Yes, there's quite a bit of original latin from the Fathers, Perseus, etc. And unique Vulgate interlinears (the only 4-way language comparison; hebrew-latin-greek-english).

What there isn't:

- Any resources that 'in-depth' discuss the latin associated with the Bible (early latin versions, and Jerome's Vulgate amalgam). Yes, there's bits and pieces all over the place.

- Resources that discuss the translational issues.

Now, of course, I sped off to Amazon to see what I could get. No luck. That's hard to believe, given latin as a base for the largest Christian tradition. Maybe I'm blind (maybe, not maybe!).

Now, I DO have Metzger's 'Early Versions of the New Testament' which Logos doesn't offer. Granted Metzger's somewhat of an unknown.  EVNT goes into quite a bit of depth on the latin (along with the other languages as well).

EVNT goes into quite a bit of depth on the latin (along with the other languages as well).

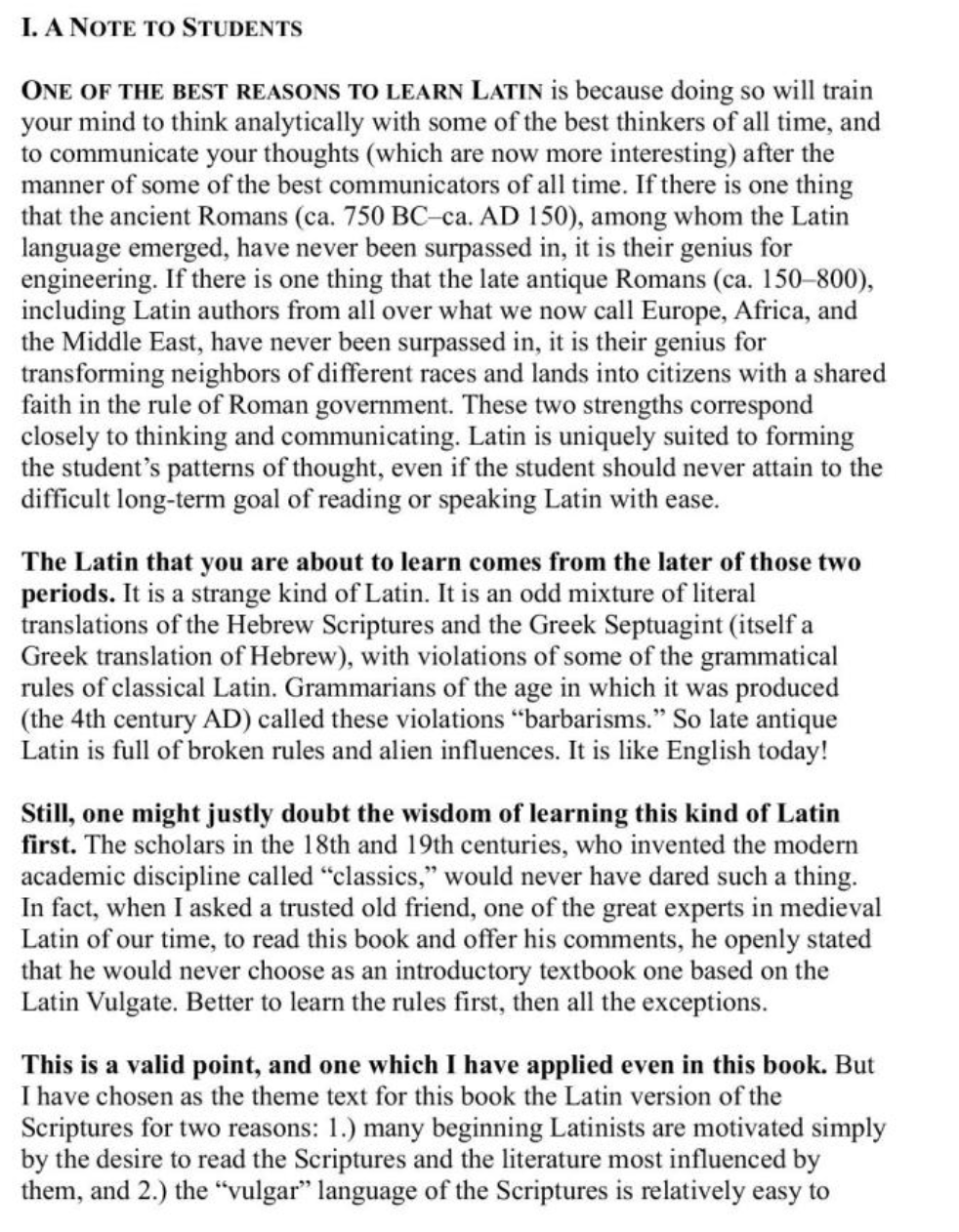

But to illustrate, I pulled the intro below from 'Jerome's Introduction to Latin' (2021!), illustrating the issue quite well .... how, exactly does a latin translation create 'meaning' visa viz the Bible (weaknesses, etc):

https://www.amazon.com/Jeromes-Introduction-Latin-Lionel-Yaceczko/dp/B09DN1631T

One of the best reasons to learn Latin is because doing so will train your mind to think analytically with some of the best thinkers of all time, and to communicate your thoughts (which are now more interesting) after the manner of some of the best communicators of all time. If there is one thing that the ancient Romans (ca. 750 BC–ca. AD 150), among whom the Latin language emerged, have never been surpassed in, it is their genius for engineering. If there is one thing that the late antique Romans (ca. 150–800), including Latin authors from all over what we now call Europe, Africa, and the Middle East, have never been surpassed in, it is their genius for transforming neighbors of different races and lands into citizens with a shared faith in the rule of Roman government. These two strengths correspond closely to thinking and communicating. Latin is uniquely suited to forming the student’s patterns of thought, even if the student should never attain to the difficult long-term goal of reading or speaking Latin with ease.

The Latin that you are about to learn comes from the later of those two periods. It is a strange kind of Latin. It is an odd mixture of literal translations of the Hebrew Scriptures and the Greek Septuagint (itself a Greek translation of Hebrew), with violations of some of the grammatical rules of classical Latin. Grammarians of the age in which it was produced (the 4th century AD) called these violations “barbarisms.” So late antique Latin is full of broken rules and alien influences. It is like English today!

Still, one might justly doubt the wisdom of learning this kind of Latin first. The scholars in the 18th and 19th centuries, who invented the modern academic discipline called “classics,” would never have dared such a thing. In fact, when I asked a trusted old friend, one of the great experts in medieval Latin of our time, to read this book and offer his comments, he openly stated that he would never choose as an introductory textbook one based on the Latin Vulgate. Better to learn the rules first, then all the exceptions.

This is a valid point, and one which I have applied even in this book. But I have chosen as the theme text for this book the Latin version of the Scriptures for two reasons: 1.) many beginning Latinists are motivated simply by the desire to read the Scriptures and the literature most influenced by them, and 2.) the “vulgar” language of the Scriptures is relatively easy to understand when compared to the polished prose of Classical Latin (“vulgar” simply means “common”). It was written for a barely-literate audience, and that is what we are when we begin to learn a new language.