionary and Missal; Verbum 8 tips 1-30; Verbum 8 tips 31-49

Reading lists: Catholic Bible Interpretation

Please be generous with your additional details, corrections, suggestions, and other feedback. This is being built in a .docx file for a PBB which will be shared periodically.

Previous post: Aside: Forum tidbits 1 Next post: Aside: Practice searches

Use of Stats Menu of Bible Book Explorer

From Mattillo:[1]

[quote]On a related note, could you explain the stats menu to me? I get the other options but I was trying to figure out how to use the Stats menu. There are options for Lemmas in pasage, used one in passage, roots, etc but I'm not quite sure what they are trying to show. Could the help/about option explain those better?

Response from Eli Evans (Faithlife):

[quote]I made this interactive. Howdy!

First off, you may not get value out of the Stats page, and that's okay.

That said, what it's trying to show is quantifiable relationships between the books in terms of their general (not specific) language usage. This is in the same spirit as the Charts tool, but instead of charting and comparing search results, it's charting and comparing counts of various phenomena that are difficult or impossible to construct a search for.

I chose an X/Y "scatter" plot instead of a regular bar or column chart because I didn't just want to show frequency or counts, I wanted to show how the books are related to one another. The most important relationship (in a statistical sense) is length. Any countable thing in a book is going to be in relation to its length, and the expected frequency of that thing occurring in that book is going be a function of its length.

For example, if you compare "Lemmas" to "Words", you are doing what is known as a type-token ratio (TTR), which is one way to measure the amount of lexical density in a text. Here's a pretty succinct explanation I found (here):

”In analysis of text, token refers to individual words, and type to the amount of unique words.

Type-token ratio is the division of those two, a crude measure of the lexical complexity in text. For example, if a 1000-word text has 250 unique words, it has a type/token ratio of 0.25, which is relatively low and suggests a simple writing style, or possibly legalese with a lot of repeated phrases.

Type-token ratios of different texts are not directly comparable as words in text usually follows a power law type of distribution, implying that longer texts will almost implicitly show a larger increase of tokens than of types.

One semi-brute way around this is to calculate type-token figures for same-sized chunks of the text, then average those for a single figure (which doesn't work too well if some documents are much shorter than the chunk size). [This is what the bar chart at the bottom of the Stats page underneath the scatter plot is showing, and why it's there. — Eli]

Type-token ratio is often one among various statistical figures/factors in text/corpus summaries. Consider plagiarism detection: if text was copied and reworded only slightly, it will have a comparable type-token ratio.

You may wish to apply stemming or lemmatization before calculating a type-token ratio, when you want to avoid counting simple inflected variations as separate tokens. [2]

A text with low lexical density uses the same words over and over, and one with high density shows more variation in its terminology. Lexical density is sometimes used as a crude measure of linguistic "sophistication" but that's not the full story. For example, proper names get counted, so a list of people with no repeats has a lexical density of 1:1, but the preamble to John's gospel—a much more sophisticated text that displays a remarkable economy of language—is much lower. (I like John. He uses small words to tell about big ideas.)

It should be unsurprising to find John uses a smaller inventory of lemmas than, say, Luke does. Or that poetry generally speaking is more dense than prose. We could just put the number of lemmas on a bar chart, but that would obscure the length factor, how say, 2 Jn is much shorter than Luke. Putting it on the scatter plot lets you see which books are:

- longer and have more lemmas (higher relative lexical density)

- longer and have fewer lemmas (lower relative lexical density)

- shorter and have more lemmas (higher relative lexical density)

- shorter and and have fewer lemmas (lower relative lexical density)

If you choose "Roots" you are examining the same type-token relationship, just with a more primitive "type", the root.

You can see this kind of analysis being done on the pastoral epistles in Carson & Porter's Linguistics and the New Testament: Critical Junctures, and in other books. Search for "type token" in your library and you may find some real-world applications.

If you choose chapters or verses from the second drop down (I almost never would, to be honest) you are simply choosing a different measure for the length of a book.

So choosing "Lemma" or "Roots" is a measure of how diverse the book's vocabulary is in relation to its length.

The other options in the drop down have to do with how unique the book's vocabulary is. Hapax legomena are words that occur only once within a given corpus, eg, ἀγαθοποιός, agathopoios occurs in 1 Pet 2:14 and nowhere else in the NT. Because the meaning of a word is established by how it's used, and these words are used infrequently, they attract a lot of examination and generate a lot of debate.

If lexical density is a rough and ready way to compare overall complexity of a text, hapax are a rough approximation of its obscurity. Job has a lot of hapax, and that (among other things) makes it relatively weird. Note that some (many) hapax are just proper names, unique but not particularly obscure.

Anyway, we went one step further than the typical hapax definition of words that are used only once in the corpus. What about lemmas/roots that are used only once in the book? (We wanted to do lemmas/roots per author, eg, this word used once in Paul, but that got dicey outside of the NT letters. Might revisit.)

How about lemmas/roots that are used in this book, perhaps many times, but in no other book in the corpus? That's a measure of the uniqueness of the book's vocabulary relative to others. Again, versus the length.

One thing that I wanted to do was to include word lists of the unique lemmas/roots per book, but time was not my ally. You can get to those lists for a book by using the Concordance tool. Make a concordance of, say, SBL Greek New Testament, and then choose Lemma and narrow it down to a single book.

Use of Eusebian canons

From Therese:[3]

[quote]How can I find Luke sayings that are in either Matthew or Mark?

From HJ. Vsn der Wal

[quote]In the desktop software I would use the Parallel Gospel Reader tool, but you could also just open the Eusebian Canons (provided that you have this resource in your library). The Eusebian Canons are an ancient gospel harmony. Canon V contains all passages that occur in Matthew and Luke (but not in the other two gospels) and canon VIII will give you all passages that occur in Luke and Mark (but not in Matthew and John).

See Factbook: Eusebian Canons

Understanding Talmud references

From Mark Barnes:[4]

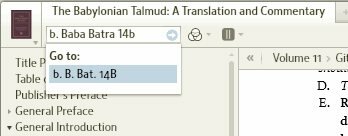

[quote]There are two main ways of referencing the Talmud. Goldingay's method can be broken down like this:

b. Baba Batra 14b

- b. = Babylonian Talmud

- Baba Bata = The "Baba Bata" tractate.

- 14 = The 14th folio

- b = The 'b' side of the folio

The problem with this method is that it's not precise. A folio is basically a page, so it's a large unit, and unit breaks don't occur in syntactically logical places. So Neusner uses a much more precise referencing system that breaks up the talmud into much smaller units.

Thankfully the Logos edition uses both systems. If you had opened the Talmud, and typed "b. Baba Batra 14b" into the reference box, you would have the suggestion of "b. B. Bata 14B". You could click on the suggestion and go straight to the location (see screenshot). You'll see a [14b] in the middle of the text, and many lines further down you'll see a [15a] which indicates the start of the next folio (if you miss it, it's a few lines just after "Who Wrote Various Books of Scripture?"). From Goldingay's reference you'll know the quote must be after [14b] and before [15a], but you can't place it any more precisely.

Neusner's reference point for the quote you're interested in is b. B. Bat. 1:6, IV.8.C. This would not normally be given to this precision in other works, but it wouldn't be unusual to see a reference to b. B. Bat. 1:6.

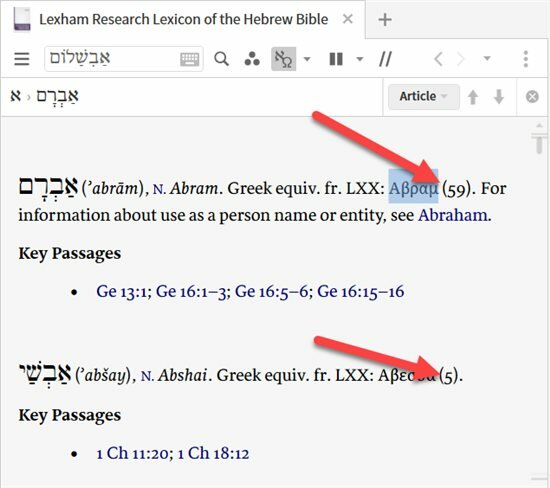

What is the meaning of this data in The Lexham Lexicon of the Hebrew Bible?

From MJ Smith:[5]

[quote]What do these numbers (at end of red arrow) mean?

Response from Rick Brannan (Faithlife):

[quote]Number of times the Hebrew lemma is translated by the specified Greek lemma

Advanced “Root” Search example

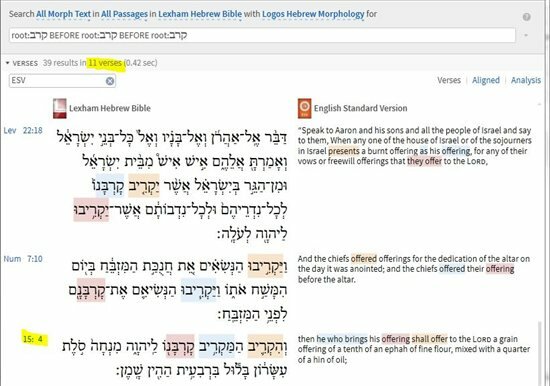

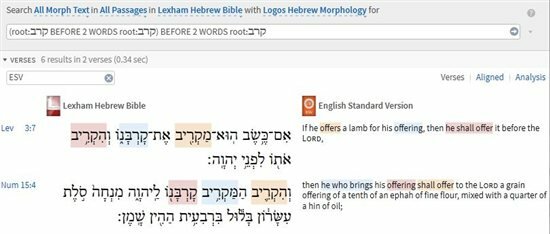

From Fr. Devin Roza:

[quote]Today I was reading Numbers 15:4 in Hebrew, and I noticed that the verse opens with three consecutive words, all of which share the same root in Hebrew: קרב. The verse opens like this: וְהִקְרִ֛יב הַמַּקְרִ֥יב קָרְבָּנ֖וֹ. The RSVCE translates it "then he who brings his offering shall offer". In Hebrew, however, the three repeated roots sound more like what in English would sound "The offerer shall offer his offering".

The root is repeated three times in a row, the first two times from the verb lemma, and the third time from a completely different lemma, a noun ("offering").

So, I found this curious and thought I would investigate whether or not there are other verses in the Hebrew Bible which have this root in three consecutive words. This is the search I found that seemed to work best:

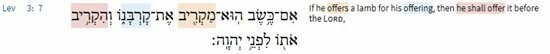

So, 11 verses have this root at least three times. Numbers 15:4 is included in the results. Scrolling through the results, there seems to only be one other verse where the root appears three consecutive times, Lev 3:7:

This was confirmed by this subsequent search like this:

If I rerun the search changing "BEFORE 2 WORDS" to "BEFORE 1 WORDS", then only Num 15:4 results, as the search engine considers the את connector to be a word.

Interestingly, the three words used in both Num 15:4 and Lev 3:7 are the same - same verb form, same participle form, same noun form, although the translation of the phrase is quite different.

I thought it might be interesting to do a search in general for any root that appears three consecutive times, but I'm not sure how, or if it is possible. If anyone has any idea please share.

Either way, hope this gets you thinking of how to use this new "root" functionality to study God's Word. It opens up some very interesting new possibilities.

Materials for Sunday of the Word of God (Catholic)

Slide markup codes

From Christ Gadiage:

[quote]I'll add more as I stumble over them, but it sure would be nice to have an official list from the programmers.

Here's what I've discovered so far:

-- (Double dash) - start new slide

*text* - italicize text

**text** - bold text

***text*** - bold & italicize text (doesn't always work)

__text__ (double underline) - underline text

*__text__* - italicize & underline

**__text__** - bold & underline

***__text__*** - bold, italicize & underline

Why doesn’t the title and the citation data match?

From MJ Smith:

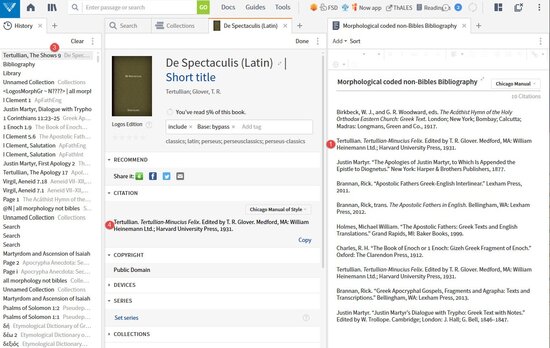

[quote]Is this resource De Spectaculus or Minucius Felix?

Response from Kyle G. Anderson (Faithlife):[7]

[quote]At this time we're not able to support searching within your library for bibliographic citation data (i.e. screenshot #4).

This particular resource/project is an interesting one. It comes from the Perseus project which was a special project on our part that pulled files from a website to produce both resource and metadata. Because of the way Perseus kept their files they split up print books (i.e. the citation data) into individual resources (e.g. De Spectaculis). Because of the special nature of this project it is unlikely that we will be able to go back and tweak the metadata for all the titles in the project.

[1] Bible Book Explorer Manual? - Faithlife Forums (logos.com) accessed 5/29/2021 10:46 PM

[2] Type-token ratio - Helpful (knobs-dials.com) date of original access unknown

[3] Comparing Luke with Mathew and Mark - Faithlife Forums (logos.com) accessed 5/29/2021 11:03 PM

[4] Help with referencing the Talmud please... - Faithlife Forums (logos.com) accessed 5/29/2021 11:22 PM

[5] What is the meaning of this data in The Lexham Lexicon of the Hebrew Bible. - Faithlife Forums (logos.com) accessed 5/29/2021

Slide markup codes - Faithlife Forums (logos.com) accessed 5/30/2021 12:00 AM

Slide markup codes - Faithlife Forums (logos.com) accessed 5/30/2021 12:00 AM

[7] RESOLVED KYLE: BUG: And the actual name of the resource is? - Faithlife Forums (logos.com) accessed 5/30/2021 12:30 AM