Given the number of places for error in Bible interpretation:

- incorrect reading of manuscript

- incorrect assignment of ambiguous morphology

- incorrect meaning of word

- incorrect interpretation of grammar of phrase

- incorrect interpretation of syntax

- incorrect assignment of rhetorical force

- incorrect interpretation of semantics

- incorrect interpretation of pragmatics

- incorrect interpretation of semiotics

- incorrect assignment of underlying assumptions

- duplicate all the above if working from a translation

- incorrect jumps from human understanding to divine Truth

the chance that you, I or anyone is correct 100% of the time is less than a centillion (long-form) to 1. Therefore, it is a good rule of thumb that if you never change your position, clarify or revise it, your Bible study is ineffective. You are engaging in an exercise of confirming your prejudices. So how does one develop a habit of allowing your Bible study to be productive. Logos resources actually provide the tools for you to do so.

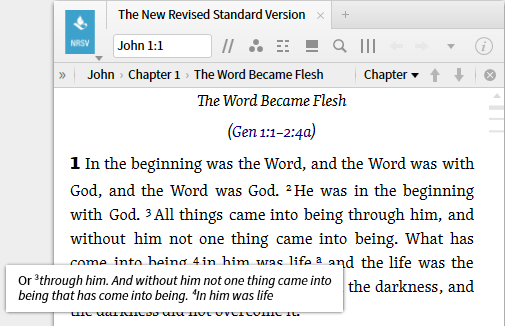

Step 1: Find an issue that the experts still disagree on. The footnotes in your Bible will give you some examples:

or the Lexham Bible Guides provides information on issues:

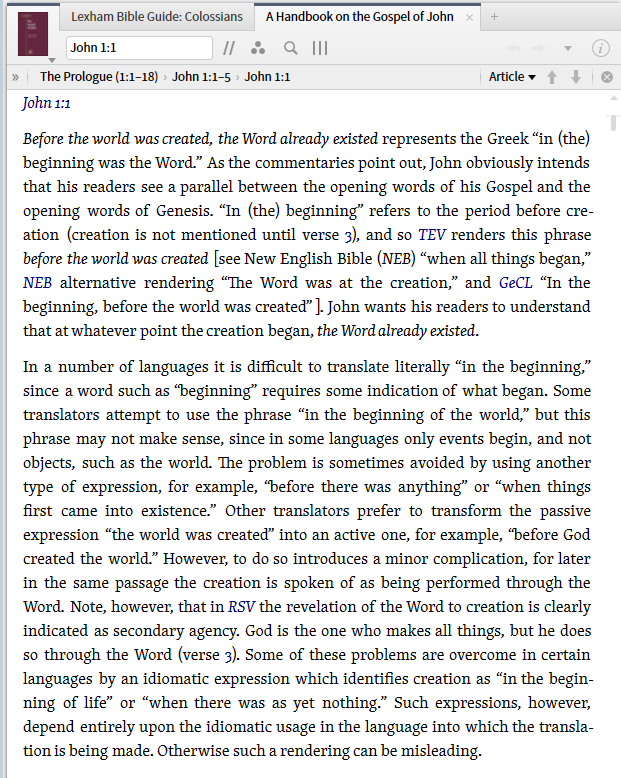

or the UBS handbook series while focused on translation problems often points out interesting issues:

Other commentaries, historical interpretations from the Church Fathers, theological interpretations etc. document difficulties you can find in the Passage Guide.

Step 2: Define the alternative positions making columns for assumptions, pros and cons for each position.

Step 3: Identify your position - it is often simply accepting your favorite translation, your favorite author, what you have been taught without really thinking about it.

Step 4: Identify the following for positions other than your own:

- if you accepted this position, would it change your beliefs?

- if you accepted this position, would it change how you worship?

- if you accepted this position, would it change how you behave?

If you are not used to being brutally honest in observing your own thoughts and assumptions, I would suggest that if you answer yes to any of these three questions, you pick a different issue. Why? Because until you get comfortable watching your own thoughts, evaluating them as you would anyone else's and actually changing your position, it is easier to practice on things that don't matter. It is very easy to be blind in those areas where change would have a significant cost.

Step 5: Ideally, having a study partner who will argue one position while you argue another in an informal dialogue argument is the easiest way to practice. And studying for the debate should provide the information needed to fill out the chart you built in Step 2. However, most of the time we are stuck using our Logos resources to fill out the chart without the motivation and feedback provided by a partner.

Step 6: When you believe that you understand the pros and cons of all the alternatives, determine which position you think has the strongest case. You should be able to claim that your study did one of the following:

- strengthened your arguments for your position

- clarified your position

- modified your position

- changed your position

A reasonable mix of the four indicates a healthy, effective Bible study.