Docx files for personal book: Verbum 9 part 1; Verbum 9 part 2; Verbum 9 part 3; Verbum 9 part 4; Verbum 9 part 5; Verbum 9 part 6; Verbum 9 part 7; How to use the Verbum Lectionary and Missal; Verbum 8 tips 1-30; Verbum 8 tips 31-49

Reading lists: Catholic Bible Interpretation

Please be generous with your additional details, corrections, suggestions, and other feedback. This is being built in a .docx file for a PBB which will be shared periodically.

Previous post: Tip 9al Next post: Tip 9an

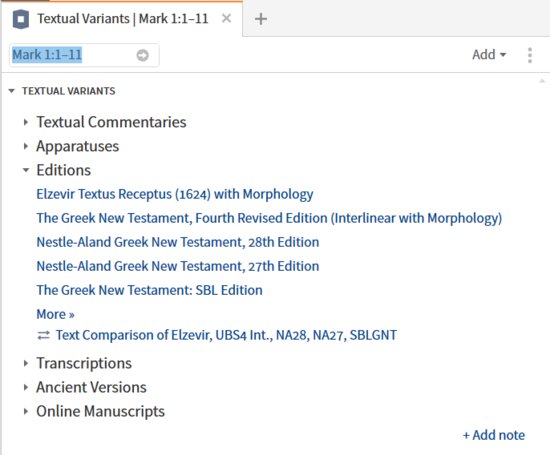

Editions

Can you describe the differences between these kinds of texts?

- Collations

- Critical

- Diplomatic

- Eclectic

- Facsimile

- Hypertext

- Parallel-text

If not, please read:

Yes, you need all three articles for definitions of all the types of texts listed above. Notice that all three deal with ancient texts where autographs i.e. original manuscripts are unavailable.

The Textual variants guide section trims the list down to four types:

- Editions

- Transcriptions

- Ancient versions

- Online manuscripts

Prerequisite reading: Widder, Wendy. Textual Criticism. Edited by Douglas Mangum. Lexham Methods Series. Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2013. This contains short descriptions of many of the critical editions.

Resources included (from my library);

- 1881 Westcott-Hort Greek New Testament

- Biblia Hebraica Quinta

- Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia: SESB 2.0 Version

- Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia: SESB Core Version

- Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia: with Werkgroep Informatica, Vrije Universiteit Morphology

- Byzantine/Majority Textform Greek New Testament

- Cambridge Greek Testament: Greek Text

- Elzevir Textus Receptus (1624) with Morphology

- Greek Text from A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Gospel according to St. John, Volumes 1 & 2

- Greek Text from A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Revelation of St. John

- Nestle-Aland Greek New Testament, 27th Edition

- Nestle-Aland Greek New Testament, 28th Edition

- Nestle-Aland Greek New Testament, 28th Edition: GBS

- Novum Testamentum Graece

- Novum Testamentum Graece (Tischendorf)

- Novum Testamentum Graece, Varia Lectio (Tischendorf)

- Sahidica: New Testament according to the Egyptian Greek Text

- Scrivener’s Textus Receptus (1881)

- Scrivener’s Textus Receptus (1894) with Morphology

- St. Paul’s Epistle to the Ephesians: Greek Text

- St. Paul’s Epistle to the Ephesians: Text

- St. Paul’s Epistle to the Galatians: Text

- St. Paul’s Epistles to the Philippians, Colossians, and to Philemon: Text

- St. Paul’s Epistles to the Thessalonians: Text

- St. Paul’s First Epistle to the Corinthians: Text

- Stephen’s Textus Receptus (1550) with Morphology

- The Book of Genesis in Hebrew, with Various Readings, Notes, Etc.

- The Book of Ruth in Hebrew, with A Critically-Revised Text

- The Expositor’s Greek Testament, Volume I (Matthew–John): Greek Text

- The Expositor’s Greek Testament, Volume II (Acts–1 Corinthians): Greek Text

- The Expositor’s Greek Testament, Volume III (2 Corinthians–Colossians): Greek Text

- The Expositor’s Greek Testament, Volume IV (1 Thessalonians–James): Greek Text

- The Expositor’s Greek Testament, Volume V (1 Peter–Revelation): Greek Text

- The Gospel according to St Mark: Greek Text (1914) CGTSC

- The Greek New Testament, Fifth Revised Edition (with Morphology)

- The Greek New Testament, Fourth Revised Edition (Interlinear with Morphology)

- The Greek New Testament: SBL Edition

- The Greek Testament (Text and Notes)

- The Interlinear Literal Translation of the Greek New Testament

- The Lexham Dead Sea Scrolls Hebrew-English Interlinear Bible

- The Lexham Greek-English Interlinear New Testament

- The Lexham Greek-English Interlinear New Testament: SBL Edition

- The NET Bible: Greek Text

- The New Testament in Greek (Scrivener 1881)

This list is a subset of type:Bible lang:Greek,Hebrew,Aramaic. Because the Septuagint is treated as an Ancient Version, this omits the portions of the Old Testament originally written (or known only) in Greek. There is no documentation on the criteria for being in the subset.

Contents

The contents of the Textual variants – editions subsection is simple:

- List of resources matching the passage criteria

- More to display additional entries

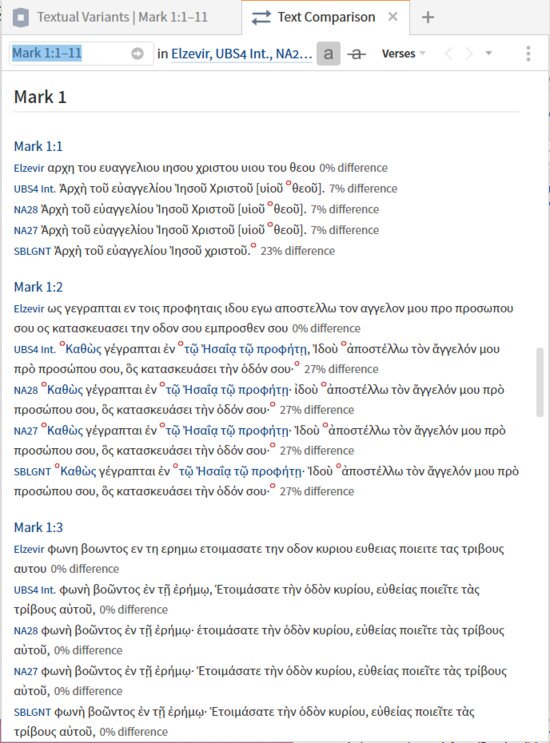

- A link for a prebuilt text comparison for the major editions

Note there is no documentation on how the editions specified in the text comparison are selected.

Interactions on data

|

Visual cue

|

Data element

|

Action

|

Response

|

|

Blue text

|

More

|

Click

|

Adds another block of data to the content of the guide.

|

|

Resource title

|

Mouse over

|

Opens a popup preview of the resource text starting at the applicable text.

|

|

Click

|

Opens the resource to the start of the applicable text.

|

|

Right click

|

Opens the Context Menu.

|

|

Drag and drop

|

Opens the resource to the start of the applicable text at the location selected by the user.

|

|

Text comparison tool link

|

Mouse over

|

Opens a tooltip describing the action as “Show Text Comparison”

|

|

Click

|

Opens Text Comparison tool to the given passage for the resources listed in the clicked link. (1)

|

|

Right click

|

Opens a Context Menu

|

|

Drag and drop

|

Opens Text Comparison tool to the given passage for the resources listed in the clicked link as a location selected by the user. (1)

|

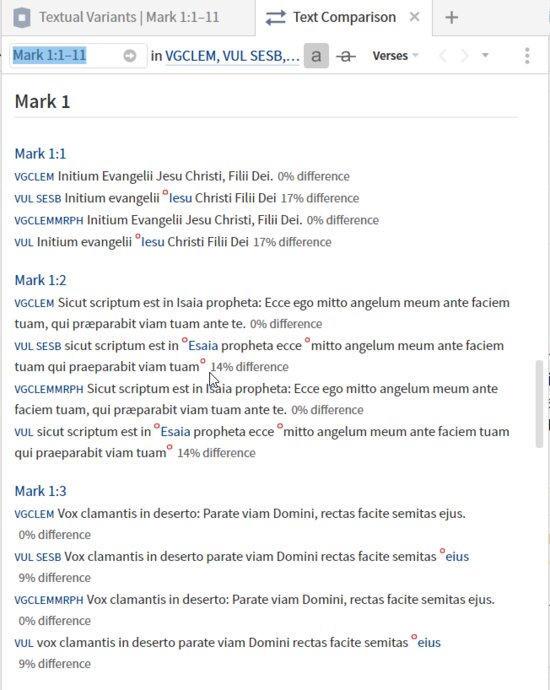

(1) Text comparison tool

Search

An equivalent search cannot be built because there is no way to specify the collection used by the application.

Supplemental materials

The Text Comparison tool augments this section which is why the guide provides a direct link to it.

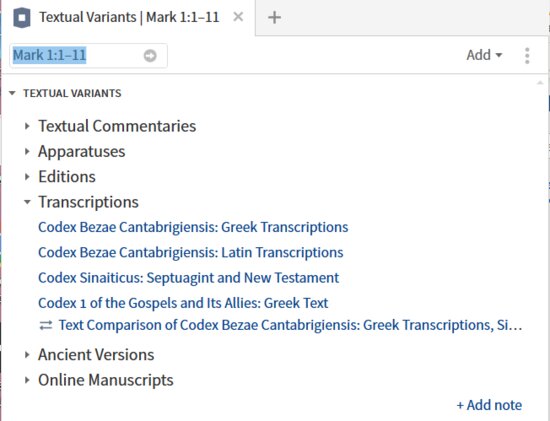

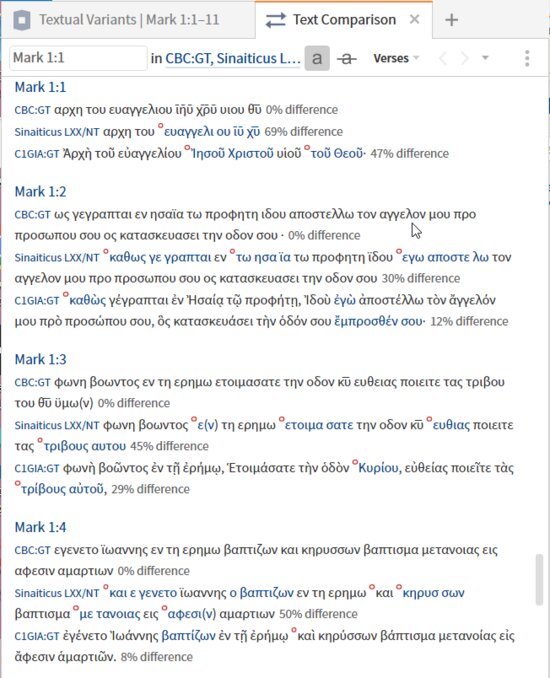

Transcriptions

Principles:[quote]

Transcriptional Principles

1. Prefer the more difficult reading (the lectio difficilior) as original. The principle of determining the reading that best explains the existence of the others comes into play here. Because scribes were interested in smoothing out the text and having it be as clear as possible, the textual critic should generally prefer the more difficult reading as the original text.63 The most puzzling reading for us was likely the most puzzling reading for the scribe and hence prompted the scribe to change the wording (for example, Matt. 5:22, in which some variants seek to soften Jesus’s difficult words by inserting “without cause” after “whoever hates his brother”). However, there are points at which a reading is too difficult (such as when one variant ending to the parable of the two sons in Matt. 21:29–31 identifies the son who promised to work in the vineyard but then didn’t as the one who did his father’s will). Then the exegete should reject the hardest reading.

2. Prefer the shorter reading. Scribes tended to add to the text, in order to clarify, rather than to delete material, especially when they believed they were dealing with God’s Word. While a transcriptional error may have led to the omission of a phrase because of mistakes such as homoeoteleuton (Greek for “similar ending,” meaning that a scribe accidentally skipped from a letter or word to the same letter or word farther down the page, leaving out material in between), the addition of explanatory material by the scribe occurs more frequently.64 By far the most common examples are references to Jesus that attract one or more titles to themselves, such as “the Lord Jesus,” “Jesus Christ,” and “the Lord Jesus Christ.”65 Preference for the shorter reading should be disregarded, however, where the context and other variants indicate that a shorter reading has occurred because a textual difficulty has been smoothed over by a scribe who decided to omit rather than include or change the difficult phrase (see John 3:13 for a good example). Additionally, certain early papyri tend to abbreviate rather than expand.66 Above all things, remember that we are seeking the reading that best explains the presence of the other variants.

Intrinsic Principles

1. Prefer the reading that most easily fits with the author’s style and vocabulary. As mentioned earlier, a reading reflecting an abrupt change in style from the author’s typical form of expression should generally be rejected if other, good readings exist.67 The longer ending of Mark is an excellent example of longer, more awkward sentences that do not much resemble the simple, straightforward Greek of the rest of the Gospel.

2. Prefer the reading that best fits in the context and in the author’s overall theological and narrative framework. If the theology appears different from what is encountered in the rest of the book, it may be the handiwork of a scribe who was interested in promoting certain theological convictions.68 The rest of the exegetical process must be considered here too. For example, literary analysis would be supremely important in a decision of this sort, in order to determine the author’s flow of thought (see chap. 4). Not only does textual criticism inform exegesis, but also proper exegesis will help determine difficult text-critical decisions, so that no one part of the interpretive process can become the exegete’s sole focus.

A highly controversial example involves 1 Corinthians 14:34–35. Because in a handful of manuscripts these verses on women being silent in the churches appear at the end of the chapter (after vv. 39–40), some scholars have argued that they may not have been written by Paul at all. After all, Paul clearly envisions women praying and prophesying in church in 11:5, even while insisting that they respect their husbands with culturally appropriate head coverings. However, the seemingly disruptive location of these verses, in the middle of Paul’s discourse on tongues and prophecy, more than adequately explains why some scribes would move them to just after Paul had finished that discussion, and there are no known manuscripts in which the verses are actually absent. As for the apparent disruption of the narrative, that may in fact be the exegetical key to their interpretation—that a much more circumscribed form of speaking is in view.69

3. Where parallel passages with variants exist (such as in the Gospels), prefer the less-harmonious reading. The scribes were more likely to harmonize seemingly discrepant parallels than to introduce new problems into their texts.70 The various authors of Scripture, however, should be granted the right to express themselves in their own characteristic fashion. In the later exegetical step of biblical theology (see chap. 9), the interpreter can determine how seemingly discordant passages can be reconciled, but that is not the task of a scribe or copyist. So when a large number of manuscripts add to the shorter, Lukan version of the Lord’s prayer in Luke 11:2 “your will be done, on earth as it is in heaven,” it is clearly to bring the prayer in line with the Matthean or more common liturgical form (Matt. 6:10).[1]

Source of errors:[quote]

2.3.2.a Transcriptional Probability

Although the scribes of biblical manuscripts were, for the most part, well trained and cautious, they were human, and humans make mistakes. The task of the textual critic is determining when copyists made mistakes and identifying those mistakes. Each of these unintentional changes has been discussed and illustrated above (see “Errors and Changes in Transmission”). A simple review is as follows:

• Haplography: Writing something once instead of twice

• Parablepsis: “Eye-skipping” that overlooks and eliminates text

• Dittography: Writing something twice instead of once

• Conflation or Doublets: Combining multiple readings

• Glosses: Adding marginal notes into the text

• Metathesis: Switching the order of letters or words

• Mistaken letters: Confusing one letter for a similar-looking letter

• Homophony: Confusing words that sound alike[2]

Prerequisite reading: none

Resources included from my library:

- The Text of the Earliest New Testament Greek Manuscripts series

- Papyrus Oxyrhynchus X 1230 et. al. from A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Revelation of St. John

- The Book of Isaiah according to the Septuagint (Codex Alexandrinus), Volume 2 (Greek Text)

- The Original Hebrew of a Portion of Ecclesiasticus: Hebrew Text

- The Beginnings of Christianity, Part I: The Acts of the Apostles, Vol. III: The Text of Acts: Codex Bezae et. al.

- Codex Bezae Cantabrigiensis: Greek Transcriptions

- Codex Bezae Cantabrigiensis: Latin Transcriptions

- Codex Sinaiticus: Septuagint and New Testament

- Biblical Dead Sea Scrolls series

- Codex 1 of the Gospels and Its Allies: Greek Text

Notice this list includes some rather large series. It does not, however, include transcriptions of fragments from journal articles e.g. Martin G. Abegg, Jr. “Messianic Hope and 4Q285: A Reassessment.” Journal of Biblical Literature 113 (1994).

Contents

The contents of the Textual variants – editions subsection is simple:

- List of resources matching the passage criteria

- More to display additional entries

- A link for a prebuilt text comparison for the major editions

Note there is no documentation on how the editions specified in the text comparison are selected

Interactions on data

|

Visual cue

|

Data element

|

Action

|

Response

|

|

Blue text

|

More

|

Click

|

Adds another block of data to the content of the guide.

|

|

Resource title

|

Mouse over

|

Opens a popup preview of the resource text starting at the applicable text.

|

|

Click

|

Opens the resource to the start of the applicable text.

|

|

Right click

|

Opens the Context Menu.

|

|

Drag and drop

|

Opens the resource to the start of the applicable text at the location selected by the user.

|

|

Text comparison tool link

|

Mouse over

|

Opens a tooltip describing the action as “Show Text Comparison”

|

|

Click

|

Opens Text Comparison tool to the given passage for the resources listed in the clicked link. (1)

|

|

Right click

|

Opens a Context Menu

|

|

Drag and drop

|

Opens Text Comparison tool to the given passage for the resources listed in the clicked link as a location selected by the user. (1)

|

(1) Text comparison tool

Search

An equivalent search cannot be built because there is no way to specify the collection used by the application.

Supplemental materials

The Text Comparison tool augments this section which is why the guide provides a direct link to it.

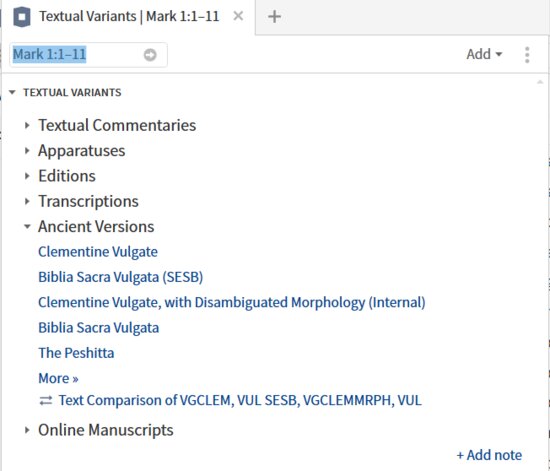

Ancient Versions

Versions of the New Testament (skypoint.com) provides a nice overview of what the contents of this section should include for the New Testament.

Bruce M. Metzger notes in Important Early Translations of the Bible:[quote]

However, by the year A.D. 600 the four Gospels had been translated into only eight of these languages. These were Latin and Gothic in the West, and Syriac, Coptic, Armenian, Georgian, Ethiopic, and Sogdian in the East.

I would suggest that Armenian has readily available texts and has a growing body of translations of related texts; therefore, it should be the next of the eight languages to be included in Verbum. A bit of bibliography to whet your appetite:

Prerequisite reading: none

Resources included (from my library):

- Clementine Vulgate

- Septuaginta: Morphologically Tagged Edition

- The Old Testament in Greek according to the Septuagint

- Göttingen Septuagint

- Septuaginta: SESB Edition (Alternate Texts)

- Biblia Sacra Vulgata (SESB)

- Clementine Vulgate, with Disambiguated Morphology (Internal)

- Biblia Sacra Vulgata

- Biblia Sacra Vulgata: Psalmi iuxta Hebraicum et Varia Lectio (SESB)

- Vulgate: Psalms Translated from the Hebrew and Variant Reading

- The Peshitta

- Old Syrian Gospels: Codex Curetonianus

- Old Syrian Gospels: Codex Sinaiticus

- CAL Targums

- Old Latin Fragment of 1 John Quoted by Augustine from a Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Johannine Epistles

- Old Latin Fragment of 3 John from Codex Bezae in a Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Johannine Epistles

- Fleury Palimpsest of 1 John from a Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Johannine Epistles

- Freisingen Fragment of 1 John from a Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Johannine Epistles

- Sahidica: The New Testament according to the Sahidic Coptic Text

- The Old Syriac Gospels, Syriac text

- Bohairica: The New Testament according to the Bohairic Coptic Text

- The Hebrew Text of Ben Sira: Text

- The Original Hebrew of a Portion of Ecclesiasticus: Syriac Text

- The Book of Jonah in Four Semitic Versions: Chaldee

- The Book of Jonah in Four Semitic Versions: Syriac

- The Septuagint Version: Greek

- The Original Hebrew of a Portion of Ecclesiasticus: Greek Text

- The Lexham Greek-English Interlinear Septuagint (Alternate Texts): Rahlfs Edition

- The Coptic Versions of the Minor Prophets: A Contribution to the Study of the Septuagint

- The Lexham Greek-English Interlinear Septuagint: H.B. Swete Edition (Alternate Texts)

- Nova Vulgata Bibliorum Sacrorum Editio

- Leiden Peshitta

- The Original Hebrew of a Portion of Ecclesiasticus: Vetus Latina

- The Hebrew Text, and a Latin Version, of the Book of Solomon, Called Ecclesiastes: Latin Text

- The Roman Psalter

Note: Verbum lacks the Vetus Latina, another essential text. Gothic is absent which has been reported as an error

Contents

The contents of the Textual variants – editions subsection is simple:

- List of resources matching the passage criteria

- More to display additional entries

- A link for a prebuilt text comparison for the major editions

Note there is no documentation on how the editions specified in the text comparison are selected.

Interactions on data

|

Visual cue

|

Data element

|

Action

|

Response

|

|

Blue text

|

More

|

Click

|

Adds another block of data to the content of the guide.

|

|

Resource title

|

Mouse over

|

Opens a popup preview of the resource text starting at the applicable text.

|

|

Click

|

Opens the resource to the start of the applicable text.

|

|

Right click

|

Opens the Context Menu.

|

|

Drag and drop

|

Opens the resource to the start of the applicable text at the location selected by the user.

|

|

Text comparison tool link

|

Mouse over

|

Opens a tooltip describing the action as “Show Text Comparison”

|

|

Click

|

Opens Text Comparison tool to the given passage for the resources listed in the clicked link. (1)

|

|

Right click

|

Opens a Context Menu

|

|

Drag and drop

|

Opens Text Comparison tool to the given passage for the resources listed in the clicked link as a location selected by the user. (1)

|

(1) Text comparison tool

Search

An equivalent search cannot be built because there is no way to specify the collection used by the application.

Supplemental materials

The Text Comparison tool augments this section which is why the guide provides a direct link to it.

63 Metzger and Ehrman, Text of the New Testament, 302–3; Wegner, Student’s Guide to Textual Criticism, 247.

64 Other frequent mistakes that will aid the textual critic in assessing transcriptional probabilities are (1) faulty word division, since there were no breaks in the early texts; (2) haplography—writing a letter or word once where it appeared twice in the text being copied; (3) dittography—writing a letter or word twice where it appeared only once in the previous copy; (4) metathesis—changing the order of words or letters; and (5) itacism—writing the wrong vowel letter that sounds like another, such as replacing an omicron with an omega. For examples of places where such errors occur in the New Testament text, see Black, New Testament Textual Criticism, 59–60.

65 See esp. Bart D. Ehrman, The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture: The Effect of Early Christological Controversies on the Text of the New Testament (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1993).

66 See the thorough demonstration of this tendency for six early papyri in Royse, Scribal Habits in Early Greek New Testament Papyri.

67 Metzger and Ehrman, Text of the New Testament, 313–14.

68 Black, New Testament Textual Criticism, 36.

69 The two most likely options are the evaluation of prophecy (a complementarian argument) or interruptions by uneducated women (an egalitarian argument). See further Craig L. Blomberg, “Neither Hierarchicalist nor Egalitarian: Gender Roles in Paul,” in Paul and His Theology, ed. Stanley E. Porter (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2006), 304–5.

70 Metzger and Ehrman, Text of the New Testament, 314.

[1] Craig L. Blomberg and Jennifer Foutz Markley, A Handbook of New Testament Exegesis (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2010), 21–24.

textual critic A scholar who examines variants in the biblical text to determine the most authentic readings.

[2] Wendy Widder, Textual Criticism, ed. Douglas Mangum, Lexham Methods Series (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2013), 36–37.