Docx files for personal book: Verbum 9 part 1; Verbum 9 part 2; Verbum 9 part 3; Verbum 9 part 4; Verbum 9 part 5; Verbum 9 part 6; Verbum 9 part 7; How to use the Verbum Lectionary and Missal; Verbum 8 tips 1-30; Verbum 8 tips 31-49

Reading lists: Catholic Bible Interpretation

Please be generous with your additional details, corrections, suggestions, and other feedback. This is being built in a .docx file for a PBB which will be shared periodically.

Previous post: Tip 9aj Next post: Tip 9al

Textual Variants

The Textual Variants guide contains six independent sections, each with their own resources, data, and use. Their common element is that they represent textual criticism.

[quote]TEXTUAL CRITICISM

A criticism whose primary task is to compare the many biblical manuscripts and manuscript families in order to produce a Greek or hebrew version that most closely approximates the original. Its aim is threefold: (1) to determine the transmission process of a text and the reason it exists in variant forms; (2) to determine the original wording if possible; and (3) to produce a reliable Greek or Hebrew text.

None of the autographs of the biblical texts survive, only copies of copies, the earliest for the hebrew bible dating from the seventh century bce (if one includes some short fragments of text) and, for the nt, from the second century ce. Since the available copies were handwritten by scribes and because there exists a gap between the originals and the earliest copies, textual critics cannot assume with complete certainty that they have recovered the original wording of the biblical texts.

Since the thousands of manuscripts (from complete texts to fragments) exist in various translations (Greek, Latin, Syriac, Coptic) and in quotations in other kinds of texts, there are four broad categories of variants: (1) between manuscripts in the original languages; (2) between manuscripts in early translations; (3) between ancient manuscripts in the original languages and early translations; and (4) between quotations in early Jewish and Christian writings. But variants may also be intentional or unintentional. Intentional variants appear when scribes changed the wording of the text. The wording could be changed in order to correct a perceived spelling or grammatical error. Scribes also made changes in syntax, rearranging the word order and sentence and paragraph structure. Additions, omissions, changes, transpositions, and glosses were made in order to improve the text. Scribes also introduced theological and doctrinal changes to make the text conform to a more orthodox position. Substitutions were sometimes made to remove what might seem to a scribe to be offensive material. Regardless of the type of intentional changes made, textual critics usually assume that the intention of the scribes was to improve the text.

Unintentional variants are usually those resulting from sight or hearing. Copying errors occurred when the scribe would look at the manuscript and then attempt to copy from it. For example, the scribe might skip a word or line, write a word or line twice, misspell a word, reverse the order of letters within a word, or confuse the order of words within a sentence. When a number of scribes were making copies while listening to a reader of a manuscript, errors of hearing were possible. A scribe might not hear the word or group of sentences correctly or might not write correctly what he did hear. Sometimes scribes would make notes or glosses in the margins of texts, and then years later these might be taken as part of the texts and incorporated into new manuscripts by copyists. However, many ot textual critics doubt the “errors of hearing” problem.

With all the possible variants, how do textual critics determine the most plausible version? Generally, critics rely on two types of evidence: internal and external. As the term suggests, internal evidence arises from within the text itself. Since textual critics are familiar with the process by which ancient texts were composed, copied, preserved, and transmitted, they have identified the types of variants and the reasons they occur. Consequently, in trying to establish the most plausible version, textual critics simply work backward from the variants toward the original. First, on the assumption that scribes tended to correct or smooth out difficulties, textual critics claim that when one is choosing between variants, the more difficult reading is to be preferred. Second, because scribes tended to expand texts rather than delete elements from them, the shorter reading is probably closer to the original. Third, since copyists tended to harmonize different versions of the same text, versions that seem to be harmonistic are rejected in favor of a more dissonant one. Fourth, when variant readings seem not to conform to an author’s style, tone, or vocabulary within the same document or in other texts, textual critics generally reject these as inauthentic.

External evidence includes considerations outside the text, such as the date and nature of the manuscripts, the geographical locations of the manuscripts, and the relationship between families of texts. As the biblical writings began to spread throughout the Mediterranean world, certain cities became what critics call “homes” of versions of texts and textual traditions. In other words, in places such as Rome, Alexandria, and Constantinople, certain definable textual traditions arose. Textual critics have assigned the various nt and lxx versions to families or recensions based on their similarities and identification with geographical areas. Furthermore, textual critics have discovered that some families of texts tend to expand the material when compared with other groups. So if the critic is weighing the external evidence between a version where one group of manuscript witnesses reveals an expansionist tendency while another one does not, the textual critic will generally choose the latter reading. A second external piece of evidence is the date of the manuscript witnesses. Generally, the critic will assume that the earlier version is more likely to be authentic. A third point of external evidence is that manuscript witnesses are weighed rather than counted. For example, it is possible for one reading to be found in a number of fifth-century witnesses but another reading in a single tenth-century witness that better satisfies the components of internal evidence. Therefore, the textual critic would choose the single tenth-century witness as the more authentic one.

Critical editions of the nt and the Hebrew Bible are in the original languages and contain a critical apparatus, an extensive set of footnotes that list variants and the ancient sources (manuscripts, translations, versions, commentaries, quotations) in which the variants occur. Some critical editions include only some of the variants; others list every variant within a text. Although modern translations do not have a critical apparatus, those that are committee translations are based on serious attention to the apparatus of the critical editions. They sometimes offer footnotes that indicate the most crucial variants and include abbreviated information on the type of variant (addition, omission, etc.).

Once the critic has accumulated both internal and external evidence, the critic makes a decision as to which reading best approximates the original. Since no originals are extant, textual criticism depends on the available evidence and the informed judgment of the critic. For an excellent introduction to textual criticism, see Voelz.

Bibliography. J. Harold Greenlee, Introduction to New Testament Textual Criticism (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1964; rev. ed., Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1995); John H. Hayes and Carl R. Holladay, Biblical Exegesis: A Beginner’s Handbook (Atlanta: John Knox, 1987); Ralph W. Klein, Textual Criticism of the Old Testament (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1974); Charles B. Puskas, An Introduction to the New Testament (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1989); Emanuel Tov, Textual Criticism of the Hebrew Bible (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1992); James W. Voelz, What Does This Mean? Principles of Biblical Interpretation in the Post-modern World (St. Louis: Concordia, 1995).[1]

From Verbum Help:[quote]

Textual Variants Section

The Textual Variants section is available in the Exegetical Guide, and it gathers text-critical information on a verse or passage from all related resources in the Library and lists them by category. This section allows users to survey in-depth text-critical resources and helps them to find the information they need.

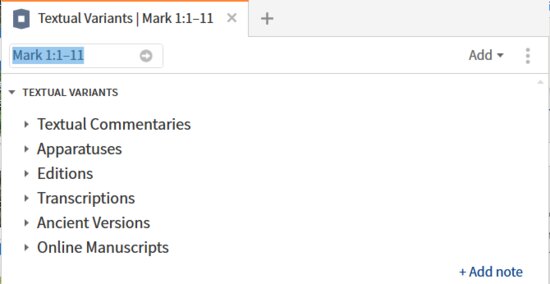

This section includes several collapsible sub-sections.

• Textual Commentaries

• Apparatuses

• Editions

• Ancient Versions

• Online Manuscripts

The online manuscripts section is only available for New Testament references.[2]

Section heading bar

The section heading bar and menu are the minimal defaults – no settings, no saving. However, the contents is divided into six independent sections. Each section will be discussed independently to keep the discussion clear and focused.

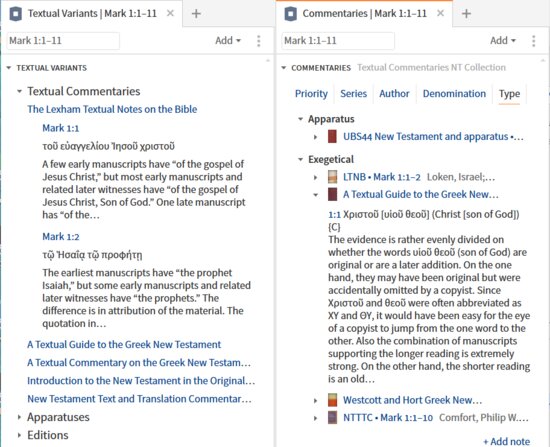

Textual Commentaries

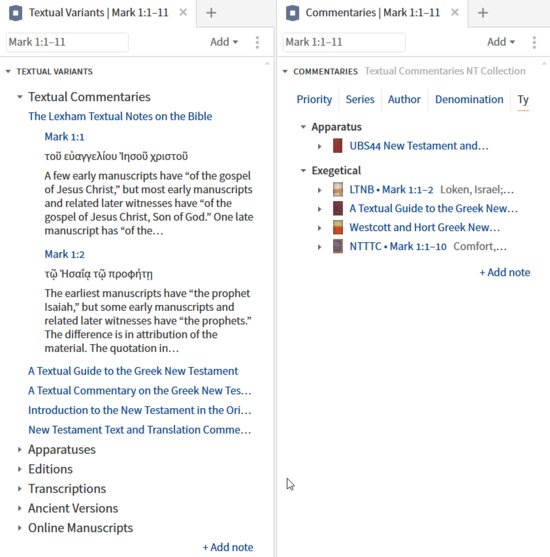

If you look back at the Commentaries guide section, you will find there is no “Textual Commentaries” category. In this particular case, it includes apparatus and exegetical commentaries.

Yes, the resources in the Commentary section correspond to those in the Textual commentaries subsection – the apparent differences are the result of series name vs. resource name identification. This is an inconsistency that Faithlife should address.

It is important to remember that commentaries such as France, R. T. The Gospel of Mark: A Commentary on the Greek Text. New International Greek Testament Commentary. Grand Rapids, MI; Carlisle: W.B. Eerdmans; Paternoster Press, 2002 which have a dedicated Textual Notes section are not included. You may wish to create a collection of such commentaries to use in a separate search.

Prerequisite reading: none

Resources included: not documented but include at least:

- Westcott, B. F., and F. J. A. Hort. Introduction to the New Testament in the Original Greek: Appendix. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1882.

- Brannan, Rick, and Israel Loken. The Lexham Textual Notes on the Bible. Lexham Bible Reference Series. Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2014.

- Comfort, Philip W. New Testament Text and Translation Commentary: Commentary on the Variant Readings of the Ancient New Testament Manuscripts and How They Relate to the Major English Translations. Carol Stream, IL: Tyndale House Publishers, Inc., 2008.

- Metzger, Bruce Manning, United Bible Societies. A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament, Second Edition a Companion Volume to the United Bible Societies’ Greek New Testament (4th Rev. Ed.). London; New York: United Bible Societies, 1994.

- Omanson, Roger L., and Bruce Manning Metzger. A Textual Guide to the Greek New Testament: An Adaptation of Bruce M. Metzger’s Textual Commentary for the Needs of Translators. Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 2006.

In my library, I find no evidence of other resources even for the Old Testament or Deuterocanon.

Contents

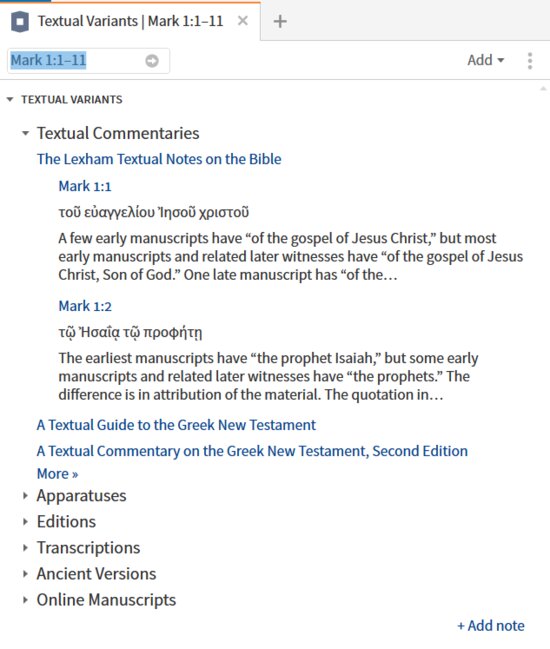

The data is multilayered for The Lexham Textual Notes on the Bible only. All other resources only show the resource title.

- Textual commentary resource title

- Up to 3 occurrences of the detail date before a “more” is used

- Bible reference

- Original language text being commented one

- Textual comment

- “more” is used after three titles

Interactions on data

|

Visual cue

|

Data element

|

Action

|

Response

|

|

Blue text

|

More

|

Click

|

Adds another block of data to the content of the guide.

|

|

Resource title;

Bible reference

|

Mouse over

|

Opens a popup preview of the resource text starting at the applicable text.

|

|

Click

|

Opens the resource to the start of the applicable text.

|

|

Right click

|

Opens the Context Menu.

|

|

Drag and drop

|

Opens the resource to the start of the applicable text at the location selected by the user.

|

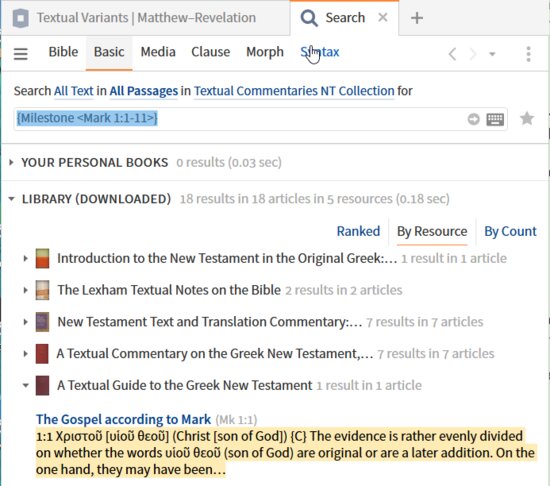

Search

If one can develop a collection of “textual commentaries”, then a search in the form of {Milestone <Mark 1:1-11>} will select the relevant passages. The problem is determining what commentaries belong in the collection.

Supplemental materials

The Textual Commentaries section can be duplicated by the Commentaries section by limiting in the input to the textual commentaries subset. But as noted above, identifying the appropriate commentaries is not a simple task.

lxx Septuagint

[1] W. Randolph Tate, Handbook for Biblical Interpretation: An Essential Guide to Methods, Terms, and Concepts (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2012), 441–443.

[2] Verbum Help (Bellingham, WA: Faithlife, 2018).