Docx files for personal book: Verbum 9 part 1; Verbum 9 part 2; Verbum 9 part 3; Verbum 9 part 4; Verbum 9 part 5; Verbum 9 part 6; How to use the Verbum Lectionary and Missal; Verbum 8 tips 1-30; Verbum 8 tips 31-49

Reading lists: Catholic Bible Interpretation

Please be generous with your additional details, corrections, suggestions, and other feedback. This is being built in a .docx file for a PBB which will be shared periodically.

Previous post: Aside: Personal searches 2 Next post: Aside: Person roles

Aside: Catholic Bible Interpretation - Source Criticism

Questions Typically Asked

From Felix Just, S.J.:

[quote]

Does the text have any underlying source or sources?

Which version of a source was used, in case there is more than one?

What do the sources actually say and mean in their original contexts?

How are the sources used (quoted, paraphrased, adapted?) in the later text?

The best known examples of this method is the division of the Torah into four sources (J jahwist, E Elohist, D Deuteronomic, and P priestly) and the positing of a document Q as a forerunner of the Gospels. In early Logos, the Andersen-Forbes coding provided source information for the Pentateuch and Jeremiah. When Andersen-Forbes was replaced as the reverse interlinear, there was a significant gap before the release of the Source Criticism dataset[1] for the Pentateuch only. There is nothing for Jeremiah or the Gospels.

W. Randolph Tate treats source criticism as one of the three major elements of the historical-critical method, the other two being form criticism and redaction criticism.[quote]

SOURCE CRITICISM

One component in the historical-critical method, source criticism is the study of biblical texts in terms of the sources used in their composition. The goal is not simply to isolate and study the sources as documents in their own right but also to examine the manner in which biblical authors adapt earlier documents to their own unique purposes.

Source criticism has enjoyed a long and venerable career in both hebrew bible and nt studies. Source-critical studies of the Hebrew Bible have focused on the pentateuch but more recently have included other parts of the Hebrew Bible. For centuries, the Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch was generally accepted without much question. Gradually, however, scholars began to doubt whether everything in the Pentateuch could be from the hand of Moses. Under the influence of seventeenth-century rationalism and because of passages that could not have been from Moses (e.g., the account of Moses’s death [Deut. 34:5–8], familiarity with the monarchy [Gen. 36:31–39], and the phrase “until this day,” which suggests that the passages containing it were written after the time of Moses [Gen. 35:4 Lxx; Deut. 34:5–6]), many scholars further questioned Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch. Based on these passages and other discoveries—such as historical inaccuracies, repetitions, and divergent writing styles—these scholars concluded that the Pentateuch was the product of an extended process of compilation.

Pentateuchal studies. In the second half of the nineteenth century, Julius Wellhausen and Abraham Kuenen popularized the view that the Pentateuch and, more broadly, the hexateuch are made up of four sources. Both Wellhausen and Kuenen detected a close relationship between the Pentateuch and the book of Joshua. They therefore spoke of the four-source hypothesis as relating to the Hexateuch. Later followers of Wellhausen claimed that the sources of the Hexateuch also formed the basis of the books through Kings. All subsequent source-critical scholarship is deeply indebted to Wellhausen, and many scholars today feel that the four-source theory is still the best explanation for the composition of the Pentateuch. For a concise and informative discussion of the challenges and alternatives to Wellhausen, see van der Woude, 166–205.

Scholars did not begin with the assumption that these texts necessarily adopted and adapted earlier traditions and documents; rather, in reading the texts closely, they discovered what they assumed to be evidence of different sources within the texts, particularly within the Pentateuch. These different sources were evidenced by parallel accounts of the same event, combined accounts of the event, different literary terminology, different literary structures within an account or between accounts, different theological viewpoints, and a variety of recurring motifs. Habel suggests that the examination of texts through the grid of source criticism should focus on three categories of issues: literary style, terminology, and perspective, or point of view. Under each of these categories, Habel has identified subcategories. Under issues of literary style are writing techniques, structural arrangement, and use of language. Under the issues of terminology are recurring terms, names, key expressions, and clusters of words. And under the issue of perspective are central thrust and vantage point.

In source criticism of the ot, the documentary hypothesis (or four-source hypothesis) is straightforward. The four sources (see d; e; j; p) or documents were composed at different times and for different purposes. Each source thus constitutes a layer within the Hexateuch, and each layer has its peculiar language, style, and theological viewpoint (van der Woude, 188–90). For a detailed description of these four sources, see graf-wellhausen hypothesis.

New Testament studies. Although source criticism has been applied to all the writings of the nt, its primary focus there has been on the synoptic gospels. This focus is twofold: a concern for the relationship between two or more texts that suggests some kind of dependence, and the discovery of sources within a single text.

The nineteenth century witnessed a tremendous concern to uncover the history behind the Gospels. A great deal of energy was expended especially in the attempt to reconstruct the life of Jesus. For this reason, the Gospels were treated as sources for reconstructing history. If one Gospel was earlier than the others, then that one should be historically more reliable, for it would have been closer to the actual events. In the first quarter of the twentieth century, B. H. Streeter proposed a solution to the relationship between the Synoptic Gospels that became popular in the English-speaking world (see four document hypothesis). His explanation was a refinement of H. J. Holtzmann’s (1832–1910) two-source hypothesis. This solution remains dominant in source-critical studies today. Simply put, this hypothesis claims that Mark was the first Gospel and was a source for both Matthew and Luke. It also claims that Matthew and Luke made use of another, no longer extant source, which has come to be known as q (probably from German Quelle, “source”).

Recent scholarship has challenged the assumption that the Gospels can serve as sources for reconstructing the life of Jesus. Scholars today generally recognize not only that the Gospels are separated from the events they describe by at least a generation (Mark was composed ca. 70 ce, and Matthew and Luke between 80 and 90 ce) but also that the Gospels are theologically rather than historically motivated. Also, the two-source hypothesis has met with significant criticism. One older hypothesis (the griesbach hypothesis) claims that Matthew and Luke were written before Mark, and Mark borrowed from them, especially where Matthew and Luke agree.

Source criticism is also concerned with identifying lost sources within the text. When they encounter a portion of a text thought to be uncharacteristic of the author’s style, vocabulary, or ideology, source critics usually suspect that the author has drawn from a source. An example of this is John 21, where the vocabulary differs significantly from that found in the rest of the Gospel (ischyein rather than dynasthai, and exetazein instead of erōtan). In Rom. 3:25–26 (tev), we encounter the idea that God has “overlooked” past sins (nrsv: “divine forbearance”). This seems to contradict (not only in vocabulary but also in concept) what Paul has already claimed in Rom. 1–2, that God punishes all sin (Tuckett, 85). Some suspect Paul’s use of a source here.

Source critics assume that an author’s usual or normal vocabulary, style, and ideology can be discovered. But can scholars sufficiently define an author’s normal vocabulary, style, and ideology and then use that definition as a canon by which to determine whether a passage is or is not the work of that author? Most source critics think so.

Bibliography. Norman Habel, Literary Criticism of the Old Testament (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1971); Christopher Tuckett, Reading the New Testament: Methods of Interpretation (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1987); Moshe Weinfeld, Deuteronomy and the Deuteronomic School (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1972); A. S. van der Woude, ed., The World of the Old Testament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1989).[2]

Like text criticism, source criticism requires fluency in the original languages so most of us are left with evaluating and verifying the work of others. The primary scriptures which are subjected to source criticism are:

- The Pentateuch (J,E, D, P)

- Books of history with explicit references to:

- Acts of Solomon (1 Kings 11:41)

- Chronicles of the Kings of Judah (1 Kings 14:29)

- Chronicles of the Kings of Israel (1 Kings 14:19)

- Book of Jashar (Joshua 10:12-14)

- Book of the Wars of the Lord (Numbers 21:14)

- Isaiah (proto, deuteron, trito)

- Ezra-Nehemiah (communications with officials, lists, Ezra memoirs, Nehemiah memoirs)

- Jeremiah (Mowinkel)

- Synoptic Gospels (Q)

- Gospel of John (Signs Gospel)

Elements examined in Source criticism as listed by David Wenham[3] include:

- When there are overlapping texts e.g., synoptic gospels

- Wording

- Order

- Contents – omissions, doublets, misunderstandings

- Style

- Ideas and theology

- External evidence

- When there are no overlapping texts

- Breaks and dislocations of the sequence

- Stylistic inconsistency

- Theological inconsistency

- Historical inconsistencies

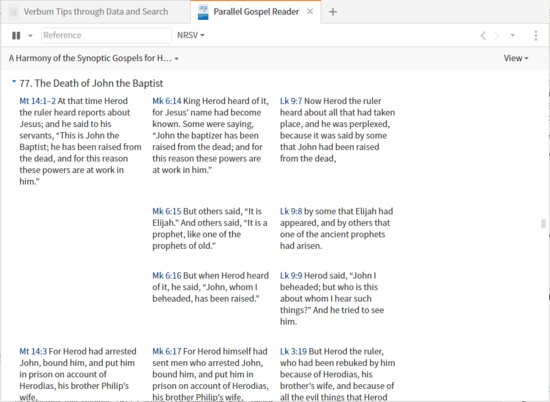

Parallel Gospel Reader; Synopsis of Samuel, Kings, and Chronicles

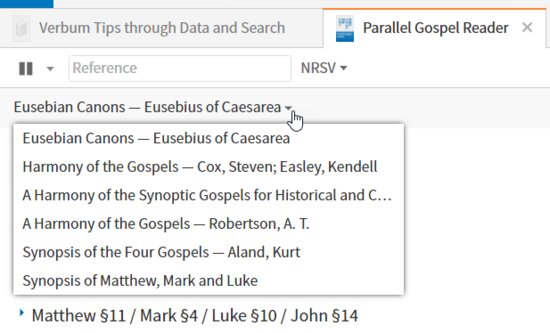

For overlapping texts, Verbum offers the Parallel Gospel Reader: Toolsà Interactive Media à Parallel Gospel Reader. This tool essentially offers the library resources of type:Harmonies for the Gospel in a format that allows the user to select the translation and the Gospels shown.

The available resources for this reader include:

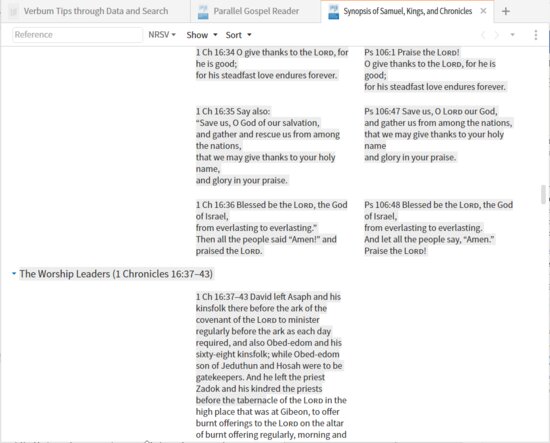

The second parallel reader is of more use in identifying fragmentary shared sources, as in this case of a psalm:

Note that there is no similar readers for the New Testament epistle parallels.

Style and vocabulary

Verbum offers little explicit support for text analysis. MAXQDA offers a free 187 page book[4] (PDF) that provides examples of a variety of text analysis – none directly Biblical but very useful for generating ideas of Biblical applications.

Tools that can be utilized for statistical analysis of grammar, vocabulary, and some stylistic elements:

- Highlighting

- Visual filter

- Search in analysis mode

- Concordance tool (not to be confused with Concordance guide)

- Passage analysis tool: morph river

- Passage analysis tool: word tree

Note that academically the focus is shifting from source criticism towards redaction criticism as the primary area of exploration.

Readings on source criticism are available in Reading lists:

Catholic Bible Interpretation

[1] Parks, Jimmy. Source Criticism in the Bible Dataset Documentation. Bellingham, WA: Faithlife, 2018.

d Deuteronomistic source

e Elohist source

j Jahwist (Yahwist) source

p Priestly source

q Gospel sayings source (perhaps from the German Quelle, “source”)

ca. circa

tev Today’s English Version = Good News Bible

nrsv New Revised Standard Version

[2] W. Randolph Tate, Handbook for Biblical Interpretation: An Essential Guide to Methods, Terms, and Concepts (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2012), 417–419.

[3] David Wenham, “Source Criticism,” I. Howard Marshall, ed., New Testament Interpretation: Essays on Principles and Methods, 1977. Carlisle: The Paternoster Press, revised 1979. Pbk. ISBN: 0853644241. pp.139-152. Accessed via Microsoft Word - nti_8_source-criticism_wenham.doc (biblicalstudies.org.uk) at 6/5/2021 4:10 PM

[4] Michael C. Gizzi, Stefan Rädiker. The Practice of Qualitative Data Analysis: Research Examples Using MAXQDA ISBN: 978-3-948768058